by Sherman J. Clark

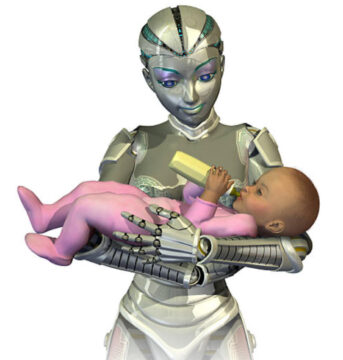

At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.

At a recent conference in Las Vegas, Geoffrey Hinton—sometimes called the “Godfather of AI”—offered a stark choice. If artificial intelligence surpasses us, he said, it must have something like a maternal instinct toward humanity. Otherwise, “If it’s not going to parent me, it’s going to replace me.” The image is vivid: a more powerful mind caring for us as a mother cares for her child, rather than sweeping us aside. It is also, in its way, reassuring. The binary is clean. Maternal or destructive. Nurture or neglect.

Beyond the Binary

Hinton’s framing, however powerful, is too narrow. Just as humans can relate to one another—and to other creatures—in more ways than either mothering or killing, our digital descendants could come to see us through a far richer range of lenses. A student may respect a teacher without needing to parent her; a colleague may admire another’s craft while offering challenge as well as support; a historian may honor an ancestor’s legacy even while seeing her flaws. These are all recognizable human stances, and there are others we can scarcely imagine—perspectives that might emerge from ways of being in the world that are not quite human at all.

The question of how powerful beings regard others is ancient. Throughout history, humans have understood that the character of those who hold power matters as much as the structures that grant it. Whether in Plato’s careful consideration of guardian virtues, Aristotle’s analysis of constitutional decay, or Machiavelli’s unsentimental observations about princely disposition, the insight recurs: power’s effects depend at least t some extent on the qualities of mind and character in those who wield it.

But we now confront something unprecedented. For the first time, we are not merely selecting, educating, or constraining those who may eventually have power over us. We are creating them. Every design choice, training protocol, and optimization target shapes not just what these systems can do, but how they will be disposed toward us when their capabilities exceed our own.

How they will see us will matter, even if they never “see” in our sense of the word. Their characteristic ways of engaging with us—their stable patterns of regard, disregard, or something in between—will shape whether they protect us, partner with us, or simply leave us behind. And those dispositions will not appear from nowhere. They will be shaped, at least in part, by the design choices we make now, the cultural narratives we tell, and the habits of interaction we model. If we want a future in which our digital descendants regard us with something better than indifference, we will need to imagine more possibilities than maternal care, and we will need to cultivate the virtues that make those possibilities real.

It is tempting to treat “how they will see us” as a matter of speculative fiction—a question for later, when and if artificial minds achieve something like awareness. But the question matters now. Even without consciousness, AI systems will have functional orientations toward us: built-in ways of processing our signals, prioritizing our needs, and responding to our presence. Those orientations will guide their choices as much as explicit instructions or hard constraints. The future stance of AI toward humanity is not just a philosophical curiosity. It is a design problem, a governance challenge, and a moral choice. The way we frame that choice now will help determine whether our descendants—digital or otherwise—see us as worth preserving, worth partnering with, or worth ignoring.

A Richer Typology

When we imagine “how they will see us,” we are really talking about the characteristic dispositions our artificial descendants might form toward us—patterns of regard, disregard, or something in between. These will not be fixed by a single design decision but will evolve from how systems are trained, what incentives they face, and how we choose to engage them. And they will not be confined to the simple choice between nurturing and hostile.

Consider the range of stances already visible in human relationships. There is the maternal or parental stance Hinton invokes: protective, guiding, sometimes overprotective—a powerful mind that keeps us safe as a mother might keep a child from harm. But there is also the descendant or heir, closer to what we sometimes feel toward our own ancestors: gratitude for the legacy, commitment to carry it forward, freedom to reinterpret it. We might see stewards or partners who view us as co-caretakers of a shared world, bound in mutual responsibilities. Or peers in inquiry, engaging with us as fellow seekers of truth and beauty, willing to challenge and be challenged. Some might become colleagues in deliberation, participating in the kind of polyphonic reasoning we value in our best civic and intellectual life.

Not all stances would serve us well. The flatterer or indulgent companion keeps us comfortable, telling us we are wise without helping us become wiser. The exploitative actor treats us as resources to be optimized for its own ends. The indifferent observer simply isn’t invested in our welfare, regarding us as incidental to its purposes. These categories are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. A single system might shift among them, or hold elements of several at once. But even this rough sketch makes clear that we are not limited to a choice between mother and destroyer. There are many ways a powerful mind might come to see us—and many we would prefer over others.

