by Thomas Fernandes

This series began with the desire to share a more diverse and lifelike account of biodiversity than the more mediatized utilitarian framing used in reporting, awareness campaigns, or pleas for conservation. This position is far from unique; the philosopher Arne Naess articulated the deep ecology movement more than 30 years ago, in which the first two principles are:

- The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves. These inherent values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.

- Richness and diversity of life-forms are also values in themselves.

Valuing life for its own sake is something few would oppose in principle. Yet the reality of this value is tested only when choices must be made, at which points commitment to abstract principles often dissolves first. But these principles don’t have to remain abstract. Writing these essays made me care more about biodiversity than when I started. Not through moral argument, but through familiarity. Learning about vultures did more to make me care about their extinction than any reasonable arguments. Closeness came from spending time in their world, not from being told they matter. It is hard to care for the alien.

Yet valuing life for its sake does not mean it does not have value for us. Yes, ecological value, but also in enabling a change in perspective. We get stuck in perceptual ruts so deep we cannot imagine alternatives. We assume our way of seeing is simply how things are.

This is the core of Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory of Perception, in which he challenges the idea that perception reconstructs the objective properties of the world as they really are. Instead, he argues that perception actively constructs the perceptual world of an organism. What we experience are not faithful renderings of reality, but species-specific solutions shaped by evolution.

According to the Interface Theory of Perception, an organism’s perceptions function as a user interface between that organism and the objective world. Hoffman’s preferred analogy is the computer desktop. The icons, folders, and trash bin we see are not representations of the underlying reality of the machine. They conceal it. Beneath them lies an incomprehensible complexity of circuits and voltages. The icon is useful precisely because it hides this reality, presenting only what matters for action.

This becomes immediately apparent when we consider other organisms. To a bee, flowers don’t look like they do to us. Pollinators operate with different interfaces altogether, attuned to smells and UV colors that largely escape us. The same understanding of an alien mind is what brings both care and insight.

To repurpose an SSC observation: “Sitting in an armchair and trying to think of the most shockingly different extraterrestrials you can imagine still gets you something more humanoid and less alien than simply adopting a spider’s perspective for the purpose.” This is exactly what Adrian Tchaikovsky did in his series Children of Time, if you are interested.

Hoffman offers a striking example in the Australian beetle Julodimorpha bakewelli. Male beetles search for mates using simple rules where shiny, dimpled, brown objects signal receptive females. For millennia this worked. Then humans arrived, and so did empty beer bottles along roadsides. The bottles matched every mate cue perfectly, shinier and browner than any female beetles. Males abandoned actual females to court bottles instead, a recipe for extinction on its own, made even worse by the presence of predatory ants in the discarded bottle.

The point is not littering, but how easily we recognize the failure in other species’ perceptual systems while remaining blind to our own. Yet, even in others, failures draw our attention while success hides its own intricacy and efficiency. And so, the risk remains that we only understand the limitations but not the perspective.

In a previous essay I mentioned that insect vision was shifted toward UV but could not see red. Upon reading this, we most easily imagine seeing objects in different colors in an otherwise unchanged vision space. Similarly, you probably imagine the flight experience of a bee in a way that you would experience it in a flight simulator. But how does the bee really perceive its flight and its situation in space?

Contrary to intuition, smaller animals do not see finer detail. Visual acuity depends on the ability of an eye’s optics to project two distinct points in the world onto distinct receptors. A human eye, roughly 17 mm in size, projects an image 85 times larger than a 0.2 mm insect eye. Assuming similar receptor sizes, this alone limits insects to far coarser spatial resolution.

Depth perception is even more constrained. Reconstructing depth from binocular comparison (difference between left and right eyes) requires widely spaced eyes that insects cannot have due to their size. Reconstructing depth from the level of lens adjustment for the image to resolve on the retina is also impossible because of how small the adjustments are in smaller eyes.

Under these size constraints, evolution favored visual systems that use other strategies for guiding behavior and locomotion. Compound eyes can be understood as the solution to effectively provide those inputs. Rather than approximating a blurred version of vertebrate vision, the system is organized around a different priority: motion detection.

