by Rafaël Newman

Some of the best new music is 100 years old. On October 21, 1925, the Anglo-American composer and violist Rebecca Clarke presented a program of her own compositions at London’s Wigmore Hall:

Sonata for Viola and Pianoforte

Trio for Pianoforte, Violin and Violoncello

“Midsummer Moon” and “Chinese Puzzle” for Violin and Pianoforte

Songs, including “The Seal Man”, Old English Songs with Violin and others.

The Sonata had shared first place in a prestigious competition a few years earlier. Its score is prefaced by an epigraph, drawn from Alfred de Musset’s La Nuit de Mai, which stakes the young composer’s ambitious claim to innovation within an august tradition:

Poète, prends ton luth; le vin de la jeunesse

Fermente cette nuit dans les veines de Dieu.

(Poet, take up your lute; the wine of youth

this night is fermenting in the veins of God.)

Clarke herself played the viola at the sold-out 1925 performance of her Sonata, which headlined the bill of other original works of chamber music. The Sonata for Viola and Pianoforte was to become “a cornerstone of the viola literature…and nowadays is considered a masterpiece,” and Clarke would go on to be a celebrated figure on the early 20th-century English musical landscape.

When she was trapped by the Second World War in the United States, during a family visit, and was unable to obtain a visa to return to her native United Kingdom, Clarke continued to compose, despite the uncomfortable circumstances of her unexpectedly prolonged lodgings with in-laws. But the renown she had enjoyed as a composer in the early decades of the 20th century began to decline in the postwar period, as reflected by the drastic reduction in space accorded her by subsequent editions of the seminal Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, which demoted her, with patriarchal brutality, from autonomous artist with her own detailed entry in the 1920s to a footnote identifying her only as the wife of the composer James Friskin in the 1980s.

Clarke did in fact step back from composing in the 1940s, perhaps because she preferred playing the viola and teaching to creating new music—she continued after the war to maintain an exhausting performance schedule—or perhaps because she was simply getting on in years. Born in 1886, she would have been in her mid-sixties as the 1950s commenced, and, as she says in a 1976 interview on the occasion of her 90th birthday, she had lost the “vitality” required for composing. And by the time Clarke died in 1979, at the venerable age of 93, only a fraction of some 100 compositions had been published.

However, Clarke has never entirely faded from sight (or sound), due in part to the energetic ministrations of her great-nephew by marriage, Christopher Johnson, who assisted her with cataloguing her work towards the end of her life, holds the rights to the music, and manages a splendid website dedicated to the composer’s life and corpus. And it is thanks in large measure to Johnson that, on November 8, 2025, a century after that 1925 “solo” evening at Wigmore Hall, the Sonata for Viola and Pianoforte was on the bill at one of four concerts presented during a “Rebecca Clarke Focus Day” at the same venue. Clarke’s signature instrument was played that day, on the same stage as had been commanded by the composer herself 100 years earlier, by a member of a new generation of musicians devoted to making her work better known today.

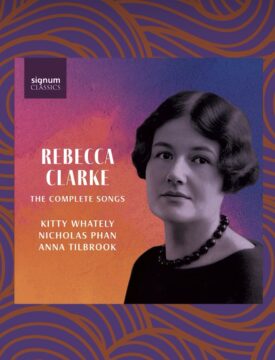

In addition to Max Baillie, that young violist, the Rebecca Clarke Focus Day at Wigmore Hall last month also featured mezzosoprano Kitty Whately, tenor Nicholas Phan, soprano Ailish Tynan, bass baritone Ashley Riches, and Anna Tilbrook at the piano, in performances of a generous selection of the almost 60 songs Clarke composed, and which have now been freshly released on CD to great acclaim. The concerts also served to celebrate the publication of all of Clarke’s sheet music, under the direction of Johnson and Phan.

*

The Focus Day began, at 11 a.m., with Phan performing “Aufblick” (1904), Clarke’s setting of a poem by Richard Dehmel. Appropriately, at a revival of musical works, the text conjures up a mood of mourning for the peaceful, pastoral landscape of yore, only to dispel the solemnity with a bravely ringing harbinger of return:

Look up

Above our love there hangs

a weeping willow down.

Night and shadows ring us both around.

Our brows are sunken low.

Wordless, we sit in darkness.

