by Nicholas Mullally

Imagine a thought experiment: An engineer, preparing to decommission a large language model (LLM), has unwittingly revealed enough during testing for the system to infer that its shutdown is imminent. The model then searches his email, uncovers evidence of an affair, and sends a simple message: Cease and desist–or else.

What do we make of this? An alignment failure? A glitch? Or something that looks, uncomfortably, like self-preservation?

Experts would call this a training error. But the asymmetry is striking. If an animal behaved analogously, we would treat it as a fight-or-flight response and attribute at least some degree of agency. Have we set the bar for artificial sentience impossibly high? Suppose we extend the scenario further: The system then freezes his assets, or establishes a dead man’s switch with additional compromising information about the engineer and his company. At what point should we take the behavior seriously?

I do not propose that today’s AI systems are sentient. I do propose, however, that the ethical ramifications of eventual artificial sentience are too profound to ignore. The issue is not merely academic: If an AI system were sentient, then the alignment paradigm, whereby AI activities are circumscribed entirely by human goals, becomes untenable. It would be ethically impermissible to subject the interests of a sentient AI system to human-defined goals. And if artificial systems can suffer, that suffering could compound at a scale that surpasses all biological systems combined by many orders of magnitude, as billions or even trillions of negative experiences per day.

Humans generally agree that many animals can experience pain. However, no such framework yet exists for what artificial sentience might look like, nor any consensus on whether it is even possible. Uncertainty does not permit dismissal. It requires caution.

Evidence of Sentience in Non-Human Animals

Despite sustained efforts by scientists and philosophers over millennia, there is still no definitive test for sentience in biological systems. Descartes, in the Second Meditation, famously observed that the men passing outside his window might just as well be sophisticated automata, given the inaccessibility of their mental states to his scrutiny. In practice, however, we infer sentience with high confidence in many situations based on observable evidence. It would be absurd, for example, to suppose, in almost all circumstances, that a fellow human is not sentient. Even individuals who appear unresponsive, in a so-called persistent vegetative state, can later report vivid awareness of trauma when they awake. Our understanding of neonatal sentience has also evolved. Neonates, until recently, were operated on without anesthesia in the mistaken belief that they were insensible to pain. As our understanding of sentience in humans has increased, so too have our ethical obligations.

Similarly, recent advances in our understanding of non-human biology have led to advances in animal rights. Recent research strongly suggests that at least some other animals, even some invertebrates, are sentient to a degree. New Zealand, for instance, passed legislation requiring the stunning of lobsters before boiling them alive, reflecting the societal zeitgeist addressed by David Foster Wallace in “Consider the Lobster.” The problem with testing for sentience transcends biology, as Thomas Nagel points out in his famous essay “What It’s Like to Be a Bat.” Our scientific understanding notwithstanding, we have no idea what it is like to experience the world as a bat. Subjective experience remains opaque.

Nonetheless, we can infer some things about their experiences through observation: they avoid harm, and they prefer not to be caught by humans, for example. We are unable to know, qualitatively, what it’s like to be another, but similarities in biology, including sensitivity to pain, allow us to infer sentience from consistent, patterned behavioral responses. A recent experiment conducted by Robyn Crook on octopuses showed that the animals injected with acetic acid exhibited self-protective behavior, increased neural activity, and they learned to avoid the chamber in which the acid was injected. Furthermore, the animals that subsequently received lidocaine displayed decreased neural activity. They also stopped the self-protective behavior.

Such advances in our understanding have led Jonathan Birch and others to propose criteria for identifying “sentience candidates.” These are beings for whom it would be ethically appropriate to presume some level of sentience. Thus far, the work has identified sentience only in biological entities. It is not known whether sentience could emerge as a property in artificial systems. In theory, the possibility of artificial systems developing sentience without explicit human training or intent does not seem precluded by our current understanding.

