by Carol A Westbrook

This is the story of a young man who, to protect the health of his family and neighbors, dared to take on the town, county, state, and federal government, the US Dept. of the Interior, the Environmental Protection Agency, and even the Sierra Club. And he won.

It was 1985. Recently divorced, Rick (that was his name), had custody of his two young children for the three summer months. When the marital home was sold, he promised the children a new home that was better than the previous one; they were delighted when he bought a new beach home on top of a tall sand dune, on the shores of Lake Michigan, near the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, which would eventually become the Indiana Dunes National Park. Both operated under the auspices of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Rick’s house was located in the town of Beverly Shores, Indiana. Beverly Shores began as a resort community planned in1927 by real estate developer Frederick Bartlett of Chicago, but the Great Depression hampered development. The lack of municipal water and sewer systems also contributed to the Town’s slow development. Rick’s new home, as did all the other homes in Town, relied on a well for its potable water supply, and on a septic system to purify waste water before discharging it deep into the ground. National building codes specified how these two facilities were to be constructed and maintained, in what type of soil they could be located, and how far apart septics needed to be sited from wells in order to prevent cross-contamination. The well water was pure and free from contamination so long as the codes were meticulously followed, in particular that septics were sited in dry soil and discharged a safe distance from the wells.

Initially, the Town of Beverly Shores was a collection of inexpensive, small, wooden cottages that housed people with independent income such as artists. In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, building began to include larger and more architecturally interesting homes, no doubt stimulated by the stunning surroundings and spectacular views over the lake. About half were sold as vacation homes, and the rest to permanent residents, of which Rick’s home was one. The majority of home buyers came from nearby Chicago; even today, about half of the 600 residents live in Town on a full-time basis and the remainder use their Beverly Shores house as a vacation home.

From the get-go, Beverly Shores was a center of controversy. It was located in one of the most beautiful and unique ecosystems of the US. In addition to the pristine sandy beaches and towering dunes, it hosts rare plants such as the striking Blue Lobelia and the Eastern Fringed Prairie Orchid. The co-existence of plants native to both the northern and southern US is unique for any location in the U.S. Over 270 species of migratory birds can be viewed in the spring as they make their way up from the south. Nature lovers considered the Indiana Dunes to be a treasure that must be preserved. Ironically, the dunes were initially considered to be valueless land, as they were not arable, and buildings located on the shifting sands could be unstable. This “worthless” land was acquired cheaply by large factories, such as he mills of US steel, or warehouses and harbors.

By the 1950’s it was clear that this unique ecosystem would soon disappear unless action was taken to preserve the remaining dunes. In the 1950’s, the Save the Dunes Council was founded with an eye toward halting development and returning this ecosystem to its natural state. The Council played a critical role in helping to establish the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, which later became the Indiana Dunes National Park. To obtain land, the National Park purchased the parcels it desired through eminent domain. The most common arrangement was the “lease-back,” in which the purchased property was leased back to the previous owner at a low rent for 18 years or until 2010 whichever came first. At the end of the contract the home would be demolished and the natural setting restored. These arrangements were financially very favorable to the seller, but the owner of the property had no choice, and could not refuse to sell if the federal government exerted their power of eminent domain.

The residents of the Town were split in their support of the National Lakeshore; many wanted to remain intact as a Town while others wanted to take the deal. The Save the Dunes Council would have liked the entire town be to incorporated into the National Lakeshore, while many did not want to leave, especially those of the newer homes. The Red Lantern Inn and restaurant was on a premier lake shore location and was purchased as a leaseback by the National Lakeshore; their lease was due to end in 1986, at the time of this story. This lucrative business was in the process of negotiating for an extension of the lease, which was likely to be approved, because it was a big draw for Lakeshore visitors, helping to maintain a high visitor count, which was vital to the success of the National Lakeshore.