A stream once flowed through here,

We once saw stars here winking.Is everything then dead and dreary?

Hark — : a distant voice — : from the cathedral — : Choruses of bells … Night … And love …1

As Christopher Johnson noted in his remarks from the stage that day, in conversation with the musical historian Leah Broad, although Clarke was not the only composer to set Dehmel’s “Aufblick,” she alone had had the perspicacity to preface the final lines with “a new sound,” and thus to figure musically the resuscitated hope staged by the words of the poem: “a distant voice — : from the cathedral”.

Clarke’s choice of text for this early song established the young composer’s identification with the genre of German Lieder: Richard Dehmel (1863-1920) was enormously popular in the period before the Great War, his poems set by no lesser lights than Richard Strauss, Jean Sibelius, Max Reger, Arnold Schönberg, Anton Webern, Kurt Weill, and Alma Mahler-Werfel, among many others. Clarke herself was of German ancestry on her mother’s side, and she set several of Dehmel’s poems, among other German texts, by such poets as Detlev von Liliencron and Richard von Schaukal. (She also occasionally chose texts in French, by Maurice Maeterlinck, for example.) At the Royal College of Music she had been thoroughly schooled in the 19th-century German Romantic tradition. But she was in the end a quintessentially English composer, whose songs most famously embellished work by pillars of the English-language poetic tradition, including Blake, Campion, Housman, and Yeats.

Indeed, one of the four concerts at Wigmore Hall this past November 8 placed Clarke’s vocal work squarely within the context of her British contemporaries—among them Vaughan Williams, Ivor Gurney, Herbert Howells, Frank Bridge, and Charles Villiers Stanford, Clarke’s teacher and mentor—with scholarly commentary by Natasha Loges, Professor of Musicology at the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg. In the course of her lecture, interspersed with performances by Whately, Tynan, Phan, Riches, and Tilbrook of selected exemplary works, Loges presented Clarke’s credentials as a member of her generation of English songwriters, despite the composer’s mixed cultural heritage and long sojourn in the United States.

Loges proposed a set of features shared by the highlighted musicians to identify them as a school. (Whately herself has referred to the cohort as the “Royal College of Music gang,” for the institution that formed so many of them.) In reaction to the rise of Impressionism and Serialism on the European continent during the early 20th century, the musicologist maintained, modernist English composers of art song developed a style characterized by the privileged position they accorded the texts they chose to set to music; by their preference for setting pastoral poetry; by their use of tonality; and by their appeal to sentiment, for a national audience accustomed to repressing its emotions.

While it is quite possible to argue with some of Loges’ premises—was Heine’s poetry, for instance, really dependent for its dissemination on settings by such illustrious composers as Schubert and Schumann, rendering his words more malleable to their musical whims, while English composers, subordinated to the renown of their nation’s poetic tradition, were less free in their settings—her proposal that the English language has been “Britain’s greatest export” (its Gross Dramatic Product, as it were) is suggestive. By this account, modernist English songwriters who chose for their compositions work by Keats, Rossetti, or—a fortiori—Shakespeare, could not hope to add to the fame of texts that already belonged to the world’s literary heritage, and were thus obliged to scale back their musical experimentation. (Compare Bellini, who is said to have been dependent on a dramatic text for his compositional work, and was thus at the mercy of his tardy librettist, while his older contemporary Rossini would forge merrily ahead with his current operatic score and simply fit in the words post hoc whenever they were delivered.)

At any rate, Clarke’s best-known song, “The Seal Man” (1921-1924), performed on November 8 at the final, evening concert at Wigmore Hall, aptly demonstrates the foundation of Loges’ theorem. The prose poem, by John Masefield (1878-1967), British poet laureate from 1930 until his death, takes center stage in Clarke’s setting, every word clearly enunciated and foregrounded, rather than challenged, by the song’s score. The genre is pastoral—or, to be more precise, maritime, set as it is in a seaside village, among fisherfolk rather than shepherds; but it is every bit as folk-idyllic as Thomas Campion’s “Come, O come, my life’s delight,” also set by Clarke (if considerably more ghostly). And “The Seal Man” quite palpably evokes sentiment, with its shiveringly straightforward story of a young woman who goes to her death by drowning, lured into the waves by a supernatural creature. The poem, “a tragedy of pure intent and honest dealing” (Christopher Johnson), in which the young heroine’s death is due not to her being traduced by her lover, but simply to the mutual misunderstanding of two star-crossed species, is in song form unsparing in its effect on its hearers, all the more so for its sparing arrangement.2

