by Michael Liss

No Congress of the United States ever assembled, on surveying the state of the Union, has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time. In the domestic field there is tranquility and contentment, harmonious relations between management and wage earner, freedom from industrial strife, and the highest record of years of prosperity. —Calvin Coolidge’s “Annual Address,” December 4, 1928

“Silent” Calvin Coolidge was a man of few words, but he might have uttered those particular few with a sense of satisfaction. Times were good in America in 1928—not for everyone, not for every industry, but, in the main, there were more jobs that paid a living wage, new industries that had great promise, and less rancor both politically and between the classes.

The Roaring Twenties had begun with a political earthquake—an electoral realignment. America wanted something different from the status quo, and the status quo was Woodrow Wilson. Wilson’s second term was dominated by America’s late entry into the war, debates over the League of Nations (as the country was growing more isolationist), and general domestic unrest. He was a man of great intellect and serious talent, but, if there was a sunny, optimistic side to Wilson, he hid it well. This was even more so after the serious stroke he suffered in October of 1919, a time in which he essentially sequestered himself from the public and even from most of his Cabinet. It is perhaps a measure of his monumental ego that, post-stroke, he still saw himself as a potent political force, not merely able to discipline his own party, but to convince the public to give him a third term.

Any rational viewer would have seen that as completely impossible, and a third Wilson campaign never got off the ground, but it was not merely his dyspeptic temperament, but also his policies which more and more of the country doubted or outright rejected. The forces that had given him the White House in the first place now inverted themselves. In 1912, Teddy Roosevelt had sought to reclaim the Presidency from his former VP pick, now turned President, William Howard Taft. TR wanted a continuation of his Progressive policies, and Taft was by nature and ideological preference a conservative. Losing the White House to a Democrat (and a Southern one at that) convinced many in the GOP to move further away from the Progressive wing and Progressive values. That shift was echoed by a smaller (but decisive) transition in the views of the electorate.

It was time. Republicans were going to win in 1920 if they picked anyone remotely normal, and Warren Harding, who campaigned on a “return to Normalcy” caught the mood perfectly. He wasn’t the first choice for many, and few thought of him as a powerhouse, but that made for a perfect compromise candidate, and he took the nomination on the 10th ballot. Then he mixed up his “front porch” campaign with his slogan, a dollop of common-man geniality and a breezy “better times are on the way,” and it was magic. The Harding-Coolidge ticket crushed the Democratic nominees of James Cox and pre-polio Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Republicans also gained a stranglehold on their majorities in both the House (+63 seats) and the Senate (+10). 1921 was to be a very Republican government.

The core Republican philosophy crassly (and somewhat unfairly), best described as “the rich know better than we do,” led to lower taxes, the end of regulations, including health and safety ones, and a general withdrawal of the government from both the wealthy and common man and woman’s economic lives.

They probably couldn’t have picked a better time for it. Yes, there was corruption (hat tip to Mr. Harding and any number of lesser or brighter lights) and yes there was favoritism, and yes, the big guys got a great deal while the common man just comparative crumbs. All that being said, those crumbs, combined with technological advances, made a palpable change in the lives of many. Inequality in distribution of benefits did not mean widespread insufficiency, and the public enjoyed their share. You could not only find a job building a car, but you could also make enough doing that to afford one of your own. Life was pretty good, and Harding, for all his low-brow cronyism, did make two very good choices with respect to the economy: the internationally renowned Herbert Hoover for Commerce Secretary, and the widely respected Thomas Mellon for Treasury Secretary. Both were devout believers in the supremacy of the wealthy (which led to some rather “cold” decisions), but both were focused on the advance of the economy as a whole, rather than mere extraction solely for the good of the few. Hoover vastly extended the reach of Commerce and transformed it into an advocacy center for American business. Mellon was an unflinching evangelist for what used to be thought of as economic conservativism—bring down the national debt, reduce taxes on the wealthy (who would, in turn, invest it in growth-oriented business), open markets, support a strong currency, and ease regulations. Mellon was so trusted by so many that Congress gave him a unique power—the ability to directly return tax receipts to wealthy individuals.

It all worked, imperfectly and unequally, but it did work. After Harding died in office, Calvin Coolidge succeeded him in 1923, easily won renomination, and trounced the eventual Democratic ticket of John Davis-Charles W. Bryan. Peace and prosperity, even if uneven, is a potent political tool, and Coolidge had accomplished both. Mellon’s economic ideas held sway and, where needed, obtained Congressional approval. Coolidge almost certainly would have cruised to a second full term, but ruled it out. The field was open, but Hoover was certainly on the short list. His most likely opponent, Frank Lowden of Illinois, dropped out after the GOP inserted a Platform plank repudiating support for a farm relief bill. Hoover was ultimately nominated on the first ballot, then overwhelmed New York’s Al Smith (the first Catholic candidate) in the 1928 general election. As irony would have it, Hoover’s acceptance speech, delivered several weeks later, would include the following: “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of this land.”

