by Sherman J. Clark

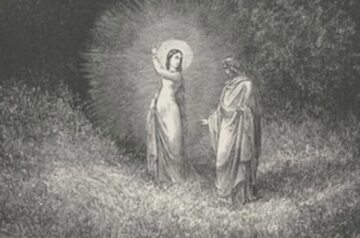

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

We too are often in a kind of dark wood—a thicket of distractions, manipulations, and half-truths. And we are surrounded by guides of a sort—marketers, algorithms, prosperity preachers, podcasters and influencers of every sort, all competing for our attention and trying to shape our desires. But unlike Beatrice, they do not aim to elevate or orient us toward what nourishes. Their purpose is to capture and monetize our attention, to keep us scrolling and buying and craving.

This is not just an annoyance. It is a crisis of desire. Our wants—so deeply bound up with our hopes, our fears, our sense of meaning—are increasingly manufactured to serve others’ ends. If desire is the engine of our striving, we are in danger of running on fuel that corrodes us.

This is particularly evident online, where so many of us spend so much time. We wake to notifications designed to trigger immediate engagement. We descend through our feeds, each swipe taking us deeper into a carefully engineered maze of want. One video leads to another, as the algorithm serves up exactly the right mix of outrage and affirmation to keep us clicking. Leaving us not satisfied but rather vaguely anxious, as if we have eaten something that looked like food but contained no nutrition.

It’s a hedonic treadmill with an algorithm for a trainer—one that studies our every response, learns our weaknesses, and adjusts its pace to keep us running but never arriving. The feeds are infinite, bottomless—there is no final satisfaction, no moment of completion, only the promise of one more thing that might finally be enough. The more sophisticated these systems become, the more precisely they can trigger our ancient reward circuits, hijacking desires that once helped us survive and turning them into vectors for profit.

We feel the effects in our own lives: the anxiety of endless comparison, the hollowness after another binge of content or consumption, the sense that we’re always behind, always lacking. We feel it in our communities too: conversations fractured by outrage, attention siphoned from the slow work of democracy, shared projects abandoned for private pleasures that don’t quite satisfy.

Without something like Beatrice 2.0, we risk becoming exactly what the attention merchants hope: perpetually dissatisfied consumers, refreshing our feeds in search of something we can’t quite name, having forgotten that what we’re seeking can’t be delivered by any algorithm.

Some traditions would advise us to suppress desire altogether—to mistrust it, to renounce it. There is wisdom in temperance, and a certain freedom in stoic restraint. But I do not think most of us want merely to want less. I for one don’t wish to deaden desire. I want to want well—to long for things that, when pursued, become part of a good life with good friends. The challenge, then, is not to escape desire but to educate it.

Some will say the answer is to unplug, to flee the digital thicket altogether. And it is true: most of us would do well to step away from our screens more often. Yet the modern reality is that much of our lives will remain online. These tools are not going away, and they can even serve as vessels of wonder if we learn to use them rightly. The task, then, is not only to limit exposure but to cultivate habits of mind that let us thrive while plugged in—to educate our desires so that even in digital spaces we can seek what nourishes rather than what corrodes.

That is where Dante’s image of Beatrice still matters. Not because we need a literal heavenly muse, but because we need something like what she embodied: a love that draws us upward, that directs our attention to what is noble and beautiful, that keeps us from mistaking momentary stimulation for real nourishment. In our own age, we might call this a Beatrice 2.0: a cultivated love of beauty that can resist exploitation and reorient desire toward flourishing.

By “beauty,” I do not mean prettiness or decoration, much less the possession of cultural capital that marks one as refined. I mean something far more democratic and capacious. Beauty is what awakens awe, what points beyond itself to deeper meaning, what invites us into shared wonder. It is found in music and mathematics, in basketball as well as ballet, in the sight of a baby smiling or a sunset over water. Three qualities distinguish the kind of beauty I mean from mere stimulation or entertainment:

First, it evokes awe—that distinctive mix of vastness and accommodation that makes us feel both small and expanded. When we encounter genuine beauty, we don’t just consume it; we’re arrested by it, changed by it.

Second, it points beyond itself. A beautiful mathematical proof doesn’t just solve a problem; it reveals an underlying order. A beautiful piece of music doesn’t just please the ear; it expresses something otherwise inexpressible. Beauty is not self-contained but indexical—it points to meaning.

