by Sherman J. Clark

Is your uncle racist? Is the American educational system? Are military beard standards? Is our president? I won’t try to answer those questions here. I don’t even know your uncle. Instead, I want to talk about what we mean when we use that term—and the confusion we experience as a result of the ways we use it. This won’t solve our underlying problems having to do with race; but it might help us address those problems more clearly.

The terms “racist” and “racism” appear daily in our political debates, social media, and institutional communications. They shape hiring decisions, educational curricula, and corporate policies. They can end careers, transform elections, and rupture communities. Yet for all their prominence—or perhaps because of it—we rarely pause to notice that we use these words in fundamentally different ways.

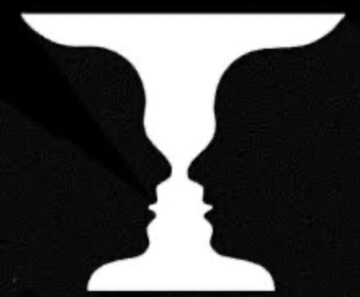

This semantic multiplicity creates dysfunction. We believe we are engaged in substantive disagreements about race and justice when we are often simply talking past one another. One person declares a policy racist, meaning it produces disparate outcomes; another hears an accusation of malicious intent and responds defensively. One person insists they are not racist, meaning they bear no personal animus; another hears a denial of systemic advantage and reacts with frustration. The confusion compounds: accusations of racism are met with accusations of bad faith, which generate accusations of fragility, which prompt accusations of ideological extremism. The cycle accelerates, positions harden, and the possibility of genuine exchange evaporates.

Before attempting to map these different uses, let me address two predictable responses. First, many readers—particularly those working in antiracist traditions—will argue that there is in fact a correct definition of racism: not simply individual animus but structural oppression, grounded in history and enforced through institutions of power. This is indeed an important definition, one with considerable analytical power. But my purpose here is not to adjudicate which definition is correct. It is to observe that people use the word in various ways, and that we cannot by mere insistence make everyone adopt the definition we prefer. If we want to communicate effectively, we must reckon with how our words are likely to be heard, not just how we intend them.

Second, I am not naive about the strategic deployment of definitions. Some uses of “racist”—and some objections to its use—are manifestly disingenuous. People shift definitions opportunistically, to score points or avoid responsibility. Greater clarity will not eliminate such maneuvers. But it may help us identify when they are at work and distinguish genuine misunderstanding from rhetorical manipulation.

What do we mean?

For many Americans, calling someone racist is primarily a judgment about their interior life—what they think, feel, or believe. Within this broad category, we can identify at least four distinct uses.

Hatred or hostility. In this most visceral sense, a racist harbors active antipathy toward members of another racial group. Racism here is animus—conscious, often proud, sometimes violent. The Ku Klux Klan is racist in this sense, as are those who openly advocate for exclusion or violence against people of color. This definition has the virtue of clarity: it identifies racism with conscious malevolence. But this very clarity becomes a limitation when racism-as-hatred becomes the only definition someone recognizes. If racism requires burning crosses or using slurs, then anything short of that standard seems like an unfair accusation.

Prejudiced beliefs. A second use identifies racism not with emotion but with cognition: the belief that members of certain racial groups are inherently inferior in intelligence, morality, industriousness, or other qualities. These beliefs need not manifest as hatred. They may be expressed matter-of-factly, even regretfully—“I wish it weren’t true, but…” This definition captures something the first misses: that calm stereotyping can be as damaging as passionate hatred.

Unequal concern. A third variant locates racism neither in hatred nor in belief but in care—or its absence. A racist, on this view, is someone whose empathy is racially bounded, who feels less urgency when harm befalls members of certain groups. This definition illuminates phenomena the others might miss: the person who abhors violence but somehow always finds reasons why this particular police shooting was justified, who supports humanitarian aid in principle but grows impatient when racial disparities are mentioned.

Race-consciousness itself. Some extend the term to encompass any racial distinction-making at all. On this view, noticing race, categorizing by race, or organizing around racial identity constitutes racism. Sometimes this usage is transparently tactical, as when opponents of affirmative action claim such policies are “the real racism.” But not always. Some genuinely believe that racial categories themselves are the problem—that a truly just society would be colorblind.

The proliferation of definitions within just this one category—racism as mental state—already suggests why our conversations so often derail. When one person says “that’s racist,” meaning “that reflects unconscious bias,” and another hears “you’re filled with hatred,” we’re not having a disagreement but a miscommunication.

All these uses treat racism as fundamentally a property of minds. But a second major category shifts focus from interior states to external arrangements—from what people think or feel to how systems operate and outcomes distribute.

Institutional and structural disadvantage. In this usage, “racist” describes policies, practices, or institutions that generate racially disparate outcomes regardless of intent. School funding tied to property taxes, lending algorithms that incorporate zip codes, sentencing guidelines that treat crack and powder cocaine differently—all might be called racist in this sense. The sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva writes of “racism without racists,” capturing how inequality persists through apparently neutral mechanisms.

Systemic oppression and power. A more comprehensive usage treats racism not as symmetric prejudice but as a historically rooted system of domination. On this account, racism equals prejudice plus power. Individual bias against white people might exist, but without institutional backing, it doesn’t constitute racism. This framework explains persistent inequalities that attitude-based definitions cannot. But it also creates semantic friction: “Black people can’t be racist” makes perfect sense within a power-based framework but sounds absurd to someone using racism to mean prejudice.

