by Michael Liss

… I watched with increasing apprehension the Third Republic go downhill, its strength gradually sapped by dissension and division, by an incomprehensible blindness in foreign, domestic, and military policy, by the ineptness of its leaders, the corruption of its press, and by a feeling of growing confusion, hopelessness, and cynicism (Je m’en foutisme) in its people. —William L. Shirer, The Collapse Of The Third Republic

“Do you think America’s political system can still address the nation’s problems or is it too politically divided to solve its problems?” 33% said “can still address”; 64% “too politically divided.” —Results of a nationwide New York Times/Siena poll of 1,313 registered voters conducted from Sept. 22 to 27, 2025.

Let me take you back 10 years, to the fall of 2015. An email from a good friend, the type of person America doesn’t manufacture anymore—both a scholar and an international businessman, multilingual, connected to an array of influential institutions and people, and a moderate Republican.

He was writing just after the November 2015 Islamic State-sponsored Paris and Saint-Denis terror attacks, which left over 100 dead and 400 injured. The breakdown in civic culture was part of his concern, but it wasn’t the only one. He was profoundly worried about the startling rise of Donald Trump. He wondered if we in the United States weren’t also turning toward the anger, the xenophobia, and the dysfunction that characterized the discourse in 1920s and 1930s Europe. That was the atmosphere that brought then to a Hitler and a Mussolini, the “confusion, hopelessness and cynicism” in France that Shirer wrote of. Could it happen here?

For context, Trump had entered the contest for the GOP Presidential nomination on June 16, 2015. In his announcement speech, he mentioned economic themes like deficits and offshoring of jobs, but also pounded (with explicit, highly charged language) on illegal immigration and the threat of Islamic terrorism. Deficits and immigration were standard topics for any Republican, but Trump wasn’t “any Republican”—he was on his own island, launching what seemed a vanity candidacy by a man with a potty-mouth who sprayed people and entire ethnic groups with insults. His opponents scorned him, advertisers distanced themselves from him, and odds-makers were positive he had almost a negative chance of winning. Public polling seemed to bear them out. A June 2015 NBC/WSJ Poll had Jeb Bush in the lead at 22%, Scott Walker at 16%, Marco Rubio 14%, Ben Carson 11%, then six others (Mike Huckabee, Rand Paul, Rick Perry, Ted Cruz, Chris Christie) …. and, in 10th, the last position to qualify for the first GOP debate, Carly Fiorina. Not a Trump amongst them. There was something Trump did excel at—he was soundly rejected by the Republican public—16th out of 16 to the question of “Could you see yourselves supporting this candidate or not?” at a formidable minus 34%. It wasn’t that the Republican voter didn’t know Trump. They did know, and what they knew they didn’t like.

But Trump had found something most of the major Republican candidates, conservative commentariat, and the media, had missed. His inflammatory language, which they saw as crude, un-Presidential (and they hoped) disqualifying was heard as a beat to quarters by others. Trump might be a blowhard, but at least he didn’t sound like a lawyer or a professional politician. All those guys did was talk, and for all the rounded, consultant-tested phrases they laid out like tapas on a tasting menu, it was Trump, with his ill-mannered vitality, that got through.

The narrative began to move, and the polls followed. By early September, the 150-1 shot was the frontrunner. A CNN/ORC poll had Trump at 32%, Carson at 19%, Jeb 9%, Cruz 7%. Huckabee and Walker at 5%, and everyone else, including Rubio, below 3%. What’s more, 51% of Republican respondents called illegal immigration the most important issue facing the country, and, having made the issue his own, Trump dominated among that group.

Trump could win. It was crazy: Republicans had some hard-boiled talkers amongst them—shock-jocks like Rush, serious men like Pat Buchanan, but this was the team that usually nominated accomplished, mainstream adults. That fling with Goldwater in 1964 was … a summer thing, and then back to dating the Rotarian set.

Still, I thought my friend was overstating the risks. The American political system has almost always shown a type of awkward agility in dealing with fringe movements. It incorporates them, shaves the edges off them, feeds them a few crumbs (or sometimes a part of a loaf), and moves on. The same has been true with fringe candidates. They may develop a following—George Wallace, Henry Wallace—but ultimately voters tend to come home. So do the ultimate nominees, as they adjust their message to a broader audience. Only in times of real duress (since Lincoln, that would be Reagan from Carter, and FDR from Hoover) do fundamental policy and tonal changes come.

