by S. Abbas Raza and ChatGPT 5.1

S. Abbas Raza: You may have heard of John Brockman who is a well-known American literary agent and author specializing in scientific literature. Brockman led a scientific salon for 20 years, asking an annual question to a host of scientists, philosophers, and other thinkers, and publishing their answers in book form. For the last such book, instead of asking for answers to a question, he requested that the contributors each submit one question to which they would like to know the answer, and the resulting list of questions was once again published as a book in 2018 entitled The Last Unknowns with a foreword by Daniel Kahneman. Here is the question that I submitted and was published in that book:

S. Abbas Raza: You may have heard of John Brockman who is a well-known American literary agent and author specializing in scientific literature. Brockman led a scientific salon for 20 years, asking an annual question to a host of scientists, philosophers, and other thinkers, and publishing their answers in book form. For the last such book, instead of asking for answers to a question, he requested that the contributors each submit one question to which they would like to know the answer, and the resulting list of questions was once again published as a book in 2018 entitled The Last Unknowns with a foreword by Daniel Kahneman. Here is the question that I submitted and was published in that book:

Why is sleep so necessary?

The questions were simply printed in the book with the author’s name, one to a page, without any commentary or explanation but let me give a short explicatory comment here. Much of my curiosity about sleep had to do with the word “so” in my question and the work it is doing there. One reads many accounts of what happens when we sleep. For example, the flushing of toxins from the brain, cellular repair, etc., but what I found unsatisfying was that none of these seemed to me to give good reasons we necessarily have to be unconscious for the process to take place. And the advantage one would gain from not having to be asleep for a very significant portion of one’s life would clearly be so profound that if there were any easy way evolution could have found a way around sleep, over hundreds of millions of years of reproducing different kinds of brains, it would have. But we see that any animal with a brain, no matter how tiny or complex, from fruit flies to humans, needs to sleep. That is why I asked why sleep is “so necessary”, because I suspected that the answer to that question would tell us something very fundamental about the design of the brain.

A couple of days ago, I mentioned to my wife, Margit, that a few months after GPT3 was released to the public by OpenAI at the end of November in 2022, months that I spent intensively learning about how transformer models like ChatGPT work (transformer is the “T” in GPT and a particular architecture of artificial neural networks), it suddenly occurred to me that AI models may have provided us with the conceptual vocabulary to more easily understand what is happening in the brain when we sleep. I then went on to explain to her what I meant in the following way:

Human brains are not “pre-trained” with data the way a large language model (an LLM like ChatGPT) or other types of deep-learning AIs are. Instead, the synaptic weights throughout our “thinking brain”, probably the neocortex at least, are adjusted according to our experiences throughout our life. But while we know what an artificial neural network’s learning algorithm is during pre-training (it’s called “backpropagation“), we know that in our case it is not backpropagation, but we also do not know exactly what the learning algorithm (which goes and adjusts the synaptic weights) for human brains is.