And why not? In less than a decade, a new type of economy, more technology based, had grown up alongside the traditional one. You didn’t need to live as your grandfather did. In reach were radios, cars, phones, washing machines, refrigerators—and, to use those, you needed more infrastructure, including widespread electrification.

New opportunities were also available in the world of finance. The person who was looking at a Ford could also afford to dabble a bit in stocks and bonds, visiting his broker, perhaps taking out a margin loan to enhance his return. If he wasn’t comfortable selecting individual stocks, he could pick an investment trust, run by the professionals who knew all the inside skivvy and had access to even more leverage. Why invest the $750 in the Ford when you could buy Ford stock, margin it, say, five times (because you are cautious—the broker would allow more) and when it goes up—well, you can now have the car and the stock. It’s going to work, all of it, and before you know it, we will be on easy street.

Foolish greed? Maybe, but it was normalized and encouraged. Brokers found themselves lending great amounts of money at rates up to 12% just to hold onto the borrower’s stock as collateral. Since the market was continuing to rise, where was the risk? The Federal Reserve believed that borrowed money should be invested in businesses, in plants and equipment, but there was nothing that stopped banks from borrowing from the Fed at whatever re-discount rate existed at the time and lending it into the market—at twice or more the rate, and again, presumably no risk. Foreign money poured in, partially because of currency and gold standard issues, partially because it was just so profitable. Who turns down an effortless return? Immigrants were right, the streets of America really were paved with gold.

On March 4, 1929, Herbert Hoover was sworn into office. His Inaugural Address was optimistic, as he was optimistic.

Ours is a land rich in resources; stimulating in its glorious beauty; filled with millions of happy homes; blessed with comfort and opportunity. In no nation are the institutions of progress more advanced. In no nation are the fruits of accomplishment more secure.

Hoover now led that shining city on a hill, and in March of 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was at 308. That number desperately needs context. This last Friday, October 31, 2025, the Dow closed at 47,562.87. For just one stock, Ford, the one-day volume was almost 69 million shares. The scale and scope of what is done today would be thought of as impossible in Hoover’s time.

308 actually happened to be a very favorable number, and not just because it was Hoover’s starting line. In August of 1921, a few months into Harding’s Administration, it had been 63, so it nearly quintupled. Hoover’s luck seemed to hold. By September 1929, the Dow hit 381—another 24% gain in just a few months.

And then, some strange sounds began to emanate from wherever caution lived. Little cracks had begun to appear in the “real” economy. Maybe there was a little bit of a stock market bubble, and maybe that bubble was showing a bit of strain. On October 23, 1929, there was a late-in-the-day selloff, taking about 4.6% of the total market capitalization with it.

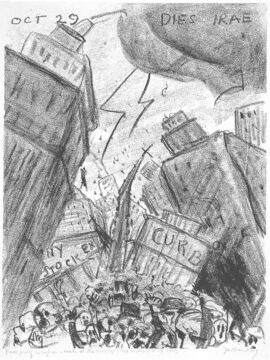

Thursday, October 24, countless hearts beat with fear. 12,894,650 shares passed hands (an unthinkable number at the time), and, in the words of John Kenneth Galbraith, “many of them at prices which shattered the dreams and the hopes of those who had owned them.”

Everything was going wrong all at once. The volume was too much for the ticker to handle, so current prices (whatever they might actually have been) were unavailable. That fed into margin-loan issues: how do you know your collateral is worth enough to support the loan, and if it isn’t, how much has to be sold (and what amount needs to be realized)? A cascade occurred … declining prices led to selling; the lower prices dropped the value of collateral, which led to more selling; those that had been leveraged lacked the cash to maintain their loans, which led to liquidations. In the middle of this were stop-loss orders, put in by brokers who had made those margin loans, and who wanted to protect their collateral. Each stop-loss triggered meant more selling and even lower prices. The audience in the visitor’s gallery was transfixed with horror, often, when new prices were displayed, audibly gasping. By 12:30, the officials of the New York Stock Exchange thought it too much and closed it to the public. One of the last visitors was a Mr. Winston Churchill. It was a moment filled with unintended irony: in 1925, when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, he had been central to returning Britain to the Gold Standard, an overvalued pound and a strain on and distortion in the international trading and finance system.

