by Chris Horner

There are many great authors of the past who have survived centuries of oblivion and neglect, but it is still an open question whether they will be able to survive an entertaining version of what they have to say. —Hannah Arendt

A book should be an ice axe for the frozen sea within us. —Franz Kafka

…for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life. —Rainer Maria Rilke

Here’s a view I’ve heard or read many times: art is entertainment, its purpose is to provide pleasure and diversion. I think this is mainly wrong. While it contains a grain of truth, it overlooks the profound ways in which art can challenge and transform us. Art’s value lies beyond pleasure, in its capacity to question who we are and what we do. It may even say to us that we must change our lives.

Fun

Entertainment, at its core, is about diversion and pleasure. Fun. It occupies our attention, distracts us from boredom, and amuses. But many things in life can do that: food, games, conversation, idle distractions. If we define art solely as entertainment, we risk conflating it with any activity that gives pleasure, and end up with nothing distinctive about art. After all, I like to eat ice cream, have a hot shower, go for a walk and listen to Mozart. I enjoy all those things, but I’ve surely missed something about the specificity of the experiences if I just call them all just pleasure. That approach is ‘utilitarian flattening’: everything is about pleasure, and so anything one does is just for that goal: art as a tool for pleasure, a means to an end, a pleasant way to pass the time.

Passing the time: diverting, distracting: that entertainment? But passing the time isn’t always pleasurable. Anyone who has scrolled on their smart phone or flipped through videos on YouTube knows that diversion can be form of bored unpleasure, a way to pass time that leaves us emptier than when we started. If Art is to be entertaining it had better do more than that.

Troubled Pleasures

Genuine pleasure is something we often get from art. But when it does please us, this is often not because we directly aim at it, but rather as a side effect. Some art can initially baffle and challenge us, but it excites and prompts our curiosity. So, pleasure is mingled here with something else –effort, or attention. And ‘pleasure’ itself isn’t just a brute given, something we switch on or off, or gets triggered randomly. To take pleasure in art – whatever the genre or complexity of it – is something we learn. It is an effect of socialisation and Bildung, the self-development of the person as she grows in a specific time and place.

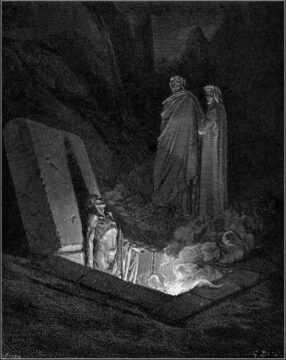

And some art that we value doesn’t give pleasure at all, and that, too, is something we can come to appreciate, to even look for. There are plenty of examples of art which does something other than please. Some art conveys horror and misery: Picasso’s Guernica, for instance, or Goyas’ Disasters of War. We might admire the craftsmanship, the formal qualities and so on, and call that a kind of pleasure, but there would be something odd if we stood back and just smiled in satisfaction at what is being depicted. The same thing goes, surely, for the experience of reading All Quiet on the Western Front or The Grapes of Wrath: readerly pleasure is there, but so is something else. What else?

A Way of Knowing

Art is a kind of tool for knowing ourselves and our world. Visual art, literature, and theatre can reveal aspects of our inner lives, our cultures, and our histories that are not accessible through entertainment alone. Shakespeare’s plays, for instance, delve into the depths of ambition, love, jealousy, and betrayal, offering insights into the human condition that remain relevant centuries later. Slow paced films like Tarkovsky’s Stalker do not merely entertain but explore themes of desire, morality, taboo and the sacred in ways that may transform us, if we let them. Through them we can discover who we are or might become.

It is a way of discovering who we are, and we will not always like what we find there. Exploring the complexities of human experience can mean grappling with ambiguity and confronting uncomfortable truths. In this sense, art is akin to philosophy or psychoanalysis, a way of probing the depths of existence, not just a means of passing time. And it can perform this service in ways unavailable to other modes of enquiry or contemplation. A novel or a poem can explore something that it might be well-nigh impossible to put in propositional form. Consider coming across this is in a novel or short story: ‘she had thought she loved him but realised now that she did not’. It reflects the kind of complex experience that we can have in our lives and offers ways in which we can follow how this might be possible. The character is fiction, the experience universal. Another example: William Blake’s The Sick Rose, which says more about possessive love in two short stanzas than a thousand pages of prose could do.

Transcendence

Art has historically served many roles beyond entertainment. In different cultures and eras, art has been intertwined with religion, philosophy, and the pursuit of truth. Medieval cathedrals were designed not just to impress but to elevate the spirit and connect worshippers with the divine; ancient Greek tragedies explored the complexities of fate, justice, and human suffering. Art’s roots in the religious lives of our forebears is perhaps a clue to what it can mean for us now: a form of transcendence, a way of confronting the void, the sublime, the mysterious (music seems particularly suited to this). For the flaw in the utilitarian claim about art lies in its misunderstanding about what we are. We are not just pleasure-seeking monads. We have powerful drives that push us, and push art, in Freud’s formulation, ‘beyond the pleasure principle’. It is surely not just there to be another kind of fun.

One of the most compelling arguments for art’s deeper significance is its capacity to help us know ourselves. Art challenges us, provokes thought, and invites reflection. Music, for example, can move us emotionally and intellectually, prompting us to confront feelings and ideas we might otherwise ignore. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with its “Ode to Joy,” is not just entertaining, it is a celebration of human unity and aspiration. Joyce’s Ulysses, which can be a tough read, takes us through styles of writing, types of degradation , beauty and ugliness in the banal, sexual longing and much more– the list is huge. ‘Enjoy’ the book, or not, you won’t be quite the same if you read it.

The idea that art is “just entertainment” is a relatively modern one, shaped by consumer culture and commodification. If we allow ourselves to reduce art to just that, we mutilate it, as some movie adaptations do to ‘classic’ novels – Arendt’s remark about entertaining versions of art is on point here. But most of us seek more than diversion. We want to be moved, challenged, and changed. We want art to help us make sense of the world and our place in it. Entertainment can be part of this, but it is not the whole story. it can also educate, provoke, heal, and transform. It is a means of knowing, of revealing the hidden. A way of engaging with the deepest questions of existence, of exploring what it means to be human. Art can ask us hard questions about ourselves, and the experience being interrogated can be uncomfortable. But that discomfort is central to the human condition and the idea that it isn’t part of what we are and what we seek is a shallow one. Art can demand that we change ourselves. Whether we rise to that challenge is another matter.

More on what art can do here.