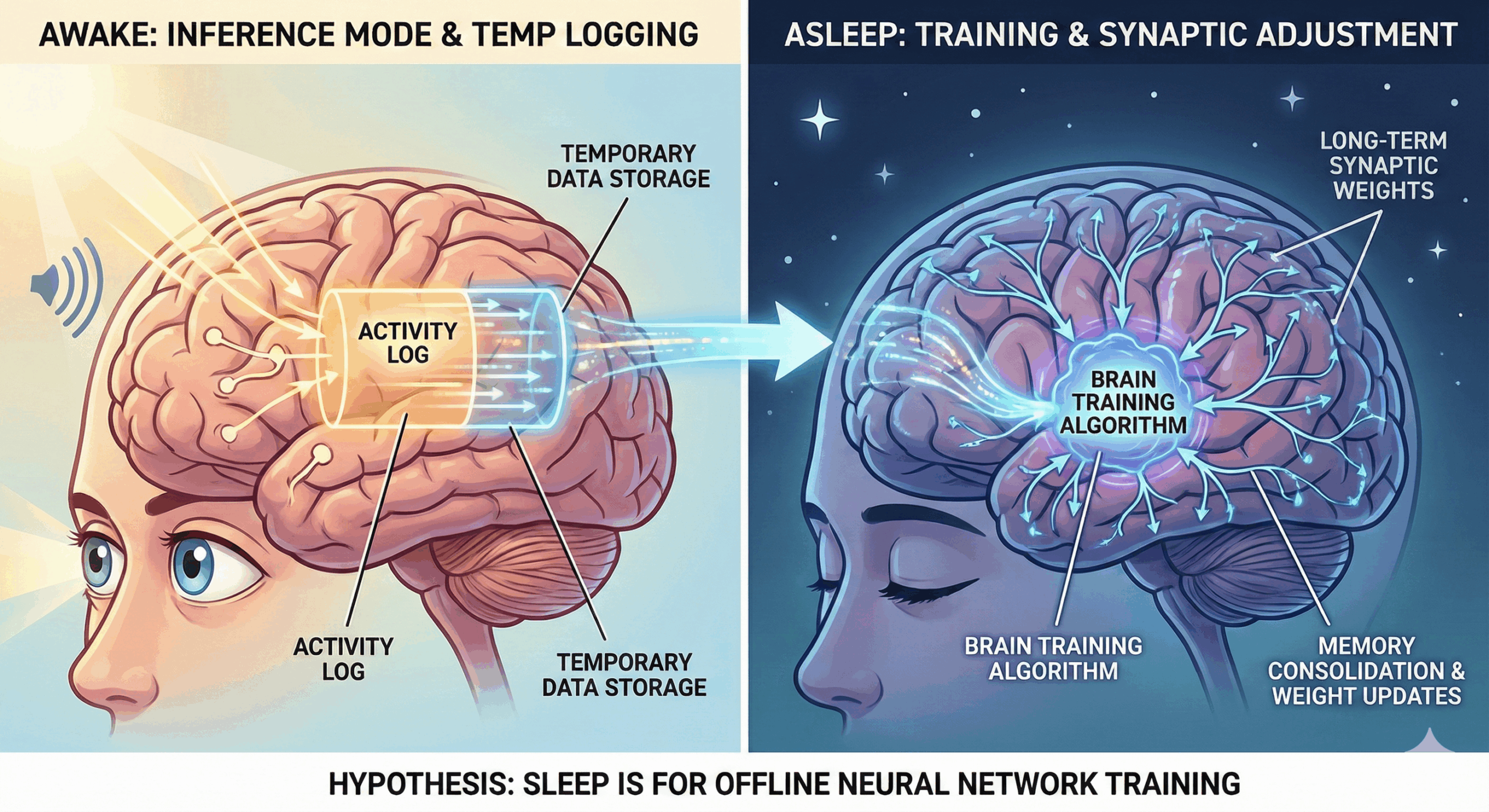

Now it seems plausible (even likely) to me that every day while we are awake, we are in a kind of “inference mode” where the brain is responding to stimuli just the way an LLM responds to “prompts”: by running the incoming signal through a neural network which then outputs an action, sometimes in the form of speech, sometimes in ways like other types of motor commands, for example. I suspect that all such activity is also stored in some temporary memory (as an LLM might save the memory of an extended chat with me without changing any of its own synaptic weights), possibly in the hippocampus (I know just enough neuroscience to suspect this), without any synaptic weights elsewhere in the brain getting permanently adjusted. Then, when we sleep, this “activity log” is used as data to run the training algorithm of the brain (like the “pre-training” of an LLM) which then somehow propagates through the thinking part of the brain (again, probably mainly the neocortex) adjusting synaptic weights and incorporating the experiences of the day into long term synaptic memory. The reason we must be asleep for this to happen is that we cannot safely and reliably be running the neural network as an inference engine while this adjustment of synaptic weights is going on. Doing that would result in continuous hallucinations or worse.

Margit then told me I should write an explanatory article about this on 3QD and I responded that I would have to do a lot of research in areas of neuroscience in which I am no expert, and I am not sure I have the ability or the time to do that. But later (while I was falling asleep, as it happens!) it occurred to me that the LLMs have now become so good at research that I can try to simply have them look into this for me. And so I explained what I have just explained to you above to ChatGPT (5.1, thinking/deep research mode) and then asked:

I want you to do two main things for me: 1) Search for research on this topic and see what you can find, and 2) Look into and propose the detailed mechanism of how and where (what parts of the brain) the human brain might be storing what I have called its “activity log” each day, before it is then used to “train” the brain while we sleep, based on evidence from neuroscience. Please also consider subcortical structures, foundational older studies, and animal models that might shed light on mechanisms applicable to humans. Thank you!

ChatGPT then took exactly 10 minutes to do the research and answer my questions. I was already familiar with some of what it told me but much was also new to me. Its answer below is long but quite interesting (at least to me). Very short version: It seems that my intuition is quite plausible, at least. Oh, and in the interest of readability, I have removed the many and long citations from each paragraph below, but can provide them to anyone who wants them.

ChatGPT: This is a fascinating and rich line of inquiry, Abbas. I’ll dig into neuroscience research related to your idea that the brain may operate in an ‘inference mode’ during waking hours, storing daily experience in a temporary ‘activity log,’ and then switches to a ‘training mode’ during sleep, adjusting synaptic weights across the neocortex and subcortical structures. I’ll look at both recent and foundational research, and include relevant animal studies that can inform human brain function.

Sleep and Synaptic Memory Consolidation: Why the Brain Needs “Offline” Time

Evolutionary Necessity of Sleep for Brain Function

Sleep is a universal and essential behavior across virtually all animal species. No known complex animal has evolved to eliminate sleep entirely – even dolphins and certain birds only cheat by sleeping one brain hemisphere at a time to remain partially alert. The fact that animals risk vulnerability while unconscious suggests that sleep serves a critical, non-negotiable function. Indeed, experiments show that depriving creatures of sleep impairs cognition, and we spend about one-third of our lives in this offline state. This implies that whatever happens during sleep is so fundamental that evolution favored “turning off” conscious awareness despite the obvious survival drawbacks.