But there was hope (for the moment) by the intercession of the big men in the business who decided to perform an intervention, or, in the language of the time, provide “Organized Support.” They met in the offices of J.P. Morgan and Company, these powerful men, and decided to pool their resources to provide support to the market. Thomas Lamont, senior partner at Morgan’s, walked out, suave and debonaire, met with the press, and described the situation as “a little distress selling on the Stock Exchange.” His words and his insouciance calmed the markets. At 1:30, Richard Whitney, acting President of the New York Stock Exchange, appeared with cash in hand, and began to put in orders to buy. The market firmed.

But for whom and for how long? Who was still in, how much did they have left, and were they sold out by their brokers when their hypothetical margin balance was calculated? Established figures sought to replace full information with soothing words. Multiple variants of “fundamentally sound” were employed, and, in fact, some said the event was a beneficial one—one wanted to see those nasty speculators purged. The markets steadied in its Friday and Saturday sessions. It was over, a bit of a harsh knuckle-rapping, but for the best.

Weekends are for running in the park, enjoying your friends and family, reading a good book, doing some chores. If the investing public had just stuck to that …. Monday might have been just another day. But they didn’t. Instead, people took stock of where they were, what they still possessed, and just how frightened they were.

Quite frightened, it turned out. Volume was somewhat down from Thursday, but still empirically huge. Top quality stocks were under enormous pressure. The market as a whole lost almost 13% in the black hole known as Black Monday. There were brief rumors of more organized support, and, at 4:30, another meeting of the bankers, but they also had time for evaluation. An “orderly” market is what they sought now. Orderly meaning no “air-holes,” but not a commitment to maintain prices.

Monday was terrible. Tuesday, Black Tuesday, was horrific. Volume soared from already high levels to 16,410,030, an impossible-to-conceive of number. Again the ticker ran behind by hours, and air-holes were popping everywhere … with no organized support in sight. There’s a story about White Sewing Machine Company, which had traded as high as $48 earlier in the year. Monday night, it closed at 11, and, on Tuesday, someone (supposedly a sharp messenger) put in a bid at $1 for a block—and got it, given the absence of buyers. At the very end of the day, there was a short rally, when some of the better-quality stocks firmed up, easing the losses to about 12%, but the damage was done. As for the bankers, they met again, twice, but, as nothing was forthcoming, the public mood turned toward suspicion. Were these fine gentlemen selling stocks?

At least one was. Albert Wiggin, head of Chase National Bank, was shorting stocks—or more accurately, “stock”—in Chase National Bank! He made a fortune—over $4M and managed to shield the profit from taxes to boot. As a result of this “investment activity,” there is a Wiggin Rule forbidding similar actions by Directors of corporations.

On Wednesday October 30, following the two worst days in market history, the market rallied, confounding all expectations. No one could be sure why … a bit of support, a declaration of a special dividend, an encouraging comment from John D. Rockefeller, who had been publicly silent for decades. The upward drift gave the Exchange the opening to shorten the hours on Thursday, and close for Friday and Saturday. With the air saturated with comforting words and symbolic gestures, and the sense that the worst may have been in the past, the focus over the weekend was on catching up, getting through the paperwork. A few technical adjustments were being made—margin requirements were eased, the Fed lowered the re-discount rate, and Federal Reserve Banks commenced open-market purchases of bonds. The system had taken a body blow, but it was starting to find itself again. Monday would be fine, a continuation of the previous Wednesday and Thursday rally.

It wasn’t. Monday was bad. We can tick off several factors, including the growing realization that the investment trusts that so drew in investors were, in a weak market, a recipe for leveraged-based disasters. Tuesday was Election Day, so the markets were closed. Wednesday was shot-through with weakness, particularly with the perceived blue-chips. Now bad “real economy” data was coming in—particularly in the important commodities area. For a couple of days more, the market moved listlessly, just trying to get its bearings, and then went through yet one more sickening dive, November 11 through 13. By mid-November, the Dow had lost nearly half its value, and other indices indicated broad weakness. The carnage in the investment trust area, which wasn’t part of the Dow, was gigantic.

President Hoover was spurred to action. He brought industry leaders in for talks. On November 19th, he gave a short statement to the newspapers indicating he wouldn’t be talking about those talks. Following that statement, he engaged in more talks. Hoover seemed to think he could broker a solution to the crisis—if there was a crisis.

An anxious public sensed there was more to come. Wild stories floated around, some true or half true, but most possessing at least at least as much credibility as some reassuring profundity floated by some reassuring pundit. What people did know was that life might never be the same, and, for some, it was over. Two investors who maintained a joint account had gone bust. They took a room on a high floor at the Ritz, and, holding hands, jumped.

Others would follow, if not literally, figuratively. Remember the number 41.22, because a long night was about to begin. We will pick that up next month.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.