by Bill Murray

At the end of the road, Kirkenes punches above its weight

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

It’s different in the Arctic. Norwegians who live here make their lives amid long cold winters, seasons of all daylight and then all-day darkness, and with a neighbor to the east now an implacable foe.

Finnmark, Norway’s northernmost county, is bigger than Denmark or Estonia, but with a population roughly the size of a suburb in Oslo, the Norwegian capital.

For those of us who don’t live here, the first and biggest difference is that Finnmark is governed by extremes of light and dark. Just now, in the middle of August, the Arctic is leaping and bounding toward darkness. The days are still over eighteen hours long, but losing more than ten minutes of daylight every twenty-four hours.

Many people think near 24 hour summer sunlight must be unbearable; you’d never get any sleep. In fact, all that sun can be handy, not just for outdoor pursuits, but say you want to read a book at two in the morning. Besides, if you must sleep, there are things called blackout curtains.

Winter darkness is a different story. In Kirkenes, the border town and administrative center of 10,000-person Sør-Varanger municipality, when snowflakes have a mind to, you can imagine they come not in flakes but by the dollop. Storms off the Barents Sea can flatten trees and fling sea foam far inland. Winter air can be so crisp it bites.

Flying in, Finnmark presents as a brawny, manly landscape of gneiss and granite, some of which is nearly as old as the oldest continental crust on Earth, meaning something like three billion years.

Kirkenes shares its latitude, 69.7 degrees north, with northern Alaska and central Greenland. Except at 70 degrees north in Canada, for example, the land is tundra, with no continuous trees — only dwarf shrubs and moss. It’s tundra here too, but owing to the North Atlantic Current and the Gulf Stream, where Canada has tundra, Finnmark, in places beyond Kirkenes, has forest.

Trees in the dales evoke something Bryn Thomas wrote in the Trans-Siberian Handbook about the Russian taiga. On the taiga “It appears as if there is a continuous forest in the distance.”

“However if you walk towards it you will never get there as what you are seeing are clumps of birches and aspen trees that are spaced several kilometers apart. The lack of landmarks in this area has claimed hundreds of lives.”

That may be true in the Russian taiga, but these northlands have been more thoroughly staked out by indigenous reindeer herders, the Sami. A drive down the appropriately named Langfjorden (‘long fjord’) outside town shows how apparent trade routes are in winter, tracing the long fingers of frozen lakes that act as highways.

Replace the taiga’s birches and aspen trees with berries, lichen and mosses (and birch, pine and spruce in valleys) and you have Finnmark. And just look around! There is nothing but room.

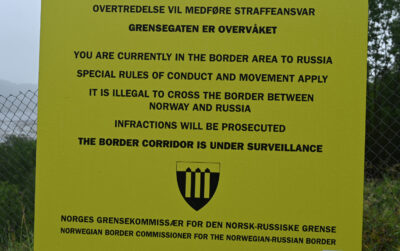

Such an expanse might suggest freedom. But walk ten kilometers straight east from Kirkenes and you reach the end of the continent-wide area of free travel called the Schengen Zone. There you find a hostile border.

Norway is the third place I’ve written from for 3QD this year about Russian relations with countries around the former Soviet border—the previous two were Moldova and Estonia.

The three countries’ interactions with Russia are all very different, and the differences illuminate the challenges facing Vladimir Putin all across his periphery. From his point of view the Soviet collapse really must look like, as he put it, the “biggest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.”

Consider:

• Former Soviet Moldova lives in fear of Russian hybrid warfare, with a very small economy, little money, few military resources, and without the institutional backing of either NATO or the European Union. Its only borders are with Romania and Ukraine. To Chișinău, Russia’s war on Ukraine is no less existential than it is to Kyiv.

• Former Soviet Estonia is a member of both, but also a relatively poor former Soviet country, and the border city of Narva has a strong cultural affinity with Russia, making it a prime location for future Russian hybrid warfare. Most people in Narva speak Russian as their native tongue.

• Democratic Norway is a rich country wealthy in natural resources. It was a founding member of NATO and holds the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world. It shares warm relations with both its non-Russian neighbors, Finland and Sweden. But the Norway/Russia border is politically, culturally and socially different as night and day, and the people of the region have already experienced Russian hybrid warfare, as we will see.

Some readers will remember the story of Mathias Rust, a 19-year-old West German who flew a Cessna from Helsinki into Red Square in 1987, during Mikhail Gorbachev’s Glasnost era. Bjarge Schwenke Fors, head of department at the Barents Institute of the Arctic University of Norway, shares the story of the fishing vessel Yngvar, that sailed in 1959 “from the coastal town of Vardø in Arctic Norway to Soviet Russia with a bold plan of performing a brass band concert in Murmansk.” Like Rust, it neglected to notify the authorities, and the Yngvar was boarded by the Soviet navy.