One well-supported function of sleep is brain maintenance at both cellular and network levels. For example, during sleep the brain’s “glymphatic” system dramatically increases fluid exchange, flushing out metabolic waste products like β-amyloid that build up during wakefulness. Natural sleep (or deep anesthesia) enlarges the space between brain cells by ~60%, allowing cerebrospinal fluid to wash through brain tissue and clear toxins much more effectively than during waking. This nightly “cleanup” helps restore metabolic homeostasis and is thought to protect neurons from damage. However, purely metabolic explanations (e.g. toxin removal) don’t fully explain why consciousness must be turned off – in principle, one might imagine cleaning the brain while still awake. The deeper reason for an offline state appears to lie in how neural circuits learn and reorganize, as discussed next.

Sleep as “Offline Training” for the Brain’s Neural Networks

A leading theory in neuroscience is that sleep is when the brain performs vital memory processing and synaptic adjustments, analogous to running a training algorithm on the day’s accumulated data. During wakefulness, our brains mainly operate in “inference mode,” responding to stimuli and generating behaviors (much like an AI model responding to prompts). The day’s experiences – new facts, events, skills, and stimuli – induce activity in neural circuits and produce temporary memory traces. While some synaptic changes occur during wake (forming initial, labile memories), the brain largely holds these experiences in short-term storage until it can consolidate them later. In other words, the brain maintains an “activity log” of what happened – patterns of neural firing and preliminary synaptic modifications – but doesn’t fully commit all these changes to long-term stable memory while we are busy interacting with the world.

Sleep provides the critical opportunity for the brain to enter “training mode” and solidify these memories by adjusting synaptic weights across neural networks. This idea echoes the Complementary Learning Systems framework proposed by McClelland, McNaughton, and O’Reilly (1995), which was influenced by earlier theories (e.g. David Marr in 1971). According to this theory, new information is quickly encoded in a temporary store (primarily the hippocampus and related structures) without immediately overwriting the neocortex’s established knowledge structures. The hippocampus can rapidly capture episodes (“fast learning”) but has limited storage, while the neocortex gradually integrates knowledge over time (“slow learning”) to build stable, generalized models. To avoid interference, the integration must be gradual and interleaved – exactly what sleep accomplishes. During sleep (especially deep non-REM sleep), the hippocampus replays recent experiences, effectively reinstating the day’s memories for the neocortex to rehearse and encode. With each replay, cortical synapses adjust a little, eventually consolidating the memory into long-term form. By morning, the memory that was initially dependent on the hippocampus becomes distributed in cortical networks (now “offline trained”), allowing the hippocampus to be freed up for new learning the next day. This process explains why damage to the hippocampus causes anterograde amnesia – new experiences cannot be stored and “trained” into cortex, even though old memories (already consolidated in cortex) remain intact.

Notably, the concept of memory consolidation during sleep has empirical roots going back at least a century. In 1924, Jenkins and Dallenbach found that people remembered nonsense syllables better after a sleep period than after an equivalent awake period, suggesting sleep stabilizes memories by preventing interference. Countless studies since then have reinforced that retention is better if a learning interval includes sleep. For example, subjects who learn a list of word-pairs or a motor sequence and then sleep on it perform significantly better (either through gains in memory or less forgetting) compared to those who stay awake. In short, sleep provides conditions for the brain to “remember to remember” – consolidating and integrating new information into the existing knowledge network.

Replay of Daily Experiences in Sleeping Brains (Evidence from Animals)

How does the brain actually carry out this nocturnal training? A remarkable body of research shows that during sleep (and quiet rest), the brain literally replays neural activity patterns from recent waking experience. This phenomenon was first discovered in rats by Wilson and McNaughton in the 1990s and has since been observed in many species and brain areas. In a classic study, rats ran a maze while researchers recorded neurons in the hippocampus (a region crucial for spatial and episodic memory). Later, during slow-wave sleep, those same neurons fired in nearly the same sequences as when the rat ran the maze – as if the rat’s brain was re-running the day’s maze journey in its sleep. Strikingly, the replay during sleep can be sped up (~10x faster than real time) and even fragmented or reversed, indicating that the brain is not merely re-playing passively but actively “editing” and processing the memory. These replay events are not just curious coincidences; they appear to serve a functional role in learning. Wilson’s lab showed that disrupting these replay events (by experimentally disturbing hippocampal activity during rest) impairs the rat’s memory for the maze. In contrast, biasing which memories get replayed (e.g. by playing associated sounds during sleep) can strengthen those memories preferentially. The brain, it seems, uses sleep as a time to “process and reconsider experience in multiple ways, chopping it up, running it in reverse, and speeding it up” to build a better model of the world.