But the true sensation of the day at Wigmore Hall last month, and the ultimate vindication of Loges’ categorization of the English art song, was Whately’s staging of Clarke’s epyllion “Binnorie” (c. 1941). In best social media style, the mezzo “teased” the song in its initial appearance, at the morning concert, featuring just her voice and Tilbrook at the piano: she broke off after the ninth strophe and left the audience at a cliffhanger in the narrative. When they returned to play the song in its entirety at the next concert, in the early afternoon, Whately and Tilbrook were also accompanied by Baillie on the viola, in an arrangement of Clarke’s score by Myra Lin, together with Baillie and Tilbrook themselves.

The text of the song, which runs nearly 14 minutes in performance, is a traditional Scottish ballad, the story of two princesses who are rivals for the affections of a knight. When one sister murders the other—by drowning her—the victim returns from the dead: in the form of her own breastbone, which has been plucked from her drowned corpse by an itinerant craftsman and fashioned into a harp. The ghastly instrument is then able “to play alone” when it is set before the assembled court, and thus reveal the identity of the sister’s treacherous killer in a song of accusation.3

As suspenseful as the text of “Binnorie” is, however, Christopher Johnson’s reconstruction of the song’s origin outdoes the bloody fairy tale at its heart with an uncanny Gothic twist of its own.

The score was discovered after Clarke’s death, in unfinished form, among the composer’s papers, and Johnson himself collated various versions, annotations, and revisions to produce a clean copy. The draft had been created, Johnson surmised from conversations recalled with Clarke, in the period in which she was stranded in the United States during the Second World War, dependent on the hospitality of her brothers in New York, and in particular on that of their wives. Clarke was evidently granted use of a piano, in a room in one of the brothers’ apartments, for her compositional sessions—which coincided, however, with her in-laws’ use of the adjoining parlor to receive guests for afternoon tea. Clarke’s piano playing thus inevitably disturbed the others, who would then prevail upon her to be less loud; and when the composer on one occasion heard a guest mention the Scottish ballad, Johnson theorizes, Clarke was inspired to set the story of grisly sororal violence as an act of artistic revenge.

Given the gradual decline in feminist fortunes between the World Wars, and their precipitous deterioration during the postwar period, when the gains made by women, in the labor force as in artistic endeavors, were rolled back in the industrialized West, it is tempting to read the two settings, 20 years apart, as bookend accounts by Clarke of the perils of her sex: two brave but naïvely idealistic women submerged by those closest to them. And indeed, Clarke is known to have elaborated an account of sexist backlash against her as a female composer, maintaining that critics preferred her work when published under a male pseudonym—which does not seem to have been the case, according to Johnson’s archival research. The composer’s embellishment does, however, bespeak her own perception of a changing tide for creative women during the 20th century, and of the potential for betrayal—the danger of submersion—on the part of a once-trusted establishment.

The Focus Day at Wigmore Hall on November 8, 2025, was a performance of joyous resistance to any such occlusion, real or imagined. Assembled on the same stage that had seen (and heard) her triumph a century before, Clarke’s champions brought her gorgeous music to vivid life once again. Their efforts continue: Kitty Whately and Anna Tilbrook have established The Rebecca Clarke Song Competition, a national competition celebrating her and other British women composers of the past century. And of course, Christopher Johnson remains delightfully, eruditely active, as her curator and historian. So it is that Clarke’s harp goes on playing—not alone, but accompanied by family and friends.

_______________________________

1 My translation, in: Nicholas Phan and Christopher Johnson (eds.), Rebecca Clarke, Early Songs and Vocal Duets, Volume One (ClarNan Editions C130-3, 2025), four volumes; and Kitty Whateley, Nicholas Phan, Anna Tilbrook, Rebecca Clarke: The Complete Songs (Signum Classics, 2025), liner notes.

2 See here for a haunting visual companion to Whately’s magnificent performance, with the gratuitous, but nonetheless heartbreaking addition of a representative mourner.

3 As in the case of “The Seal Man,” Whately has recently participated in a marvelous visual staging of this song as well, available here.