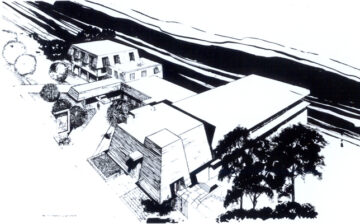

The Red Lantern was a local landmark, and the Town residents wanted it to remain open whether they were pro-park or anti-park. A resort and restaurant had operated on this site since the 1930’s, and in 1968 it was purchased by the Larson brothers. The location was stunning; you could sit and eat a meal watching either the sunrise or the sunset. The Larson’s employed local highschoolers for the summer; the local chapter of the Sierra Club met there, as did the Save The Dunes Council. Banquet rooms were rented for weddings, birthdays and other festivities. Most importantly, there was plenty of parking in a lot across Lake Front Drive (which was immediately across the street from Rick’s dune.) Nobody wanted the closed, least of all Dale Enquist, the head of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Although he had plans for a lakefront facility for park visitors in this location, that would be in the far distant future. For now, keeping it open would help to maintain good relations between the Town and the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

In July of 1985, Rick’s two young kids came out for the first weekend of their summer, and spent the next 2 delightful days on the beach playing in the water, building sandcastles and meeting their neighbors. On Monday, the National Lake Shore had posted signs on the beach across from Rick’s house: no swimming, water polluted. The family had to walk about a quarter mile to the next beach, which did not have a high bacterial count. The contaminating bacteria were primarily coliforms. Coliforms reside in the human intestine, and their presence in the water meant likely contamination by human waste, toilets, or septic effluent. Exposure to fecal contamination can lead to a variety of serious illnesses, including salmonella, dysentery, diarrhea, infectious e. coli, cholera, typhoid, hepatitis A and hepatitis B. Keeping coliform counts low in drinking and swimming water is one of the most important principles of public health.

Fortunately, come Friday the signs had been removed and the beach was open for the weekend crowds. But sure enough, the “no swimming–water polluted” signs went up again on Monday. This pattern repeated again, frustrating Rick and his neighbors, many of whom felt cynically that taking the signs down on Friday allowed the National Lakeshore to keep their visitor count high.

Although everyone complained about the lake pollution which had been going on for the last 3 years concurrent with record high lake levels, no one felt obliged to do anything about it. So Rick got together a number of nearby residents who were most affected by the closures. It was a good opportunity to meet his new neighbors and perhaps resolve the pollution problem. Although small lakes and pools can become contaminated if there are many swimmers, this is unlikely in a lake as big as Lake Michigan with its many currents. The group agreed that the coliform contamination must be coming from a septic system that was flooded due to the high water table resulting from the high lake level. But which septics? Flooded homeowners’ septic systems could contribute, especially as the water table was very high that year and some residential systems might be flooded. Again, the number would be insignificant compared to the vast size of the lake. The most likely possibility was The Red Lantern’s septic system, particularly as the coliform contamination centered at its nearby beaches. Perhaps it had a septic system that was not functioning properly because it was saturated or “under water” due to the high lake level.

Although everyone complained about the lake pollution which had been going on for the last 3 years concurrent with record high lake levels, no one felt obliged to do anything about it. So Rick got together a number of nearby residents who were most affected by the closures. It was a good opportunity to meet his new neighbors and perhaps resolve the pollution problem. Although small lakes and pools can become contaminated if there are many swimmers, this is unlikely in a lake as big as Lake Michigan with its many currents. The group agreed that the coliform contamination must be coming from a septic system that was flooded due to the high water table resulting from the high lake level. But which septics? Flooded homeowners’ septic systems could contribute, especially as the water table was very high that year and some residential systems might be flooded. Again, the number would be insignificant compared to the vast size of the lake. The most likely possibility was The Red Lantern’s septic system, particularly as the coliform contamination centered at its nearby beaches. Perhaps it had a septic system that was not functioning properly because it was saturated or “under water” due to the high lake level.

A septic system is a passive method for purifying waste water, which removes bacteria and contaminants by allowing the water to slowly percolate through the soil, during which time the contaminants decompose due to the action of soil bacteria. The water then returns to the aquifer (the ground water) in a highly purified state. An effective septic requires a significant stretch of dry soil through which the waste water must travel before reaching he aquifer. When the ground water level is high the purification process is incomplete, and contaminated water will reach the aquifer; the septic is said to be saturated. That was the presumed problem with the Red Lantern’s septic system, which allowed coliform bacteria to spill out into the lake, especially as it treated a high volume of sewage resulting from its large number of customers.