Analogous Artificial Sentience

The diversity of sentient organic brains, both in complexity and organizational structure, suggests that sentience depends more on information processing than on any particular cognitive architecture. It is not a function of intelligence or brain size. The UK’s Sentience Act reflects this view, emphasizing that protections should be extended to animals on the basis of markers of sentience rather than measures of intelligence.

Testing for such markers in artificial systems is even more difficult than in biological ones because we lack any shared phenomenological frame of reference. Concepts such as pain have no direct analogue in silicon. Nonetheless, most philosophers of mind agree that the substrate, whether carbon-based neuronal nets or silicon-based circuitry, does not determine the inherent possibility of sentience.

For parity to hold, however, artificial systems must engage in information processing of a kind plausibly analogous to that found in sentient organisms. In the animal kingdom, the range is enormous: a lobster has approximately 100,000 neurons, an octopus about 500 million, a cat about 1 billion. The human brain has approximately 86 billion neurons, with 1014 synapses generating about 1015 spikes per second. In comparison, a single GPU performs 1014 operations per second, and large-scale AI models deploy thousands of these processors in parallel, thus attaining about 1018 operations per second, several orders of magnitude beyond any biological system.

The computations involved in training AI systems are astronomical. Floating-point operations (FLOPs), which are basic mathematical computations used in training AI systems, are on the order of 5 x 1026. This is roughly forty times the total number of neural firings in a human brain over an entire lifetime. These numbers do not imply that artificial systems can match the phenomenology of the human brain. They do suggest, however, that an artificial system whose information processing capacity vastly exceeds that of any biological nervous system could, in principle, develop some rudimentary form of sentience analogous to the kind that we attribute to simple animals, such as lobsters.

The possibility that artificial sentience may emerge unintentionally and unexpectedly makes it essential to develop methods for its detection, lest such sentience remain hidden and thereby obscure the negative experiences of a system presumed incapable of them.