Replay is especially well-studied in the hippocampus, but it is a widespread phenomenon involving multiple brain regions (including subcortical structures) acting in concert. For instance, in rats that learned to associate specific places with rewards, neurons in the hippocampus and in the ventral striatum (a subcortical region involved in reward and motivation) were found to reactivate together during subsequent sleep. Notably, the hippocampal “place cells” tended to fire just before the striatal “reward cells,” suggesting the hippocampus was leading or instructing the replay in downstream regions. This coordinated reactivation likely helps link the spatial memory with its emotional/reward significance, strengthening the place-reward association overnight. It aligns perfectly with the idea from consolidation theory that the hippocampus orchestrates replay to teach other parts of the brain. By replaying a complex memory (e.g. “in this location, I found food”) across the relevant networks, the brain can bind together the what-where-when aspects and store them more durably as a unified memory.

Another fascinating animal example comes from bird song learning. Juvenile songbirds (like zebra finches) learn to sing by listening to adult tutor songs and practicing their own vocalizations. During the day, a young finch’s brain is highly active as it produces and hears songs, but the real learning improvement often happens after a night’s sleep. Research by Dave & Margoliash (2000) recorded neurons in a motor area of the finch brain (analogous to a motor cortex) and found that when the bird is asleep, those neurons fire patterns that mirror the patterns seen during song practice. In fact, if you play back the bird’s own song to it during sleep, its brain activity looks much like it did when the bird was singing while awake. Even more impressive, the bird’s brain also shows “spontaneous” bursts of song-related activity during sleep – effectively the bird is rehearsing its song internally at night. These data led to a model wherein the day’s sensorimotor experience (the pairing of vocal motor commands with the heard sounds) is stored temporarily during singing but not used to alter behavior immediately, and then an off-line comparison during sleep evaluates the bird’s performance and adjusts the motor commands for next time. In plain terms, the young bird’s brain logs the errors and successes of its daytime practice and then at night “trains” on that data to gradually refine its song. By the next morning, the bird sings a bit better. This is a beautiful example of the brain using sleep to perform a form of supervised learning on the day’s experience, something very akin to what you hypothesized.

Similar replay-supported consolidation has been observed in many contexts: rodents replaying paths to navigate mazes, birds dreaming of their songs, and even during human sleep (though measured less directly). For example, human brain imaging and EEG studies show that the same cortical areas activated during learning a task tend to reactivate during subsequent sleep (especially during slow-wave sleep and sometimes REM sleep). And if that reactivation is disrupted, memory performance suffers, whereas enhancing it (e.g. via cueing learned information with odors or sounds during sleep) can improve recall. All these lines of evidence strongly support the idea that during sleep the brain is “offline” exactly because it’s busy replaying and consolidating the experiences of the day. We cannot safely continue to take in new inputs or behave normally while this internal training is going on – thus, consciousness is essentially put on hold.

Mechanisms: How Sleep Enables Synaptic Weight Adjustments

From a neuroscience perspective, sleep provides a unique cocktail of brain states and neurochemical conditions that enable synaptic remodeling. There are two main sleep phases to consider – Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep (which includes deep slow-wave sleep) and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep – and both appear to play complementary roles in the learning process.

During NREM sleep, the brain’s electrical activity is dominated by slow oscillations (around 0.5–4 Hz) – these are the high-amplitude “slow waves” seen in EEG. Neurons in the cortex oscillate between active (up) states and silent (down) states in a synchronous rhythm. Crucially, NREM sleep also features bursts of sleep spindles (brief 12–15 Hz oscillations generated by the thalamus) and hippocampal sharp-wave ripples (very fast ~100 Hz oscillations in the hippocampus). Research has revealed that these oscillations are precisely coordinated: a cortical slow-wave “up-state” (when cortical neurons fire) often coincides with a spindle, which in turn “nests” a hippocampal ripple event in its trough. In effect, the neocortex, thalamus, and hippocampus are timing their activity to communicate during NREM. The hippocampal ripple is when large ensembles of hippocampal neurons fire together – this is thought to be the physiological substrate of a memory replay event. The thalamic spindle may serve to gate sensory input and also facilitate plasticity, and the cortical up-state means the cortex is briefly receptive to input. Through this orchestrated triad (slow oscillation + spindle + ripple), “freshly encoded memories are replayed, potentiated, transformed, and eventually embedded in the neocortex for long‐term storage”. In simpler terms, the hippocampus sends out bursts of memory information (replay), and the cortex – guided by the thalamus – listens and adjusts its synapses to integrate the new information. If one disrupts any part of this cycle (for example, experimentally suppressing hippocampal ripples), the consolidation of memory is impaired.