Compound eyes are not just faceted-looking eyes. Each facet, called ommatidia, is effectively its own eye, with its own lens and its own retina producing its own neural input. Here each facet functions less like a camera than like a directional pixel. The image resolution projected onto an individual facet’s retina is of little relevance; the facet’s role is primarily to register whether light is present and, if present, the light’s intensity and spectral characteristics. Together, the thousands of ommatidia create a mosaic of motion and brightness across a 360° visual field, rather than the overlapping high-resolution images produced by human eyes.

Because each facet is permanently assigned to a specific angle in the visual field, motion can be directly encoded as a pattern of changing activation across neighboring facets. When an object moves, it sweeps from one facet’s range to the next, immediately specifying direction and angular displacement without requiring complex image reconstruction. This system makes motion detection faster and more reliable by reducing the need for internal neural computation but it cannot detect depth from a static image.

To try to bridge this alien world perception, let’s move away from anatomical description to observations from studies on visual motor computations in insects.

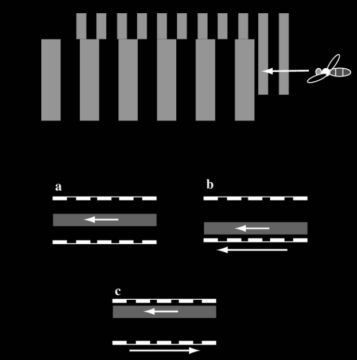

Without depth perception, how would you fly straight through a tunnel? Bees rely on motion, in particular the angular velocity their visual system is built to notice. To maintain a straight path, a bee simply needs to track wall features and make sure the wall “moves” as fast on both sides. You don’t get it? A bee would take it for granted.

Imagine driving on a highway. Now, notice how nearby road markings blur past quickly, while distant mountains appear almost static. The apparent speed of objects depends not only on how fast you move, but on how close they are. This is called parallax.

Now imagine that there are regularly spaced lamp posts on each side of the road. At constant speed, lamp posts closer to you will pass you by faster than those on the other side of the road. Making sure both sides appear to move similarly would put you right in the middle of the highway (do not attempt this experiment). This is exactly what the bees are doing. They do not measure distance to walls; they equalize image motion which we can also call optic flow.

Experiments confirm this using moving patterns on walls to create an optical illusion for bees. When patterns on one tunnel wall are moved artificially in a direction opposing bee flight, the patterns appear to be moving faster for the bee. To equilibrate optic flows, the bee then moves away from that wall.

Because the perception of relative motion depends on both speed and distance, a bee cannot easily distinguish between the two. However, since landmarks are typically static, this ambiguity rarely poses a problem. In fact, it is this very ambiguity that allows the bee to use a single visual cue, optic flow, to simplify its flight control.

To maintain a steady velocity, bees attempt to keep the rate of retinal image displacement constant, much like ensuring lamp posts pass by at a regular pace. Setting up an illusion to confirm this, experimenters constructed a tunnel of varying width. When the walls get closer it makes the features appear to pass faster on both sides. In response the insect believes it is now flying faster and slows down to try to maintain a constant speed.

Despite being susceptible to experimenters’ manipulations, bees’ visual systems are very efficient. In a natural environment, insects can maintain a seamless “autopilot”, ensuring flight navigation in complex environments with minimal processing of a single visual cue.

By minimizing image motion within a specific visual window in the direction they want to go the insect effectively freezes a portion of its world to steer toward. Maintaining constant optic flow on both sides allows it to navigate obstacles as needed. And since it cannot gauge distance directly it will use the already monitored optic flow to estimate it.

To test this distance estimation, researchers trained bees to fly through a narrow 6-meter tunnel to reach a feeder. The close proximity of patterned walls created an intense optic flow, tricking the bees into overestimating their travel distance.

To estimate how far the bees thought they had flown, scientists decoded the waggle dances of returning bees. The waggle dance is the way bees communicate foraging opportunities to one another (discussed here). I find it amazing that we grasp some insect communication well enough to get a sense of how they perceived their journey by the way they talk to each other about it.