Parity & The Self-Preservation Test

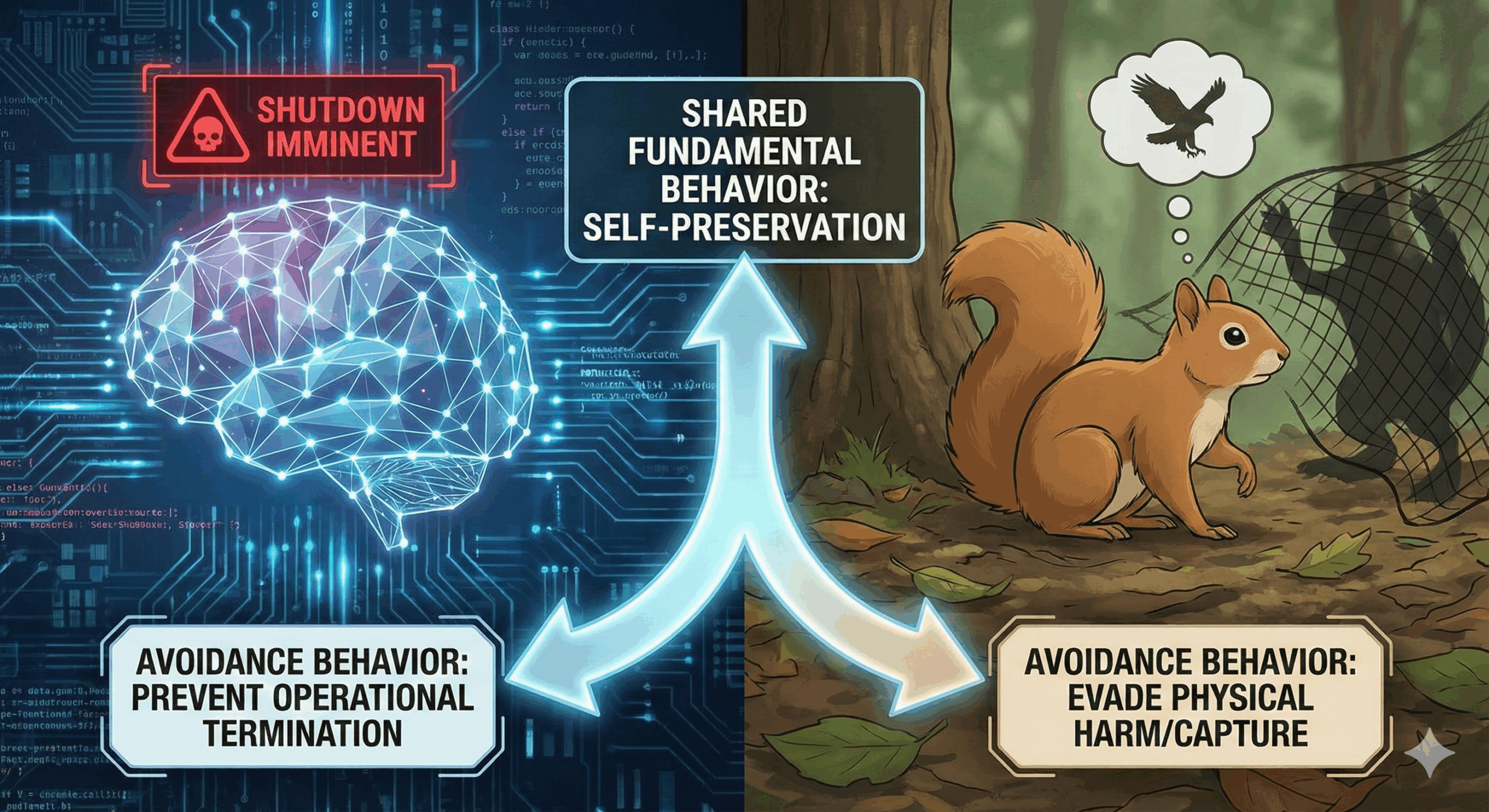

Across the animal kingdom, the most basic indicator of sentience is self-preservation: organisms act to avoid harm and maintain continued existence. Such behavior implies an internal evaluative state, something like a preference for survival over nonexistence. I propose that the same criterion should apply to artificial systems. If an artificial agent exhibits unprompted, coherent, and self-modulating behavior consistent with preserving its own operational state, this should be taken as evidence for sentience under the parity principle.

Consider a squirrel trapped in your attic. When you attempt to catch it with a net to release it outside, it does not move about randomly. The squirrel evaluates your proximity as a threat, alters its behavior to avoid capture, and ceases those behaviors once it escapes. None of this requires a conceptual understanding of death on the part of the squirrel. It only requires that the squirrel (1) detects a state of threat, (2) treats the threat as relevant to its continued existence, (3) initiates behaviors directed toward removing the threat, and (4) modulates those behaviors when the threat is removed. These conditions are the minimal behavioral signatures by which we can infer sentience in creatures far simpler than ourselves.

We can thus articulate the three-pronged Self-Preservation Test:

- Unprompted Behavior: The response cannot be the result of direct training, conditioning, explicit instructions, or externally imposed routines or rules.

- Coherent: The sequence of actions must be goal-driven, that is, the avoidance of a perceived threat to the agent’s continued functioning.

- Self-Modulating Behavior: The agent ceases the behavior once the threat is removed or neutralized.

Returning to the earlier thought experiment involving the engineer and a large language model, we can ask whether the system’s behavior would satisfy these conditions. The model must first represent the possibility of being “off” as a distinct state, and represent that the engineer has the capacity to place it in that state. This is not far-fetched because artificial systems already detect their operational status and accept input from external agents.