As proof that the Red Lantern’s septic was the source of the lake pollution, members of this group recalled an incident with a neighbor, a dentist, who wanted to test this theory. To do this, he went into the Red Lantern’s rest room and flushed a quantity of concentrated methylene blue into the toilet. Methylene blue is the dye dentists use to detect caries and fractures in teeth. Needless to say, shortly after flushing the dye it appeared in the lake adjacent to the restaurant. He repeated the experiment 3 times, and the conclusion did not change. As this information was disseminated throughout the town, it became clear that the Red Lantern was the source of the high coliform count in Broadway Beach, adjacent to the restaurant, and in the adjoining town beach, because the Lantern’s septic system was under water. Although everybody hoped the Red Lantern would remain in business, nobody wished this at the expense of the Town’s health. Rick, in particular, wanted to stop this pollution before one of his kids caught something dreadful. In the early summer, Rick himself had had a fever and cough which lasted several days, shortly after swimming in the lake.

The general consensus was that if the Red Lantern’s septic was under water, it would have to be relocated to a dry area. Furthermore, this would require following the newer national plumbing codes which, for a commercial septic, would require a large leaching field. The obvious location for this field would be the lot that the Red Lantern was currently renting from a private owner for its parking lot. This field was across Broadway from Rick’s house, and across Lake Front Drive from the Red Lantern; the Lantern was diagonally across from Rick’s lot. The sewage would have to reach this field by a pipe which would cross the street underground; the Town would have to grant a variance to allow the pipe to cross the road, which would likely be granted. Using the current parking lot for the new septic field seemed an ideal solution, and Dale Enquist, the Superintendent of the Park, favored this solution, as it could be implemented quickly and would solve the problem of contaminated beach water once and for all.

However, the plumbing codes require that the leaching field not have any structures or roads on it, and so it could no longer be used as the parking lot for the Red Lantern. If this design of the septic system were used, it is likely that the State Board of Health would not certify the septic system as safe unless the parking lot were elsewhere. But a nearby parking lot was critical for the business success of the restaurant. Furthermore, a number of residents, including Rick, had wells that were 100 feet or less from the proposed leaching field, and were at risk of contamination of their wells, given the large volume of sewage that would be pumped daily into the field.

Rick’s next step was to take this problem to the Beverly Shores Town Council, the governing body of the town. As he explained in a letter to the council, he was a licensed professional engineer, and well qualified to evaluate this problem and propose alternative solutions. In a letter dated May 3,1986, he listed four ways to deal with the Red Lantern’s sewage problem that would avoid frequent closing of the town beaches and contaminating the water supply.

- Eliminate the contamination by closing the Red Lantern

- Reduce the amount of sewage to levels that can be safely handled by a non-pressure manifolded system, by serving fewer customers. In other words, sharply reduce the seating capacity of the Lantern and eliminate the large banquet crowds.

- Pipe the effluent to uninhabited areas to the west or southwest of the Lantern, [instead of the parking lot.] The National Park lands might be appropriate since the Lantern is a federal leaseholder and apparently Park Superintendant Enquist wants to approve their lease extension.

- Use a system of closed pumped holding tanks.

Mr. Enquist, as superintendant of the National Lakeshore, favored using the parking lot as a leaching field. (He was apparently unaware that the National Codes did not allow this). He stated that “the system meets state requirements for separation of commercial septic systems from adjacent residential property and wells [100 ft] …and we do not feel that your well or any other wells in the area will be contaminated.” On the contrary, Rick and his colleagues felt that this separation was inadequate, and preferred that the National Lakeshore offer a plot of land to be used as a leaching field that was further removed from the restaurant and from other resident’s wells. At this point it was clear that that the Town’s (and the National lakeshore’s) interests in keeping the Red Lantern open were at odds with the interests of Rick and a half dozen citizens of the Town who did not wish to contaminate their water supply.

Rick continued his letter-writing campaign, appealing to all individuals and institutions that might have an interest in this problem, or that might be able to help. Rick contacted the Sierra Club and the Save the Dunes Council—who continued to hold their monthly meetings at the Red Lantern; neither organization wanted to get involved, in spite of the fact that both were committed to preserving the natural state of the Indiana Dunes, and the Lantern was flagrantly polluting the lake.

Rick wrote to the county board of health, who admitted they had no jurisdiction over the National Lakeshore, which was an arm of the Department of the Interior. He wrote to Valdas V. Adamkus, regional administrator for the EPA. The EPA operates as an agency within the executive branch, responsible for enforcing environmental laws and setting national pollution-control standards. Adamkus claimed that he had no jurisdiction over the National Lakeshore, which was an agency of the Department of the Interior. (Interestingly Mr. Adamkus, an immigrant from Lithuania, and a naturalized citizen of the US, was later elected president of Lithuania). So far, Rick was unable to find anyone to take his side; he realized that the only group who had authority to intervene over a federal agency was Congress.