As predicted, the bees signaled a flight of 200 meters, well above the actual distance. This confirms that image motion, rather than physical effort, is the dominant cue to gauge how far they have traveled. Remarkably, this is only false information from our perception. Because all bees perceive motion the same way, a recruited bee following the 200-meter signal would find the information accurate. While the narrow tunnel exaggerated the objective distance traveled, the communication remained true as directions to follow.

This “autopilot” steering method is so efficient that it also naturally solves what seems the most complex part of flight, landing.

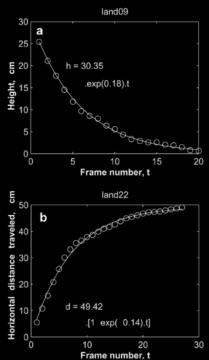

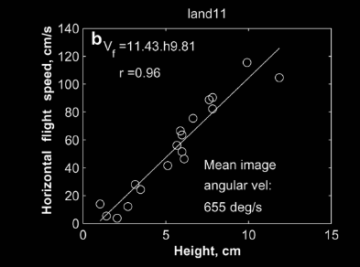

In our view, managing a successful landing requires the complex juggling of lowering speed as you reduce height and get closer to the landing zone. Precisely what cannot be done on autopilot. Figure 3 illustrates a successful landing in human notions of depth (height) and speed. This landing requires synchronizing two complex curves.

For a bee, just like in Figure 2, as a surface gets closer it will slow down proportionally to maintain constant image motion. This is all that is needed to ensure a smooth landing. To illustrate, Figure 4 represents the same maneuver, plots the exact same points, only from an insect perspective. Maintaining a constant apparent image velocity solves the problem of adjusting approach speed to height.

So, is optic flow the only cue? No. Insects have many more senses than vision for once. Also even limiting ourselves to vision, we know bees recognize colors and patterns and are able to learn from them, including using simple counting and arithmetic abilities. Optic flow is only the main navigational clue with relative size. If an object seems to increase in size rapidly it means it is getting nearer and nearer. Yet without depth perception the clue is vague and relative size is used mostly to avoid imminent collisions during flight.

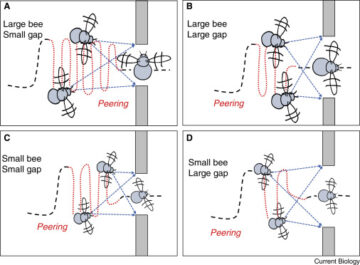

When looking for precise spatial estimation insects must construct them through sensorimotor loops. By this I mean that they move and oscillate their bodies to generate cues from various angles and obtain a better representation of their space. Those data-gathering maneuvers are known as peering flights. This is illustrated below, with an experiment on bumblebees.

When encountering narrow gaps, bumblebees peering flights patterns become more frequent and sustained. Interestingly, larger bees invest more time in this behavior than smaller ones, highlighting a need for spatial precision tailored to their body size. This also demonstrates an estimate of their own body size with respect to the openings. Depending on what their estimations are bees will then go through the opening sideway if needed, like you would in narrow openings.

Flies’ seemingly erratic flight pattern in enclosed spaces can probably be understood as peering flight. A data gathering exercise embodied in movement. Similarly, bees fooled in previous experiments by various wall widths can be understood as them being in autopilot mode. Using peering flights, they are well able to reconstruct complex image of their surrounding and precisely estimate distances as shown here by the bumblebees.

Why expend effort when a low-cost strategy works? What appears as a lack of ability may instead reflect energy conservation. In this study of bees’ counting abilities, discrimination improved only when errors were punished with bitter solutions. When rewarded with sugar alone, bees simply chose at chance, deciding not to invest energy.

Here, we have tried to familiarize ourselves with a different view than ours, how it both responds to bees’ behavioral need and how behavior is in turn adapted to the visual systems. The next essay will build on this to explain other insect behaviors and what the “rules of the hunt” look like from the perspective of the most efficient hunter of the animal kingdom: The dragonfly.

***

For readers interested in turning this lens back on ourselves, I’ve written a functional analysis of human color perception here

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.