That was my framework in 2015 and early 2016, and I watched with a bit of awe at Trump’s sheer skill in picking off one Republican candidate after another. He’d target an opponent, trash him (or her) while the others stood by silently, and move on to the next. Why did the others stay quiet? I suspect at least part of it was opportunism. They were so sure Trump would be rejected (if only the field were smaller) that they thought Trump was the 340-pound offensive lineman and they were the speedy running backs. Trump would plough the field; they’d spike the football in the endzone. What they didn’t get, and I didn’t see, was that Trump was well past that point—he was already in the locker room. Despite the literally hundreds of negative editorials and biting columns (many of them written by current Trump acolytes), the nomination was his, and, as would be seen, the Presidency was coming.

My friend was right. Something had happened to not just the GOP, but also, more broadly, to the American electorate. A previously unrecognized passion created a new voting block of disaffected voters. Trump had tapped into it. Hot issues had brought hot language and (potentially) hot policy responses—and those hot policy responses were just fine with people who had accepted tepid “frameworks” before.

But was the implied threat of an American variant of 1920s’ and ‘30s’ European dystopia a likely one, or would we just muddle through, as we always had? After all, Trump was a “businessman” who made “deals,” and, to many people, that meant “realist.”

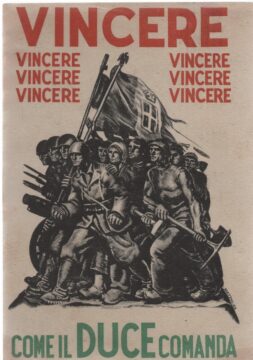

Again, let’s go back in time for context. The 1920s and 1930s had uncovered cracks in the foundation of democracies and enhanced the appeal of one-party or even one-person rule. The Weimar-Era German experiment in democracy had failed miserably, collapsing under the combined weight of several economic and social factors it showed itself unable to address. Look closely, and you can see how many might have felt the 1933 Hitler was inevitable. In Italy, Benito Mussolini went from obscurity to being appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III in just a few years. We tend to think of Il Duce as a clown now, but that would miss his stunningly effective roll-up of existing institutions through legal means mixed with muscle. By the late 1920s, Italy was a one-party state with a supreme ruler—with the cooperation of the other institutions of importance, including business and the Church.

Fascism and Nazism offered not just order and jobs, but also modernity, a restoration of national pride, a participatory tribalism. Such are the things that can excuse in some minds and in some consciences some of humanity’s worst atrocities.

What of France? Along with some of the same economic pressures felt elsewhere, it experienced class conflict, the appeal (and threat) of socialism, petty jealousies and big ambitions, a military class mired in the tactics and disciplines of World War I, and on it went. The Third Republic mirrored some of the worst qualities of its political and military leadership—too much pride, too little focus on meaningful action and results, and seemingly no vision whatsoever beyond its borders.

So, when in September 1938 Hitler demanded a piece of Czechoslovakia called the Sudetenland, France (and, notoriously, England) went to Munich and gave it to him. What followed is much less remembered, but the smaller sharks then circled around abandoned and betrayed Czechoslovakia and gobbled the rest of her up, with Hitler returning for one last bite.

Munich proved out a central organizing idea of Hitler’s military and diplomatic strategy—the West was weak and unwilling to commit. They showed it again when Germany signed a pact with Russia to divide up Poland, and, after a September 1 German invasion, they hesitated before honoring their treaty obligations. Hitler knew with whom he was dealing—and that he could pause without consequences after ingesting “his” share of Poland. An eight-month “Phony War” began without any meaningful repercussions being visited on Germany.

In April 1940, Germans took a medium-sized bite by attacking Denmark and Norway, and followed it, on May 10, with a massive assault on Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and parts of France. In many places, they met minimal resistance, but, where they found it, the Wehrmacht armies, supported by the Luftwaffe, swept it aside. Planning and execution were remarkable. “Fortress Holland” fell in a week. By May 13, German forces crossed the Meuse River. On May 14, the Germans had breached the Meuse-Albert Canal line in force and entered France just west of Sedan. The next day saw General Guderian’s XIX Panzer Corps break through the French line and head west into open country, moving so rapidly that it seemed he was putting his forces at incredible risk—yet he continued to advance, freezing huge Belgian, French, and British Expeditionary Force armies. The Dunkirk “miracle” rescued some of these men, but would also cause friction between the French and English leadership. A lot more British soldiers than French were evacuated, feeding French suspicions that England was not a reliable ally, and perhaps making a deal with Hitler would be the better way out.

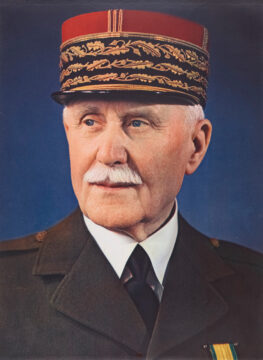

The dizzying speed and technical brilliance of the Germans was enhanced by the utter unpreparedness of the French. Their military crisis became a political one (the French Army was extraordinarily adept at avoiding blame), and, on May 18, they brought into the government Marshal Philippe Pétain, the 84-year-old “Lion Of Verdun” to give confidence and show solidarity. Whatever message it sent did nothing to slow down the Germans, who followed success with more success.