Feverish negotiations ensued. In the end (and very unlike the fate of Mathias Rust, who spent about 14 months in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison), officials extended an official welcome and “(t)housands attended the concerts, which were covered by local TV.”

Fors says this individual initiative from below marked the beginning of lasting cultural cooperation across the border, cooperation that more or less completely ended with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Some say regional cooperation began earlier, in World War II, when Norway was occupied by Nazi Germany. Atle Staalesen, Director at the Independent Barents Observer online newspaper observes that “this part of Norway was liberated by the Soviet army in October 1944. And in contrast to many other places, the Soviets, they actually left,” creating a basis for future friendly approaches.

With the coming of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Glasnost and Perestroika in the 1980s, cross border relations were poised for change. In 1993 a formal intergovernmental framework, the Barents Cooperation, was established in Kirkenes to promote peace, stability, sustainable development, and cross-border cooperation in the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and northwest Russia.

Between Kirkenes, maybe twenty minutes from the border, and Nikel, maybe the same distance on the other side, and the nearby town of Zapolyarny, cultural differences are stark and enduring.

But once cooperation became possible, Kirkenes went all in. Reveling in the novelty, Norwegians would go to the Russian border town of Nikel for a Friday beer. Petrol was cheaper in Russia. Car repair, too. Russians visited Kirkenes for food, clothing, other things. It was fun.

Kirkenes presented itself as a “Barents capital,” a bridge between Norway and Russia, even pointedly displayed a few road signs in the Russian Cyrillic script. But in 2014 Russia took Crimea.

Then, says Staalesen, “in the fall 2015 suddenly there were big numbers of refugees coming across the border, and during that fall the total number was about 5,000.”

The Russian FSB, the Federal Security Service, strictly controls its side of the border, where it’s next to impossible (and dangerous) for unauthorized people to move about. Crossing the border on foot is not allowed, but that fall, great numbers of bicycles suddenly appeared—in a remote corner of the Arctic—for ‘refugees’ to ride across the border.

Staalesen calls it Russian FSB-sponsored hybrid warfare, and says it worked. Local authorities were not prepared, and it created chaos on this side of the border.

From Oslo’s corridors of power, Kirkenes must seem far away. It is far away—Google Maps estimates that if we set off down the E6 from Kirkenes via the fastest route, through Sweden, we’d arrive in Oslo somewhat more than 22 hours later.

And Kirkenes is so tiny, just 4,500 people, so few Norwegians living way up here by themselves. But while national politics may seem far away, in getting Oslo’s attention, Kirkenes, punches above its weight.

Anne Figenschou, an advisor at the Barents Institute, thinks Oslo makes a specific effort “to put us in focus, to highlight that we are important, that we have this kind of economical support to survive, because the sanctions (have) been dramatically regarding the economy of this town. Several companies have (had) to shut down.”

More generally, she says, “center and periphery has been an important dimension of politics in Norway. Every government is very much interested in what’s happening in the borderland. With regard to this very area, the area bordering the border, I think it’s not like at the end of the world, they are very much aware of this region in Oslo.”

“Compared to other peripheral places this is not peripheral.”

Bjarge Schwenke Fors says the border region is “an area important in many ways, even symbolically, to show presence. There have been also very close relations between local authorities and national authorities, between here and Oslo, for a long time. Throughout the Cold War and after the Cold War.”

They agree that Kirkenes must be one of the most visited places by ministers in the country. Next week for example, fourteen Norwegian ambassadors will be in town on what travel agents call a fam trip.

Kirkenes punches above its weight in other ways too. Since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russians have been banned from large scale import of expensive champagne. But in the border region individual entrepreneurs have taken up the slack.

A story in the business newspaper E24 (Google translated) reports that “nowhere in the country have more bottles of Dom Pérignon and Cristal been sold this year” than on Norway’s only border with Russia, in tiny little Kirkenes.

Norway and Finland form Europe’s northeastern border with Russia. These days, Finland puts on a brave face about its long Russian border, running 1,340 kilometers south from Norway. The Finns are even a wee bit cocky about their shiny new NATO membership. Norway has historically been more circumspect.

From the Cold War years until not many years ago, Finland and Sweden were officially neutral, leaving Norway militarily isolated in the north. As a result, Norway practiced an intentional demilitarization of its border region as a goodwill gesture toward Moscow, a sort of Finlandization-lite officially called “beroligelsespolitikken” in Norwegian, or “the policy of reassurance.”

From 1949 onward, Norway pledged that no foreign troops or bases would be permanently stationed on its soil in peacetime, it would not station nuclear weapons on its territory and the army kept its main forces well west of the Russian border. Large-scale NATO exercises were always held to the west of Finnmark.