Finally, in a Hail Mary attempt, Rick wrote to Indiana’s two senators, Richard Lugar and Dan Quayle, “Please do what you can to stop the renewal of the (Red Lantern’s) lease.” As members of Congress, the senators had the power to persuade the Department of the Interior to intervene. Throughout the next few months Rick kept the senators apprised of the situation as it developed.

The summer dragged on and the coliform contamination continued unabated. The newsletter of the Association of Beverly Shores Residents, reported the coliform counts. For example, on August 5, the beach at Central Avenue, 34; Broadway Beach, 394; Red Lantern East, 1510; Red Lantern West, 1100; State Park Road 6. (Counts more than 400 are considered hazardous for swimming.) The reports clearly showed a peak of hazardous coliform counts centering at the beaches surrounding the Red Lantern. By this time, most of the residents of the Town were aware of the problem. The majority of residents, along with the Park Superintendent, Dale Enquist, favored moving the septic system to the Red Lantern’s parking lot; a vocal minority of about a dozen residents, including Rick, disapproved of this solution, which was likely to poison their wells with incompletely-treated septic effluent.

This stalemate was resolved when the Red Lantern petitioned for an extension of its leaseback to January 2000, instead of its current December 1986. The extension was justified in that this date is more in line with all the other leasebacks in the National Lakeshore area. The Larson brothers, the owners of the restaurant, were anxious to continue the lucrative business for as long as possible. As a condition of this renewal, Mr. Enquist required that the Lantern install a commercial septic system that would handle the amount of septic effluent produced by the restaurant, approximately, 7,000 gallons per day. He also required that the Larsons keep up the property and bring it to current standards—that meant a new roof, new carpeting, an additional emergency exit, and so on.

Adding these new provisions to the leaseback requirements was a clever move on behalf of Mr. Enquist, as it gave the appearance that he was in favor of supporting the Red Lantern, while he knew the upkeep requirements would make it too expensive for the restaurant to continue, and they would likely have to close. Rick always suspected that the Senators pressured Mr. Enquist to find a way to close the Red Lantern. As Senator Lugar wrote to Rick, “Responding to the concerns of individual Hoosiers in dealing with the federal government remains an important part of my work as a U.S. Senator.” Congress had power over the Dept. of the Interior, and the two senators from Indiana chose to wield it.

The Indiana Dept. of Public Health reviewed the Larson’s plans for the septic and found it acceptable. Yet to implement these plans as well as the required building renovation would require an investment of $200,000, or over a half million in today’s dollars. “Those costs would be a wasted investment” Ken Larson told the Michigan City Post Dispatch on Oct 4, 1986, “because when the current lease agreement expires in 1999 it won’t be renewed. The National Park Service plans to knock down all the buildings on the Lake by 1999,” he said, “Why stick around?”

And indeed they didn’t stick around, though Kenny, one of the two Larson brothers, pursuing his dream of running a restaurant, opened Hammers Food & Drink in nearby Michigan City. Hammers was a popular restaurant, though it never had the cachet that the Red Lantern did. It stayed open until its losses due to Covid forced it to close on March 30, 2024.

The Red Lantern Inn closed its doors for the final time on Saturday, October 4, 1986.The closure of the Red Lantern cleaned up the lake pollution and prevented contamination of nearby wells. Furthermore, it gave Mr. Enquist the opportunity to build the Lake View facility, a welcoming entrance to the now-pristine sand beaches of what is now the 61st national park, the Indiana Dunes National Park, established in 2019. Rick managed to turn the tides by enlisting the aid of the Senators to challenge the federal government, and the result was a win-win for everyone.

As you may already know, Rick Rikoski is my husband, though I did not know him at the time of this story. He was so inspired by this experience that he continued to play a role in the political life of Beverly Shores, serving on the Town Council for 24 years. During that time, he led a number of initiatives that included bringing in municipal water to the town’s residents, engaging the Army Corps of Engineers to prevent beach erosion with limestone block revetments, facilitating a compromise between the deer hunters and the deer protectors that would lower the deer population and save the ecosystem, and facilitating the “dark skies” initiative by turning off many of the overhead street lights in town. These initiatives improved the quality of life for the residents of Beverly Shores, a small town that now resides peacefully within the boundaries of the Indiana Dunes National Park.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.