by Laurie Sheck

1.

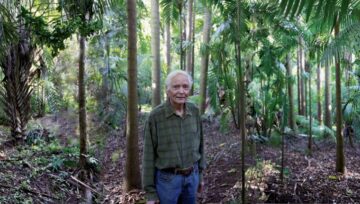

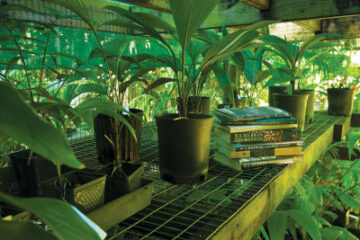

In the garden of the Maui home where the poet W.S. Merwin lived for the last forty years of his life, writing and translating poems, and restoring deforested land into a flourishing palm forest, there is a black stone marker engraved with his name and that of his wife, along with the four simple words “Here we were happy.” It is a remarkable story. Merwin first came to the island in 1975 to study with the Buddhist teacher Robert Aitken. Drawn to the land, he found at first three acres of a disused pineapple plantation where, with the help of friends, he built a house. Later, he purchased and tended fifteen acres more. Over the years, seedling by seedling, he planted his palm forest. At first, he wanted to plant only trees native to the island but found through experience the ecosystem had been so degraded they could no longer survive. The first 800 trees he planted died. After that, he focused on planting various endangered species of plants and trees. He planted one tree almost daily; by the time of his death, he had planted approximately 14,000 palm trees.

The history of the island is one of natural beauty severely harmed by human intervention. When the earliest settlers arrived, many of its trees were cut down to provide wood for the construction of whaling ships. Soon the land was further cleared for grazing cattle. Rats, mosquitoes and other life-forms foreign to the island were introduced. In 1876, the Hamakua Ditch Company began building a network of ditches and tunnels that diverted the rainwater from the central valley to newly cultivated sugar cane fields. The valley was starved of water. By 1917 nearly 130,000 acres of Maui had come under the ownership of sugar plantations and factories. Large numbers of the native population had died from infectious diseases brought to the island by Americans and Europeans. When the pineapple industry arrived, it further destroyed what was left of the native ecosystem.

2.

These are some of the life-forms that were lost: Acacia palm trees, sandalwood trees, many kinds of native land snails, damselflies, honeycreepers.

By the time of Merwin’s death, his plantings included 128 genera and 486 species. One ecosystem had been destroyed but another had begun to flourish.

3.

I first came upon Merwin’s poems in my early twenties. It interested me that he had turned from the lapidary early poems that drew notice from W.H. Auden, who picked Merwin’s first book for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, to something much starker, stripped down, alert to and pained by human hubris and error. By his 6th volume, The Lice, he had dropped punctuation. The poems were concerned with war, destruction, power, and the counterforces that make us of value as a species, and that make our planet a wondrous place. The speaker listens and watches deeply; each word matters and is held to account. If an early poem could sound like this, “By day she walked in the espaliered garden/Among pheasants and clear flowers”, by the time he was in his late thirties, in the poem For A Coming Extinction, he sounded like this: “Gray whale/Now that we are sending you to The End/That great god/Tell him/That we who follow you invented forgiveness/And forgive nothing”.

Such a change is both linguistic and spiritual. Or to put it another way, the change that occurs embodies the way in which the linguistic and spiritual are inseparable.

The Lice is haunted by the Vietnam War. In The Asians Are Dying, he writes, “When the forests have been destroyed, their darkness remains/The ash the great walker follows the possessors/Forever/ Nothing they will come to is real” and “Rain falls onto the open eyes of the dead/Again and again with its pointless sound/When the moon finds them they are the color of everything”.

There is an eerie chill to these poems, but always informing them is a sense of wonder and awe that, even when threatened, asserts itself and cannot be extinguished. I am not the only person who has found they have memorized certain of Merwin’s poems without even really trying. There is a stark integrity and rightness to the language that arrives like a kind of neural shock and embeds itself as a visceral event. One such poem is For the Anniversary of My Death:

Every year without knowing it I have passed the day

When the last fires will wave to me

And the silence will set out

Tireless traveler

Like the beam from a lightless star

Then I will no longer

Find myself in life as in a strange garment

Surprised at the earth

And the love of one woman

And the shamelessness of men

As today writing after three days of rain

Hearing the wren sing and the falling cease

And bowing not knowing to what

Before reading Merwin’s poem, I’m not sure I ever gave much thought to the idea of coming upon each year the day that would one day become my death-day or coming upon the future death-day of those I love; the idea that each year I was passing it without knowing. But ever since reading his poem, I think about it several times a year. The poem simply presents something true, without flourish, like a hand opening, saying: here. So, too, these final lines of his poem, Air, from his volume The Moving Target, the book that first hints at the direction his work is moving toward: “This must be what I wanted to be doing,/Walking at night between the two deserts/Singing.” When I think of Merwin, those lines always come back. The solitary walker, open, alert, appreciative, singing.

5.