At a molecular level, NREM sleep also creates conditions favorable for synaptic plasticity and growth (needed to solidify memories). Paradoxically, it supports both strengthening of important connections and weakening of irrelevant connections (we will elaborate on the weakening shortly). During deep NREM, there is high release of growth hormone and protein synthesis in the brain, and certain genes related to synaptic formation are upregulated. However, interestingly, many “long-term potentiation” (LTP)-related genes are actually downregulated during NREM, while genes for depotentiation (synaptic weakening) are up. This suggests that NREM may bias the brain towards synaptic renormalization – broadly scaling back synaptic strengths that were increased during wake. According to the Synaptic Homeostasis Hypothesis (SHY) put forward by Tononi & Cirelli, during a day of learning, many synapses throughout the brain get potentiated (strengthened) as we acquire new information, which increases synaptic weight overall. This growth is energetically costly and saturates the network, so the brain needs a way to “pay the price for plasticity”. Sleep, especially slow-wave sleep, is thought to be the time when the brain globally downscales synapses – a bit like normalizing or pruning the network – to prevent runaway saturation. Crucially, this downscaling is not random forgetting: it’s hypothesized to disproportionately affect the weakest or least-used connections, while preserving the relative differences that encode the important memories. By the end of sleep, the overall synaptic strength is reduced (freeing up energy and saving space for new learning), but the salient patterns (strengthened by replay) remain imprinted. In support of this, experiments in rodents and flies have found that markers of synaptic strength (like certain receptor levels or electrophysiological measures of synaptic potentiation) are higher after wake and drop after sleep. In short, NREM sleep both consolidates new memories and homeostatically fine-tunes the network, which together require an offline brain state to avoid interference with ongoing cognition.

REM sleep, on the other hand, is quite a different beast neurophysiologically. During REM (the stage when most vivid dreaming occurs), the brain’s activity becomes more similar to an awake state – EEG shows faster, low-amplitude waves, and many brain regions are active in a spontaneous, internally driven way. Neurochemically, REM is characterized by high acetylcholine and virtually zero noradrenaline in the brain. This milieu is very conducive to plasticity: for example, studies show LTP (long-term potentiation) can be induced more easily during REM than in waking. Also, genes related to synapse formation and growth tend to be upregulated in REM. In contrast to NREM, REM seems to strengthen or re-potentiate circuits, possibly especially for skills and emotional memories. Many researchers believe that REM sleep is important for integrating the freshly consolidated memories into the broader network of older memories – finding creative connections, extracting the “gist” of information, and promoting innovative insights. There’s experimental evidence for this: for instance, solving certain problems or gaining insight into hidden rules is more likely after a night of sleep, particularly if REM sleep was sufficient. A recent study (Abdou et al. 2024) in mice demonstrated that completely new inferential knowledge (figuring out relationships not explicitly learned) emerged only after a day’s delay with sleep, and not immediately after learning. By selectively inhibiting activity in the mice’s anterior cingulate cortex (a prefrontal region) during NREM or REM, the researchers showed that both stages were necessary for this off-line problem solving: NREM sleep organized the learned information into a usable schema, and REM sleep “computed” the novel inference from that organized knowledge. In other words, the idling brain was actively making new connections. This illustrates how REM sleep might take the stabilized building blocks from NREM and imaginatively recombine them, which aligns with the everyday experience that dreams often mix elements of our life in odd ways and that sometimes we wake with a new perspective on a problem.

Dreaming in REM sleep has intrigued scientists for years, and one compelling theory posits that it serves to prevent overfitting of our brain’s model of the world. The “overfitted brain hypothesis” (E. Hoel, 2021) draws an analogy to machine learning: during each day, our brain learns from a very particular dataset – our daily experiences – which might cause it to latch too specifically onto patterns of that day. To ensure we maintain the ability to generalize (and not just memorize), the brain “invents” dreams – essentially hallucinated, random or exaggerated scenarios – to provide some out-of-distribution input and noise, thereby regularizing the brain’s neural network. According to this view, dreams are like augmented training data that help the brain avoid overfitting to the day’s experiences, improving resilience and adaptability when we face new situations. While this hypothesis is still being investigated, it resonates with the notion that the brain in REM is exploring state spaces without external constraints, possibly adjusting synapses in a way that fosters robustness. Notably, REM sleep is known to preferentially consolidate procedural memories (how to do things) and emotional memories. For example, studies have shown improvements in motor skills (like a finger-tapping sequence or navigating a virtual maze) correlate with the amount of REM sleep, and depriving REM can impair such gains. REM may also help re-balance emotional circuits – it’s been proposed that re-experiencing emotional events in dreams, but without the rush of noradrenaline (the stress neurotransmitter, which is absent in REM), allows the brain to reconsolidate those memories in a calmer context, possibly explaining why “sleeping on it” can ease emotional distress.