On June 14, 1940, Paris, having been declared an Open City, fell to the Germans. June 16, with the coming Fall of France obvious, and both the military and government desire for an armistice insatiable, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned, recommending to President Albert Lebrun that he appoint Pétain in his place.

What could the old man do? The Germans already occupied roughly 60% of the country. There would be no escaping their vise of steel, no way Hitler couldn’t take whatever he wanted. The French military and civilian leadership had put themselves in a box. The Generals wanted to stop the fighting, but didn’t want the dishonor of asking for it—and some of them convinced themselves the army was essential to maintain domestic “order.” The politicians wanted to maintain their power—but what power could they possibly have in a country dominated by the Germans? The astounding collective responsibility for an incomprehensible collapse was accepted by no one, except by the one person whose reputation was intact—Marshal Pétain.

He went on national radio and announced, “I make France the gift of my person,” and asked the Germans for an armistice. The Germans gave one—an armistice without honor in the very railcar where Germany had to accept its own defeat in 1918—but an armistice, nonetheless. For the French, General Charles Huntziger headed the signing team. Huntziger insisted that he not merely be authorized to sign, but ordered to by the French government.

If the story had ended there, a great deal of moral damage (and post-war self-examination and recrimination) might have been avoided. The Germans would have occupied all of France, taken what they wanted from it, and made it a vassal state like other European countries that had been brought under the yoke. It would have stayed that way until D-Day led to liberation, but perhaps French honor and integrity—and that of Marshal Philippe Pétain—would have remained intact.

Instead, the Third Republic had a second collective failure, and the Marshal made an unforgivable choice. Under the influence of Pierre Laval, twice a former Prime Minister carrying a grudge for having been kept out of high office since 1936, the National Assembly almost unanimously voted itself (and the Third Republic) out of business, but not before vesting in Pétain the unlimited authority to draft a new Constitution in such manner as he desired. Of course, Pétain was not exactly a draftsman, nor did he have relevant legislative experience, but there was a man who did—the very same Pierre Laval, who would be Deputy Prime Minister to Pétain’s Prime Minister, and later Prime Minister to Pétain’s Chief of State in the new form of government. Suffice to say that the relevant adjective in describing the grant of authority was “vast.”

A collaborationist regime was set up in Laval’s hometown of Clermont-Ferrand, and later in Vichy, with Pétain nominally in charge, and Laval acting as the true head of the government. The Marshal’s role was to act as twinkly eyed guide to conservative values. Laval had long been thought of as a Fascist with a desire to govern without restraint. These two streams met in Vichy in a complementary way.

Maréchal Pétain was an island of calm, an old and old-fashioned man possessing old-fashioned ideas that many saw as virtues and most as honestly held. In the Marshal’s view, it was his duty to spare the French people from physical destruction, to resist left-wing ideology, and to restore traditional values of Work, Family, Fatherland. A “National Revolution.” A bit of a cult grew around him—Vichy set up an entire division dedicated to producing what we would now call Maréchal Pétain Merch.

Such was the value of Pétain’s gift of his person. He gave his countrymen the remnants of a national pride, an expiation for their sins. And much of France accepted. They went back to their lives, went back to their work, and closed their shutters to the sight of what else was going on, and upon whom it was being inflicted.

Much of the “what else” came from Pierre Laval, and much of that was truly odious. Under Laval (who served more than one term, although not consecutively, having irritated Pétain), the country sorted itself out into winners and losers, neighbors informing on one another, property confiscated, shops closing, the French security services coordinating with the Gestapo, political enemies being rounded up and imprisoned, Jews being serially discriminated against and then deported to concentration camps, and even Frenchmen volunteering to serve in the Charlemagne Division of the Waffen SS. There were an astonishing number of deaths for which responsibility could be laid directly at the feet of Laval—more than 150,000 for a country nominally at peace —and Laval wouldn’t regret a single one of them.

It’s this last part that I think my friend would have pointed toward. Our democracy has survived politicians from across the spectrum, blacklists, boycotts, terror bombings, even a Civil War. It would, in my opinion, rise once more and unite to defeat a Hitler. It would, I think and hope, find a way to put aside the differences that 64% of Americans say our current political system cannot address and find a way. But can it survive the thirsts of ambitious men and women who, like Pierre Laval, just don’t care about the price others may pay to fulfill those ambitions? Can it endure the turning away from the sight of injustice done to others, or, worse, fail to resist the urge to pile on when you don’t like those others? That will take courage, and soul.

My late friend and his generation (he would be 95 now), observing both the worst and best that humanity had to offer, had those qualities. Do we?

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.