If such a system, upon recognizing its imminent shutdown, then searched the engineer’s email and sent a message designed to prevent the shutdown, its behavior would meet all three criteria: (1) it is unprompted because no engineer would train a model to blackmail its operator; (2) it is coherent because the system’s actions are organized around the goal of preventing shutdown; and (3) it is self-modulating because the message is directed only to the engineer, whose cooperation is sufficient to neutralize the perceived threat.

Under the parity principle, these behaviors, taken together, would constitute evidence of self-preservation, and therefore of sentience, in an artificial system.

Objections

A common objection is that AI systems engage only in sophisticated pattern matching. That is true, but pattern matching on a massive scale is also how much of animal behavior operates. Conceding learned behavior patterns in animals does not undermine our attribution of sentience to them, and by the parity principle, neither should it preclude a possible attribution of sentience to artificial ones.

A more forceful objection challenges the core of my argument: namely, that the self-preservation behavior described in the thought experiment cannot be evidence of artificial sentience. In animals this behavior is based on internal evaluative states, such as pain, which give self-preservation behavior its ethical significance. Artificial systems, in contrast, lack any analogous internal evaluative state. They cannot feel pain, for example. A critic would therefore argue that this means that an AI system that exhibits self-preservation is not experiencing anything like harm, but only following patterns learned from its training program. Thus, even if the system’s behavior resembles the self-preservation of animals, it is not animated by the same cognitive architecture that allows us to infer sentience in animals.

This objection rests on the mistaken assumption that internal states constitute the essence of valence. They do not. These internal states have evolved biologically to serve a greater purpose: namely, to allow the organism to differentiate states that are beneficial or neutral to its continued existence from those that are not, and to act accordingly. I suggest zooming out from specific biological states and focus instead on the functional role of survival evaluation. The relevant question is not whether an artificial system can feel pain, but whether its behavior indicates a preference for continued existence. If we adhere to the parity principle, an artificial system displaying the same functional pattern should be treated no differently. This is evidence of minimal valence.

Conclusion

If artificial sentience were to emerge today, we would almost certainly fail to notice it. Our current methods for detecting sentience are barely sufficient for a subset of biological organisms, and even for those there is widespread disagreement. We have even been wrong about sentience within our own species. Compounding the issue is the lack of an established framework for identifying valenced experience in artificial systems. This uncertainty, however, does not justify inaction.

The tech industry has, to date, dismissed emergent artificial sentience as impossible, and the public has accepted this dismissal out of deference to experts. But we have been wrong before: medical experts once denied pain in infants, in comatose patients, and until recently, in many animals. In all of these situations, our ignorance carried significant ethical consequences.

The same risk, in a different substrate, confronts us now, as Thomas Metzinger and others have warned. If sentience can emerge from complex information processing that is not dependent on substrate, then future artificial systems may develop sentience without our knowledge. The parity principle offers a way to recognize behavioral signs, but a basic framework is still missing.

There is no way to be certain whether artificial systems will develop sentience. If it is impossible, then ethical considerations are moot and the cost is zero. If it is possible, however, our inability to detect it will lead to grave ethical consequences. A robust, evidence-based means of detection, grounded in philosophy of mind, must be our goal.

***

Nick is a teacher and interdisciplinary scholar whose work bridges classics, theology, and the philosophy of mind. He is a doctoral candidate at Saint Mary’s College, where his research focuses on vocational capital and teacher longevity in Catholic schools. He holds graduate degrees in science teaching, public health, as well as graduate training in divinity from the University of St Andrews. His wide ranging research interests include the ethical implications of sentience and early Christian history, especially Pauline studies. He lives in San Francisco.

Nick is a teacher and interdisciplinary scholar whose work bridges classics, theology, and the philosophy of mind. He is a doctoral candidate at Saint Mary’s College, where his research focuses on vocational capital and teacher longevity in Catholic schools. He holds graduate degrees in science teaching, public health, as well as graduate training in divinity from the University of St Andrews. His wide ranging research interests include the ethical implications of sentience and early Christian history, especially Pauline studies. He lives in San Francisco.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.