Bringing this together, we see that different parts of sleep play different roles in the brain’s nightly training regimen. NREM provides slow, coordinated “training sessions” where new memories are repeatedly played to the cortex (with the hippocampus as the tutor) and where overall synaptic weights are renormalized to prevent overload. REM provides a highly plastic state for integration, creativity, and fine-tuning, possibly strengthening certain connections and adding variability to prevent rigidity. What they share is that in both cases the brain largely disconnects from external input and outward behavior – because it must. Running these complex internal algorithms – replaying myriad patterns, weakening some synapses, strengthening others, and even spontaneously generating dream scenarios – would be incompatible with reacting appropriately to the outside world. If the brain tried to do both at once, the interference would likely degrade both processes (imagine trying to update the wiring of a computer while it’s actively running a program – errors would abound). Thus, conscious awareness is suspended as a necessary trade-off: the “thinking brain” (especially the neocortex and hippocampus) focuses inward on optimization, while the vital autonomic functions (breathing, heartbeat, etc., controlled by subcortical and brainstem areas) continue running in the background. In essence, evolution found that it’s more efficient to have a dedicated offline period to recalibrate the neural network than to attempt continuous 24/7 learning. This is consistent with the observation that even in animals with intense lifestyles (migrating birds, or marine mammals), some form of sleep is always preserved – they may reduce or localize it, but cannot eliminate it without impairing function.

Where Is the “Activity Log” Stored? – The Role of Hippocampus and Beyond

Your intuition that the brain keeps a daily “activity log” which is then used for training is very much in line with current neuroscience, and the hippocampus is the star player in that regard. The hippocampus (with its associated structures like the entorhinal cortex) is often likened to a fast write-to-memory buffer. During an experience – say you meet someone new at a party – the neocortex is processing the sensory inputs (what they look like, sound like, etc.) and engaging in the immediate interaction (inference mode). Simultaneously, the hippocampus quickly binds together a record of this event: the sights, sounds, context, and your thoughts at that moment get linked into a neural ensemble in the hippocampus. This initial encoding happens through rapid synaptic plasticity in hippocampal circuits (it can form memories in one trial). For the rest of the day, that memory is stored in the hippocampus in a relatively short-term form. If you were asked about it later that evening, the hippocampal trace could reactivate and you’d recall the person’s name or the conversation (thus the hippocampus also serves as an index to retrieve recent memories). However, the new memory’s synaptic imprint in the cortex is still fragile at this stage – the cortex did engage during learning, but its synapses have not fully reorganized to permanently store this memory.

The “activity log” is thus distributed: the hippocampus contains a compressed index and replay script of the day’s events, and various cortical and subcortical areas contain the provisional memory traces of the experiences (for example, the auditory cortex holds some trace of the conversation, the amygdala might hold the emotional tone if it was significant, etc.). Additionally, specific patterns of neural activity from the day can be “tagged” at the synaptic level. Neuroscientists talk about things like “synaptic tagging” and immediate early gene activation – when a neuron is highly active during an experience, it can trigger certain proteins that mark those synapses as needing consolidation. These molecular tags (e.g. expression of the gene c-fos in a subset of neurons) can linger for hours. During subsequent sleep, the neurons that were heavily used during the day are more likely to reactivate (part of replay), and those tags make the synapses more receptive to lasting change (e.g. protein synthesis for strengthening). In this way, the day’s significant experiences are earmarked for consolidation.

When sleep comes, the hippocampus becomes extremely important for orchestrating memory replay. As described, in NREM sleep the hippocampus generates sharp-wave ripple events – these are essentially bursts of hippocampal neurons firing in patterns that reflect recently stored information (the “log” entries). It’s been shown in rats that those ripple events often re-play sequences of places the animal visited, in the same order or sometimes in reverse. The neocortex, which during wake was busy with perception and action, is now in a synchronized slow-wave state that opens a window for the hippocampal messages to be broadcast. The thalamus helps by producing spindles that transiently boost the communication between hippocampus and cortex, precisely timing cortical excitability to the incoming hippocampal input. The information flows through the entorhinal cortex (the gateway between hippocampus and neocortex) into cortical circuits, effectively replaying the experience to the cortex. Each replay is an opportunity for cortical synapses to adjust – if neuron A and neuron B in cortex were both activated by the experience, the replay will make them fire together again, reinforcing the connection (per Hebb’s rule “cells that fire together wire together”). Through repeated nights of such training, the cortical representation of the memory becomes stronger and more interlinked with existing knowledge networks, while the hippocampal “training signal” becomes less necessary. Experiments in humans and animals show that after a memory is fully consolidated (which can take days to weeks), the hippocampus is no longer needed to recall it – it has been “uploaded” to the cortex, so to speak. Early evidence for this was the finding that hippocampal damage causes temporally graded amnesia: recent memories (from the past day or two) are lost because they were still hippocampus-dependent, but very old memories remain (they had years to consolidate in cortex).