Cultural and epistemic dimensions. Still other uses examine how racism operates through knowledge systems and cultural frameworks. George Lipsitz describes a “possessive investment in whiteness”—the accumulated advantages that come from being seen as normal, default, unmarked. Charles Mills writes of an “epistemology of ignorance”—the systematic not-knowing that allows racial privilege to remain invisible to those who benefit from it.

What are we doing?

The inherent ambiguity of the term racist is only part of what makes conversations challenging, because parsing definitions gets at only a small part of what is happening in racial discourse. When someone calls a person, policy, or institution “racist,” they are rarely engaged in neutral description. They are performing a speech act with purposes that extend well beyond conveying information or making arguments.

Some of these purposes are entirely legitimate. Calling something racist can communicate moral reprobation—marking conduct as beyond the pale of acceptable behavior. It can unmask hidden motives or effects, revealing dynamics that might otherwise remain invisible. It can rally solidarity, calling people to collective recognition and action. It can shock listeners into awareness, breaking through comfortable ignorance that gentler language cannot penetrate. It can invoke historical weight, connecting present arrangements to past injustices. And it can simply express pain or outrage—which needs no further justification.

Other deployments are more problematic. The word can be used to create false equivalences—“anti-white racism is just as bad”—that obscure actual power differentials. It can dismiss concerns without engagement, functioning as a conversation-ending weapon rather than an invitation to understanding. It can foreclose inquiry through accusation, making it impossible for the accused to respond without seeming defensive. And it enables strategic definition-shifting: invoking structural definitions when attacking opponents’ policies while retreating to attitudinal definitions when defending one’s own.

This matters because the choice of whether to use the word “racist”—and which definition to invoke—is often less about accuracy than about what we’re trying to accomplish. The same conduct might be described as “reflecting unconscious bias,” “perpetuating structural inequality,” or “racist,” and each framing does different rhetorical work. The first invites reflection; the second calls for systemic analysis; the third delivers a punch.

And sometimes a punch is exactly what is needed. There are moments when what is called for is not careful analysis but confrontation—when someone must be made to feel, not just understand, the weight of harm they’ve been able to ignore. The person insulated from racial harm may need to be made uncomfortable before they can become truly engaged. In such moments, the electric charge of “racist”—its capacity to accuse, to discomfort, to demand response—serves important purposes that measured academic language cannot.

Rhetorical Phronesis

What, then, does it mean to navigate this complexity skillfully? The goal cannot be to establish a single, universally accepted definition. That won’t work. Nor should we pretend that definitional clarity is always the highest value. What we need is what Aristotle called phronesis—practical wisdom—applied to our racial discourse: the capacity to recognize which definition is operative in a given context, to understand what purposes are being served, and to discern when precision helps and when it hinders.

This starts with definitional awareness—learning to hear not just words but the frameworks that give them meaning. When a corporate diversity officer speaks of “racist structures,” she likely means something different from what a rural voter means by “I’m not racist.” Developing this awareness means attending to subtle cues: professional context, generational markers, educational background, regional variation.

It extends to what we might call semantic translation—the capacity to move between definitional frameworks while signaling the movement. “When you say racist, do you mean…?” becomes a tool for clarity rather than confrontation. “I’m using racist in the structural sense, meaning…” becomes a way to prevent misunderstanding before it occurs. This doesn’t mean abandoning your own understanding, but being able to build bridges between frameworks.

And it includes discernment about purposes—recognizing when someone is trying to communicate information, express moral judgment, rally support, or simply wound. The appropriate response to each differs. Meeting a genuine attempt to communicate with definitional questions can be clarifying. Meeting an expression of pain with definitional questions can be cruel. This all also involves recognizing when definition itself is beside the point—when what is needed is not precision but power, not clarity but confrontation. The skilled practitioner knows both how to cool a conversation down for careful analysis and how to let it stay hot for moral urgency.

What might this look like in practice? Sometimes it might mean beginning important conversations with what we might call definitional humility: “I want to be clear about how I’m using ‘racist’ here…” Sometimes it might mean developing greater tolerance for what seems like hypocrisy but might actually be definitional confusion—when someone simultaneously claims not to be racist while supporting policies that perpetuate racial inequality, they might be operating with different definitions for different purposes, perhaps without realizing it. And it might mean recognizing that insisting on our preferred definition, however analytically powerful we believe it to be, is sometimes counterproductive. Meeting people within their definitional framework, then gradually expanding it, can in some situations be more effective than demanding they adopt our usage before conversation can begin. Again, this does not mean naively assuming that people are always speaking in good faith. It means hearing them, and helping them hear you.

The goal is not to make “racist” mean one thing. Language does not work like that. And the R word in particular does too much work—historical, analytical, moral, political—to be confined to a single definition. The goal is to develop the practical wisdom to navigate its multiple meanings and purposes: to know when precision serves and when it stifles, to recognize which definition is operative and why it matters, to discern what the speaker is trying to accomplish.

This is demanding work, requiring patience, humility, and considerable emotional regulation. It requires us to sit with discomfort, to resist the satisfying clarity of our preferred definitions, to genuinely try to understand why others need these words to mean what they mean to them. Moreover, the weight of this work does not fall fairly. Those out of power often face the cruel necessity of understanding and rhetorical phronesis—not because it is always deserved, but because it is necessary to communication and persuasion. Victims of racism in its various forms too often face the double pain of having to understand and communicate with those who themselves should be doing the work of understanding. But in a democracy that must somehow reckon with its racial past and present, developing this capacity isn’t optional. It’s part of what it means to be citizens together, struggling toward justice with the imperfect language we have.