Third, beauty creates fellowship. When we’re moved by beauty together—watching a sunset, listening to music, witnessing athletic grace—we’re bound not by agreement or contract but by shared wonder. Beauty can invite, create, and sustain community.

Can’t social media itself be a source of beauty? Yes, it can. I once had TikTok post about a Sappho poem once reached 16,000 people—16,000 souls the algorithm somehow thought might to hear a bit of Ancient Greek verse. The tools aren’t inherently evil; the question is who guides us in using them. When we approach these platforms with a cultivated love of beauty—we can use them to share wonder rather than manufacture envy. We can let Beatrice, not Elon or Mark, be our guide through the digital realm. The algorithm will still try to hijack our attention, but we can learn to direct that attention toward what nourishes rather than what merely stimulates.

The love of beauty—what the Greeks called philokalia—is not a luxury for peaceful times. It is urgently practical. When our desires are under constant manipulation, beauty offers a different orientation. When we’re told that value means market value, beauty insists otherwise. When we’re isolated in our private feeds, beauty creates genuine connection.

Nor is this an elitist or ivory tower idea. What is elitist is the implicit claim that only rich folks need or can benefit from the orientation and elevation that a love of varied forms of beauty might offer. What is the elitist is the idea that the highest human goods and aspirations are only for some, while the rest should content themselves with being efficient units of production.

Philosophical reflection on beauty rarely finds its way into public policy debates. Yet it can and should. Nicolas Cornell, for example, has argued that even well-intentioned government nudges, meant to guide our choices, should be judged partly by their aesthetic costs. His claim is that when our perceptual environment is cluttered, polluted, or manipulated, our very capacity for beauty—and with it our freedom of thought—can be diminished. To take aesthetics seriously in law and regulation is to recognize that beauty sustains us not only in private life but in public life as well, and that its preservation belongs within the domain of justice

There is another gift that a cultivated love of beauty can offer. Beauty not only directs our desires toward what nourishes; it steadies us when we must face what is not beautiful. As I’ve noted in recent essays, we should face rather than hide from the cruelties and injustices of our world, especially those in which we are indirectly complicit. But that can be it is as difficult as it is vital. And philokalia can help. A life open to awe is a life better able to endure dismay. To glimpse something beautiful—whether in music, mathematics, sports, craft, or even in museum—is to be reminded that the world holds more than its cruelties. The sight does not erase the horrors, but it helps us face them without despair. In this way, beauty becomes not a form of escape but a source of courage. By learning to see and love beauty we might cultivate a reservoir of strength to draw upon when we would otherwise be tempted to look away from what must be seen.

This would not be the first time beauty has been enlisted against dehumanization. The enslaved people who created spirituals, the workers who built libraries and concert halls even while struggling to survive, the civil rights marchers who sang as they faced violence—all understood that beauty is not separate from justice but essential to it. It insists on our full humanity when others would reduce us to mere labor or mere appetite.

Recent research in neuroscience and psychology confirms what poets have long known: encounters with beauty—whether in nature, art, or mathematics—produce measurable benefits. They reduce stress and inflammation, increase generosity and cooperation, enhance creative problem-solving. People who regularly experience awe show less materialism, less narcissism, more concern for others and for the common good.

And beyond these individual benefits is a public one. A democracy whose citizens love beauty may be harder to manipulate than one whose citizens merely chase pleasure or flee from fear. A community bound by shared wonder may stronger than one held together only by economic exchange or shared xenophobia.

At least three questions follow from this diagnosis, all of which will await future essays: First, what hinders us? In particular, what habits of mind prevent us from being guided and enriched by beauty. Second, how can cultivate a responsible love of beauty—an aesthetic phronesis that will allow us to be inspired but remain grounded. And finally, if beauty is key to human thriving, how do we ensure everyone has access to it?

But before we can address either the practical or political dimensions, we should at least recognize the possibility—the hope. We can continue to let our desires be shaped by those who profit from our dissatisfaction. Or we can seek out different guides—not to escape desire but to educate it, not to want less but to want better. The image of Beatrice reminds us that desire can be a teacher if we let it point us toward what truly nourishes. In our age of algorithmic manipulation, we need our own Beatrice—not a person but a practice, not a muse but a method. There may be a way out of our dark wood, if we can together cultivate a love of beauty strong enough to resist exploitation, deep enough to satisfy our hunger for meaning, and wide enough to include us all.