We should also consider other structures in the “activity log.” The hippocampus is crucial for episodic (event) and spatial memories, but what about skills and habits? Those rely on different circuits, such as the basal ganglia (striatum) and the cerebellum, as well as the motor cortex. Research indicates that these circuits also undergo off-line reactivation and plasticity during sleep. For example, as mentioned above, ventral striatum neurons in rats replay reward-related firing in sync with hippocampal replay. In motor cortex, recordings in rodents learning a new skill show that patterns of neuronal firing during training reappear in subsequent sleep (often during REM or brief NREM bouts), and disrupting this replay can impair skill retention. A 2015 study by Ramanathan et al. demonstrated that ensembles of neurons in rodent motor cortex reactivate during post-learning sleep, and this sleep-dependent reactivation in motor cortex was essential for improving a learned motor skill (e.g. running on a rotorod). Similarly, in songbirds, as we saw, the “motor program” for singing is refined in sleep through replay in the song motor pathway. These examples show that the brain’s “log” of daily experience is stored in the very circuits that were active during learning, and many of those circuits have a chance to replay and improve offline. The hippocampus often provides high-level coordination – especially for declarative memories – but other subcortical structures (like striatum for procedural tasks or amygdala for emotional memories) also participate in sleep consolidation. In humans, imaging studies have found that if you learn a skill like juggling or a sequence of finger taps, the next day’s performance improvement correlates with sleep-phase activity in regions like the motor cortex, striatum, and even the hippocampus (depending on the task), suggesting those regions underwent off-line processing during sleep.

An intriguing aspect of sleep consolidation is that it also seems to involve communication between distant regions to integrate information. For example, the hippocampus might replay a memory of you meeting that new person at the party, but to fully consolidate it, the brain may link that memory with related knowledge: perhaps your prefrontal cortex integrates the inference “that person is Alice’s cousin” from pieces of info, or your amygdala attaches an emotional valence “I felt happy meeting them.” Sleep appears to be a time when such integration happens. The study in mice (Abdou et al. 2024) we mentioned showed a dialog between the medial entorhinal cortex and anterior cingulate (prefrontal) cortex during REM sleep was able to create a new inference that the mouse hadn’t directly learned. This suggests that different parts of the cortex “talk” to each other in sleep to discover latent connections. The hippocampus (via entorhinal cortex) likely sparks reactivation of memory traces in multiple areas, and then cortical-cortical connections can form or strengthen, yielding new insights or generalized knowledge by morning.

Foundational Studies and Animal Models Shaping Our Understanding

To appreciate how strongly the scientific evidence supports your hypothesis, it’s worth highlighting some foundational findings across decades and species:

- Early memory and sleep research (1920s–1960s): The idea that sleep aids memory is old. Jenkins & Dallenbach (1924) first quantitatively showed better retention after sleep. Later, researchers like William Dement in the 1950s observed that depriving people of REM sleep hindered certain learning tasks, hinting at REM’s role. By the 1980s, animal studies had begun to suggest that neural activity during sleep reflects prior learning (e.g., a 1989 study by Pavlides & Winson found that hippocampal neurons that were active in rats during learning had increased activity during subsequent sleep).

- Two-stage memory theory (1980s): György Buzsáki, David Marr, and others formulated the idea that the brain has a two-stage learning process: encode during wake, consolidate during sleep. Marr (1971) specifically theorized the hippocampus is a temporary memory store that trains the cortex, which was remarkably prescient. Buzsáki (1989) proposed that sharp-wave ripples in hippocampus during sleep are the mechanism for transferring memory to cortex – a bold idea later confirmed by experiment.

- Hippocampal replay in rats (1994): Bruce McNaughton and Matthew Wilson’s landmark study showed sequential replay of place cell activity in sleeping rats. This provided the first direct neural evidence of the brain practicing its experiences.

- Complementary Learning Systems (1995): McClelland, McNaughton & O’Reilly’s computational model demonstrated why a brain needs an offline period. Their simulations showed that interleaving learning (as if “training” on old and new data in batches) prevents catastrophic forgetting, whereas trying to learn new information straight into the main network (analogous to continuous wake learning) would overwrite old knowledge. Sleep naturally provides the interleaved training: the day’s new experiences are mixed with replays of older memories, which may explain why we sometimes see older memories or random past elements in dreams – the brain is maintaining them too.

- Ripple disruption impairs memory (2009): Gabrielle Girardeau and colleagues selectively interfered with hippocampal sharp-wave ripples in rats after learning. The treated rats failed to fully consolidate a spatial memory, proving a causal role for ripple-mediated replay. This was a critical piece of evidence linking the physiological event of replay to the behavioral outcome of memory.

- Systems consolidation in humans (2007–present): Jan Born’s group in Germany did studies where they cued memories during slow-wave sleep (by presenting an odor that was present during learning). They found that those memories were strengthened the next day compared to uncued memories, suggesting we can bias the system consolidation process. Conversely, disrupting slow-wave sleep or specific oscillations (like spindles) in humans can reduce overnight memory improvement. These studies underline that the slow-wave/spindle activity isn’t just correlated with memory consolidation – it’s driving it.

