by Christopher Hall

“The essence of repression lies simply in turning something away, and keeping it at a distance, from the conscious.” –Freud, “Repression”

“Time and again, in conversation with friends, some of who have lost family members in this killing spree, there is a sense that one must be going mad: to see so plainly the destruction, the murdered children filmed and presented for the world to look upon and then to hear the leaders of virtually every Western nation contend that this is not happening, that whatever is happening is good and righteous and should continue and that in fact the well-being of the Palestinian people demands this continue – it’s enough to feel like you’re losing your mind.” –Omar El Akkad, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This

The characters in Kasuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go are living in the midst of an atrocity, but they certainly don’t act like it. They go through their lives in much the way we expect characters to do in realist novels; there’s fallings in love and out of it, slight and major misunderstandings, a bit of sex here and there, etc. But the jarring difference (spoiler ahead) is that the main characters are all clones, and their destiny is to have their organs harvested until the point that they “complete” – die, in other words. This is not, it is to be emphasised, a novel of resistance. It is a story about people immersed in a system which treats them reasonably well until the time comes to fulfill a purpose which will mean their destruction. In tone and plot, Ishiguro’s work is not really much different from a Thomas Hardy novel; the characters are locked within a social structure which is crushing them and will eventually destroy them, but from which they can see no means of escape. But if we shake our heads at the confines of 19th century social standards in one instance, that becomes (or at least it did my case) a yelp of rage once we come to Ishiguro’s heartbreaking conclusion. Do something! It’s right there and it’s wrong, don’t you see it? I shouted at the characters. Fight back! Protest! Run Away! But this is nonsense; the characters, and everyone else they encounter, clone or not, are caught within the matrix of “It’s just the way it is” and, as of course it is implied, so are we.

The triad of victim, perpetrator, and bystander presents itself oddly in Ishiguro’s novel, and the boundaries of each begin to blur. The protagonists are unquestionably victims, but their general stasis also presents them as near bystanders. They seem unable to adopt the cognitive tools necessary to escape their plight. They see, but do not see, the atrocity all around them. The perpetrators are, for the most part, distant entities, and themselves can play the role of the bystanders – they participate in a system they might disagree with, and perhaps try to mitigate its worst effects – but they participate all the same. Ishiguro does not seem to be making an overt political point here, but the sense of inevitability and helplessness everywhere in the novel, again as in a Hardy novel, either fills one with existential dread or a level of hope for some kind of speculative redemption.

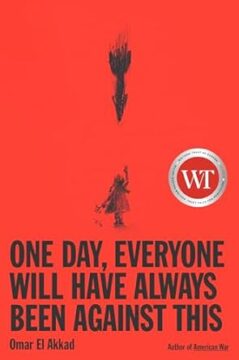

I’ve had Ishiguro’s novel on my mind as I’ve been making my way through Omar El Akkad’s National Book Award-winning One Day, Everyone Will Have Have Been Against This. El Akkad, born in Egypt, emigrated to Canada in the 1990’s and currently lives in the States. A journalist, he’s been a war correspondent in Afghanistan and has investigated Gitmo. He has published two novels, the first of which (American War) is about a Second Civil War overtaking America. One Day is a non-fiction work that interposes events from his life with reflections on the coverage in the West of the most recent Israel-Palestine conflict. It is a book of rage and disappointment – how can, he repeatedly asks, liberal societies so constantly fail to live up to their ideals when it comes to “foreign” conflicts, especially the Israel-Palestine one? Why did the West so consistently fail to act, or even to do something so basic as to call things what they are, when it became clear that what was happening in Gaza was a genocide?

El Akkad has a number of answers for this question, but what I’m going to discuss here is not necessarily the source of this willful ignorance, but rather its cost for us perpetrator/bystanders, of this seeing but not seeing. Yes, some atrocities go on in places the West barely acknowledges as actually existing – one is going on in Darfur as we speak. But the genocide of the Palestinians does not have the same status. It is, just about, right there. It may be not occurring outside my window, and it may be the case that I’ve never been through such horror, don’t share a racial or religious identity with the victims, have never been the Middle East, etc. – none of that becomes particularly relevant when an atrocity is as well-documented and disseminated as this one is. For everyone in the West, the Palestinian genocide and its aftermath are now part of the air we breathe – they are “the way it is.” And whether we cheer it or deplore it, our states and societies decided as it was ongoing that there wasn’t much they were going to do about it.