Today, with Norway’s Finnish neighbor in NATO, that policy no longer makes sense, and Norway’s military posture is changing. The military base by the Kirkenes airport, which houses the border guard, for instance, is expanding rapidly.

From Oslo, Finland (like Kirkenes) may seem a long way away. Viewed from the capital, Helsinki is way across the Baltic Sea beyond Sweden. But to Kirkenes, with Finland in NATO and only around 45 kilometers down the road, its neighbor offers an appreciated potential for military cooperation. Finland’s NATO membership has completely changed the security situation for this part of Norway.

If for reasons of history Norway still moves deliberately in militarizing its border, Finland does not. It’s proud of the strength of its formidable stash of F-35s, despite some recent worry about the steadfastness of its American ally, which built them.

The concern is that F-35s depend so much on American software and spare parts that they may be useless if the US withdraws support. Portugal, for example, has decided against F-35s, and Canada is reconsidering.

But in this corner of the Arctic they’ve committed and they’re all in. Norway has flown F-35s for eight years and has ordered 52 more, some of which are bound for Evenes Air Station near Narvik, around 25-40 minutes flying time from the border.

•

Whatever is to come on the Norwegian border with Russia, an almost certainty is the continuation, well into the future, of hybrid warfare. Staalesen, of the Barents Observer, sounds resigned. He thinks that’s a much more likely future than a Russian invasion with soldiers and military hardware.

“There are so many ways to destabilize and make mischief,” he says. “You can tamper with the drinking water, the electricity supply, infrastructure, you can make it very hard to live here. And you can do sabotage to anything, so I think that is a bigger danger than green men here.”

The town of Vardø, three hours’ drive from Kirkenes and around fifty kilometers across the Barents Sea from Russia, is a case in point. It’s home to key components of Arctic intelligence infrastructure, prominent American and Norwegian made radar systems. These have drawn denunciations, and even threatening air maneuvers from Russia.

In March 2017 bombers from airbases on the Kola Peninsula flew over the sea toward the radar installation, adopting offensive profiles before turning back just short of entering Norwegian airspace. In February 2018, eleven Su‑24 fighter‑bombers did much the same.

At the same time, Anne Figenschou, the Barents Institute advisor, says Russia is building an unusual number of ‘memorials’ around Vardø. At least three Russia-initiated WWII memorials went up in the 2010s, two honoring Norwegian partisans who helped the KGB and the Red Army in World War II and another to Soviet pilots who lost their lives during the war.

This push for monuments has apparently been initiated by officials from Murmansk and the Russian Consulate General in Kirkenes.* The monuments, painted Soviet red with Norwegian names in Cyrillic letters, give Russian officials a pretext to be near the radar installations, and the Vardø mayor wants them removed.

Figenschou calls it pure provocation. Fors says it’s not only about intelligence. It is that, but it’s also about symbolically appropriating the landscape, marking it as Russian.

Could it be a future place for little green men? To protect it, to protect Russian interests?

“Could be, I mean, could be, yes, who knows? It’s also a part of the picture up here. That whole gray area of hybrid warfare, creating monuments, creating crosses, symbols of old age heritage, Fors says.

There is a Russian Orthodox church just on the border outside Kirkenes, Borisoglebsk, the Church of Boris and Gleb, on the western shore of the Pasvik river. The highest-ranking Russian Orthodox official on the Kola Peninsula, Metropolitan Mitrofan, visited there earlier this month and declared, “Our souls seek this place.

“We feel its special force, its special divine force…. It is important that we are here, on this very forward position of the border of our country,” Mitrofan said, and called it “a spiritual border that stands against the Evil that is rolling over us.”

Fors notes that there’s a Norwegian church on the border as well, further north, King Oscar the Second chapel, which is also placed, he says, again very performatively, at the very border, to demonstrate Norwegian sovereignty. It’s an old game for both, he says.

For now it appears that events on Norway’s Russian border have come full circle. Staalesen: “Kirkenes, was, pretty much in the Soviet period, the end of the road. It was the border town. Then “for thirty years it was no longer the end of the road, it was a bridge. Now we are back to the end of the road story.”

The border is still open, he says, but few people cross. “The Norwegian relationship to Russia has changed a hundred percent from the past. There is nothing to cooperate with anymore.”

•••••

* The Kirkenes consulate sits across a small square from City Hall in Kirkenes. Whether or not it actually provides consular services seems a bit of a mystery. No one I spoke with was entirely sure. If it does, it is one of only two around the Nordic mainland—the other is in Mariehamn, capital of Åland, an archipelago between Sweden and Finland that is demilitarized by treaty. The Kirkenes consulate was closed in October, 2024, when Norway ordered a reduction of Russian diplomats, but on the day I walked by the Russian flag flew and the garage—motor pool, perhaps—in particular, bustled with activity.

•••••

I write more like this at Common Sense and Whiskey on Substack.

___________________

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.