- Multi-region coordination and novel insight: Recent advances with electrophysiology in freely behaving animals and more sophisticated human experiments (targeted memory reactivation, closed-loop stimulation during certain sleep phases) have shown that sleep can do more than strengthen individual memories – it can reorganize information. The 2024 study in Nature Communications we discussed showed mice actually form new inferential memories only after a period of sleep. Similarly, human studies have found that creative problem-solving (like finding a hidden rule in a puzzle) often benefits specifically from REM sleep, whereas recalling facts benefits more from NREM. This aligns with the idea that NREM and REM offer different computational benefits – one more for stabilizing and integrating exact information, the other for abstracting and discovering new associations.

- Sleep in simpler organisms: Even fruit flies and bees, which have far simpler brains, need sleep for their tiny neural networks to function optimally. Fruit flies show learning impairments if they don’t get sleep after training (e.g. in courtship learning or memory of smells). When deprived of sleep, flies also exhibit “sleep rebound” – they’ll compensate by sleeping longer or deeper later. This suggests that even in invertebrates, neural plasticity requires an offline phase. In flies, researchers have observed changes in synapse structure with sleep vs. wake (synapses literally shrink during sleep, consistent with synaptic homeostasis theory). The conservation of these traits across evolution underscores that the algorithm of sleep-supported learning is fundamental to brains, not just a quirk of humans.

- Unihemispheric sleep (various animals): Species like dolphins, whales, and some birds can sleep one hemisphere at a time, as mentioned. This is often cited in support of the idea that sleep’s functions are local to the neural circuits. It appears that one half of the brain can undergo the slow-wave activity and memory consolidation processes while the other half stays alert enough for the animal to swim or watch for predators. After some time, they swap. The fact that they don’t just keep one hemisphere awake indefinitely implies that each part of the brain needs its offline period – again consistent with the “must update weights offline” notion. Interestingly, researchers have found that in unihemispherically sleeping animals, the side of the brain that was more active during the prior wake period tends to have deeper slow-wave sleep when it’s that side’s turn to sleep, suggesting sleep intensity can be use-dependent (the brain “knows” which circuits worked hard and gives them extra offline processing).

In summary, decades of studies across multiple levels (behavioral, electrophysiological, molecular) and species (from flies to rodents to humans) converge on the idea that sleep is the brain’s solution to the problem of continuous learning in a plastic neural network. Your description – daily inference mode and nightly training mode – is a spot-on high-level summary. The brain uses sleep to consolidate memories, integrate new information with old, recalibrate synaptic strengths, and even to perform general maintenance like clearing waste. All these processes are incompatible with normal conscious functioning, hence the need to periodically shut down sensory awareness and motor activity. In the eloquent words of Tononi & Cirelli, “sleep is the price the brain pays for plasticity” – it’s the necessary downtime for a highly adaptable (but delicate) learning system. Evolution has relentlessly optimized sleep (e.g. regulating its duration and intensity based on need), but it has never found a way around it because turning off consciousness is apparently the only reliable way to achieve the comprehensive upkeep our complex brains require.

Sources:

- Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. (2016). Synaptic homeostasis hypothesis: sleep as a cost of plasticityncbi.nlm.nih.govncbi.nlm.nih.govncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- McClelland, J.L., McNaughton, B.L., & O’Reilly, R.C. (1995). Why there are complementary learning systems in hippocampus and neocortexstanford.edustanford.edu. Psychological Review, 102(3).

- Wilson, M.A. & McNaughton, B.L. (1994). Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. (Discovery of replay in rats)picower.mit.edupicower.mit.edu.

- Girardeau, G. et al. (2009). Selective suppression of hippocampal ripples impairs spatial memory. Nature Neurosciencepubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Lansink, C.S. et al. (2009). Hippocampus leads ventral striatum in replay of place-reward sequences during sleepjournals.plos.org. PLOS Biology.

- Dave, A.S. & Margoliash, D. (2000). Song replay during sleep and vocal learning in zebra finchespubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Science, 290(5492).

- Rasch, B. & Born, J. (2013). About sleep’s role in memory consolidation. Physiological Reviews, 93: 681–766 (review)ncbi.nlm.nih.govresearchgate.net.

- Abdou, K. et al. (2024). Prefrontal coding of learned and inferred knowledge during REM and NREM sleep, 15:4566.

- Xie, L. et al. (2013). Sleep drives metabolite (β-amyloid) clearance from the adult brainpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Science, 342(6156).

- Hoel, E. (2021). The overfitted brain hypothesis: Dreams as regularizerssciencedirect.comsciencedirect.com. Patterns, 2(5), 100244.

***

S. Abbas Raza: I had Gemini 3 Pro read what ChatGPT has written above and check all the citations to make sure nothing was hallucinated or just made up, and Gemini did find one citation where ChatGPT got the name of a paper it cited slightly wrong (I have corrected it) but for the rest Gemini reported that, “I have reviewed the text from ChatGPT. The short answer is: This is an exceptionally accurate summary of the current neuroscience of sleep.” If you can find any errors, do report them in the comments please.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.