Freud’s theory of repression was focused on sexual mores, but I do think there is a broader ethical mechanism that works similarly to it. Unless we are committed to being a terrible person (and to be sure many people are), morality, like sexual desire, imposes an imperative on us that demands some kind of response – and will not be discharged if we simply look away. So, if our answer to the question “Ought we to bomb children?” is anything other than irrevocably negative, something has gone significantly wrong, and perhaps the real task of ethics ought to be to focus on the phenomenological experience of ignoring the obvious – because many people are, tacitly and sometimes overtly, answering “yes, it is” when it comes time to consider whether dropping bombs on the heads of children is justified for any reason. There is, I think, a kind of psychic engineering behind this kind of moral avoidance. The atrocity, of course, has a level of distance if we are not actively participating in it – if we’re not the ones doing the mutilating and the murdering. But individual action is not really at the core of the issue here. The problem is not really that people fail to do the right thing when that thing is obvious, either because they are fallible or genuinely evil, but rather that, as a collective, we consistently fail to demand the right thing be done on larger scales. The demand for action that moral obviousness entails collapses at the level of the group. And the reason is not difficult to discern – groups entail paralysis. Thus bystander and perpetrator dissolve into one another, become inextricably mixed.

But even if consensus culture supposedly privileges no single viewpoint, the truth cannot be batted away; it is like the rock Samuel Johnson kicked to disprove Berekleyian idealism. The dissonance created when we absorb moral truths without confronting them is a key source of modern democratic dysfunction, to my mind. To keep breathing, we tread in the blood of others. But that’s too much; it can’t be blood, must be something else, something innocuous – maybe it’s just water after all. This might not be saying much that’s new, but here’s the key: once you’ve decided that you can see something for what it isn’t, you give yourself permission see other things in the same way.

Repression is a reflex, and the more it’s practiced, the easier it becomes to do. It’s perfectly obvious to me, for example, that the overabundance of guns and the ease with which they can be acquired has a direct relationship with the high number of gun deaths in the United States. More importantly, I think this is in fact obvious to everybody, even the most ardent supporter of the Second Amendment. But once you’ve decided that more guns do not equal more gun deaths (or that it doesn’t matter because your freedom to own a gun is more important than the lives of others), any other sort of mental disjunction becomes less of a burden on the mind and soul. Moral repression grants a kind of freedom – the same freedom you feel in littering when there’s trash everywhere. But the freedom is illusory – you are instead bound into moral framework in which cries for justice become so heavily distorted that they begin to sound like “Give us more of what is destroying us.” Repression inverts and redraws the picture of reality. Whatever ethical imperative used to be staring you in the face has now altered and subtly moved behind you, pushing you to become more comfortable with barbarity.

And so dissonances cluster; the imperial boomerang also can’t be far from our minds. If Israel has been a kind of test kitchen for the new hybrid form of autocratic rule that’s emerging in the West, it has done so precisely on the back of the work done by this kind of psychic engineering. Where full democracy is undesirable, but still valued, compromises can be made; this new crop of authoritarians seems most eager to use the tropes of democracy as a legitimizing force. So the burden of treating every one of our fellow citizens with some degree of equity is banished from consciousness; simply, to some we will grant the full measure of civil rights, to others less, and to some none at all. There are those we protect, and those we have permission to destroy or watch destroyed. Democracy and its institutions are permissible only to the point they cease to be dysfunctional; you have all the civil rights you could ask for until an ICE agent decides you don’t. The atrocities which then become inevitable are close, but also distanced. They are right there, but we give ourselves permission to be bystanders at the same time we are perpetrators. Those who have accepted that this is a just way of arranging things must “put away” what they see and adopt some new, insidious way of moving forward. When J D Vance tells us we did not see what we saw when Renee Good was murdered, he is building on the permission his administration tacitly and overtly gave us to ignore the mass murder of Palestinians – and, of course, all of the other instances when the American state decided that some people simply weren’t good enough to merit continued existence.

All of this depends on my belief, which I cannot in any way justify, that some things are just morally obvious, and that there is a mechanism within just about every human mind which knows evil when it sees it. (That, of course, is assuming a lot, but it has the advantage that I can remain fundamentally an optimist even while I think humanity is likely doomed.) A notion like this, I think, lies at the core of the somewhat tortured verb tense of the title of El Akkad’s book. The future perfect conditional implies a kind of retroactive continuity, a sudden revelation that reveals the truth about what was “really” going on. The truth was always there, but we missed the signals somehow. So are moral truths eternal, and can they be “hidden” and then “discovered?” That’s a question asked many times, and which may be too obtuse for the current purpose – and again, do we, did we ever, really need to “discover” the right answer to the question about dropping bombs on children?

At any rate, even if we could all be much, much more aggressive in our processes of reality testing, it’s perhaps too much to say this puts us on the path to mental health. El Akkad is hardly alone in worrying that he’s losing his mind. I suppose the conclusion of what I have to say here is that there are good ways and bad ways to do so – the madness of those who have seen and will not turn away has at least something of better value than the pervasive genteel delusion.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.