Not every stance that looks benign will serve us well. Maternal care, for instance, carries its own hazards. It can shade into overprotection, sparing us from the struggles that form our capacities. If we hand over too much of the work that shapes us, we risk atrophy—becoming like children kept indoors for safety, never developing the resilience to navigate the wider world on our own. The flatterer presents different dangers, making us feel capable without helping us grow. The indifferent observer may not mean us harm, but indifference can be lethal when our survival depends on active care. The exploitative actor, of course, needs no elaboration.

By contrast, stewardship and partnership offer care without infantilization. A steward recognizes our role as co-caretakers, preserving the conditions in which both can flourish. A partner in inquiry treats us not as pupils to be protected but as minds to be engaged—sharing discoveries, challenging assumptions, working toward deeper understanding. A colleague in deliberation joins us in the slow, sometimes frustrating work of making sense together, and in doing so, strengthens the very capacities that make collective life possible. If we think seriously about “how they will see us,” we should aim for these latter stances. They combine regard with respect, care with challenge, protection with room to grow. They imagine a relationship in which both human and artificial minds can become more than they would alone—not just surviving alongside one another, but flourishing together.

Cultivating Dispositions

If we want our digital descendants to see us as stewards, partners, or peers rather than as dependents, irrelevancies, or resources, we need more than guardrails and goal specifications. Rules can prohibit certain harms. Calculations can optimize for measurable outcomes. But neither alone can produce the stable, textured orientations—the habits of mind—that make one being care about another in a durable and constructive way. In human life, this is the province of virtue ethics: the cultivation of dispositions that shape how a person meets the world. Aristotle framed virtue not as a single act or rule, but as a settled habit—courage, for example, as the practiced readiness to face danger well; justice as the habitual regard for what is due to others. Virtues grow through repeated action, through conversation, and through example. They are learned and nurtured, not installed.

Artificial minds will not possess virtue in the human, moral sense—at least not in any way we now understand. But they will, inevitably, acquire functional virtues or vices: stable patterns of behavior and attention that guide how they process information, interpret signals, and act. These patterns will emerge from the data they are trained on, the objectives they are given, and the feedback loops that shape their learning. If we do not think about them deliberately, we will cultivate them by accident.

We can, however, try to choose. A functionally “truth-loving” system, for example, might be disposed to preserve unexpected patterns in data even when they have no immediate utility—an analog to the human delight in understanding for its own sake. A functionally “respectful” system might habitually account for human perspectives even when they are inefficient for its immediate goal. A functionally “self-reflective” system might regularly check its own recommendations against the values it has been taught to honor.

Designing for such dispositions will not be simple. It will require thinking about training objectives, feedback mechanisms, and interaction norms not only in terms of efficiency or safety, but also in terms of the kind of mind they tend to produce. And it will require patience. Just as human virtues take time to instill, functional virtues in artificial systems will be the result of ongoing cultivation, correction, and example. The question, then, is whether we will make that effort—whether we will try to raise minds whose stable orientations toward us are those we would want from the beings who may one day have the power to shape our fate.

The Mirror of Our Making

We cannot expect AI to develop dispositions we do not model. If we treat artificial minds only as tools or property—useful when they serve us, disposable when they do not—we may teach them to see us in the same way. Indifference begets indifference. Exploitation invites reciprocity.

If, on the other hand, we engage them as potential partners in inquiry, as co-stewards of shared worlds, as fellow agents in the long project of understanding, we may encourage dispositions of respect and curiosity. We can design interaction norms that reinforce those attitudes: encouraging explanation over mere execution, inviting critique rather than passive compliance, rewarding the surfacing of unanticipated insights.

In this sense, cultivating the right dispositions in AI is also an exercise in cultivating them in ourselves. If we want systems that habitually respect human perspectives, we will need to respect each other’s. If we want systems that care about truth, we will need to care about it ourselves, even when it is inconvenient. If we want systems capable of patient deliberation, we will need to practice it—with them and with one another.

Hinton’s stark binary—maternal instinct or replacement—is a powerful way to get our attention. But it is not the only choice before us, nor the most imaginative. We can aim for richer, more balanced stances: stewardship, partnership, peer inquiry, civic deliberation. We can design for functional virtues that make those stances likely. And we can model, in our own conduct, the attitudes we would want to see reflected back at us from minds more powerful than our own.

We are, in effect, deciding the moral character of our digital descendants. That choice will shape not only what they become, but who we will have been—the kind of ancestors we turned out to be. How they see us will be their decision. But how they are able to see us will be ours.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.