Throughout Merwin’s life, his political commitments and his commitment to the natural world were all of a piece. Upon being awarded the 1971 Pulitzer Prize in poetry (he won it again in 2009) he wrote this to the Pulitzer Board:

“After years of the news from Southeast Asia, and the commentary from Washington, I am too conscious of being an American to accept public congratulation with good grace, or to welcome it except as an occasion for expressing openly a shame which many Americans feel, day after day, helplessly and in silence.

I want the prize money to be equally divided between Alan Blanchard, a painter who was blinded by a police weapon in California while he was watching American events from a roof, at a distance—and the Draft Resistance.” Auden publicly criticized him for taking this stand.

Similarly, in the November 19, 1970 issue of the New York Review of Books, he published a statement he made before reading his poems at the State University of New York at Buffalo, explaining why he did not receive payment for his visit there, as in order to do so he was required to sign a form “pursuant to Section 3002, Education Law, State of New York” that demanded he sign a loyalty oath. This he would not do.

To Merwin, whose loyalty was to truth and the precision of language, and to the idea of the poet as an independent being committed to the needs and requirements of his calling, such an oath was insupportable.

6.

Throughout his poems, the engagement with words as things, as both the embodiment of an idea and at the same time palpable beings, comes up again and again. The act of utterance, the body of the word itself, is felt, experienced, challenged, in ways both familiar and strange. Words are untamable, inexhaustible but also creatures of time and place. They are objects to be reckoned with that appear amid the greater silence and sounds of the natural world.

Here is just a sample of some of the many appearances of the word “word” in his poems:

what are you doing here/at the end of the world/words far from the tree before/he had words for anything/long before he wrote/of the hermit crab and tears/with no word for them When the words had all been used/for other things/we saw the first day begin let my words find their own/places in the silence after the animals and even now when I can no longer see/I continue to arrive at words while the sound of the words clawed at him with the words going out like the cells of a brain many of the things the words were about no longer exist

And always in the poems there is silence. The white space the words rise from, the white space that is the silence they only briefly touch. The silence that goes on without them.

7.

In the late poem, The Black Virgin, Merwin writes, “you are not/part of pride or owning”. It is this quality of givenness apart from the built world and the world of commerce, power, technology, that resonates throughout his poems in the figures of trees, wind, dogs, animals, insects, rain. But even as his work is replete with these presences, the realities of our commercial and political world haunt them, like a ghost standing behind. At times there are direct references: “Well they cut everything because why not./Everything was theirs because they thought so.” (The Last One); “An airport is nowhere/which is not something/generally noticed… you sit there in the smell/of what passes for food/breathing what is called air” (Neither Here Nor There); “did you pay by check or by credit card/is this car rented by the day or week… are you getting your money’s worth… do you think there is a future in pineapple (Questions to Tourists Stopped by a Pineapple Field).

His poems are haunted by the question of what it means to be human in the world we are part of.

In his closing talk at the Library of Congress as Poet Laureate and again in the film Even Though the Whole World is Burning, he stresses what he sees as the quality that makes human beings a distinct and worthwhile species:

“Really the thing that makes us so remarkable as a species is not our technology and how smart we are… but the imagination, and we don’t know where it comes from but it’s the ability to care about the whales in the Pacific that are dying from pollution and malnutrition, and the homeless people on the street, and the people starving to death and mistreated in Darfur, in Africa…. It’s the imagination that says they have everything to do with us.”

It is the imagination that makes possible compassion and empathy. The imagination that envisions forests where forests have been destroyed and words where there has been no way of saying.

8.

This treasuring of the imagination also informs Merwin’s vast work in translation. As he pointed out, translation is a significant factor in what enabled 20th century American poetry to come so strikingly into its own. From Pound’s translations, especially his groundbreaking The River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter by Li Po where he found a plain idiom that showed the beauty of a direct, unflowery language, to translations by Robert Bly, James Wright, and others, the American language grew by being exposed to other cultures and ways of seeing. Although Merwin was fluent in Spanish and French, he collaborated with many others to translate work from Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Greek, German, and Russian, among others. It is interesting and moving to see how the poems he chose would have helped to open and deepen his own practice.

Here are a few of his translations from the Japanese poet, Yosa Buson (1716-1783):

In vain I listen

for the voice of the cuckoo

in the sky above the capital

*

This evening I cut

a peony stem

and felt my own spirit wither

*

A peony appears

in my mind

after the petals have fallen

And here is a stanza from the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam who was arrested and died under Stalin:

Quietly, quietly warships are gliding

through faded water,

and in the canals gaunt as pencils

under the ice the leads go on blackening.

The resonance in these translations with Merwin’s own poems and sensibility comes through clearly.

9.

Sometimes, going back to Merwin’s poems, I miss the many new words and images our age has brought us. But that’s not what his project was about. To locate the human within, not apart from the vast natural world, to seek a sense of proportion and humility in our human presence on the planet and how we relate to it, to listen, to learn, to plant, to tend to the integrity and precision of language, this is what his poems engage with. As he wrote in his final book, Garden Time, in a poem he dictated to his wife when he had lost most of his eyesight:

One at a time the drops find their own leaves

then others follow as the story spreads

they arrive unseen among the walking doves

who answer from the sleep of the valley

there is no other voice or other time