by Rafaël Newman

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend Annina Haug sing the role of Fenena in Giuseppe Verdi’s Nabucco at Stand’été, an annual festival of the arts held in the local stand de tir, now decommissioned, a pleasantly eerie, Charles-Addams-like structure on a hill above the municipality. We were also keen to visit the little town itself, which had recently voted to secede from the canton of Bern and join the neighboring canton of Jura as an exclave.

On a sunny Saturday towards the end of last month we took a train to Moutier in the west of Switzerland, half an hour from the French border, to attend an opera in a shooting range. We had tickets to hear my friend Annina Haug sing the role of Fenena in Giuseppe Verdi’s Nabucco at Stand’été, an annual festival of the arts held in the local stand de tir, now decommissioned, a pleasantly eerie, Charles-Addams-like structure on a hill above the municipality. We were also keen to visit the little town itself, which had recently voted to secede from the canton of Bern and join the neighboring canton of Jura as an exclave.

The opening day of the Stand’été’s 2025 edition fell on June 21, the date of this year’s Summer Solstice—the longest day of the year, and a clement midsummer—; but the festival organizers, not taking any chances, had erected marquee tents over the picnic tables set up in the forecourt of the performance venue. And when it suddenly began to hail out of a clear blue sky as we munched fish and frites before the opera began, I was inclined to respect the locals’ perspicacity. We finished our dinner and hurried inside, to take our seats for a marvelous production by the Compagnie Opéra Obliqua, under the direction of Facundo Agudin.

Verdi’s first great success, Nabucco is based on a combination of Biblical accounts. The libretto, by Temistocle Solera, pits Jerusalem against Babylon, Jehovah against Baal, Hebrew against Assyrian. The plot is convoluted: King Nabucco (short for Nabucodonosor, the Italian form of the name of the historical Nebuchadnezzar) is besieging the Jewish capital, where the Hebrews are holding his daughter Fenena hostage. When Nabucco enters the city and its inhabitants attempt to use their pawn to keep him at bay, the princess is instead released by the traitorous Ismaele, a Hebrew soldier with whom she has been having an affair.

It transpires, however, that Abigaille, another, albeit secretly illegitimate, daughter of Nabucco’s, is also in love with Ismaele, and in a fit of jealousy and driven by murderous ambition, she schemes to have her sister killed, her father removed, and herself made queen in his stead. When Nabucco learns of the plot against him and re-asserts his kingship, declaring that he is also a god, he is struck down by lightning in retribution, and goes mad. Taking advantage of his debilitated state, Abigaille has herself crowned and prepares the execution of the captive Hebrews along with Fenena, who has converted to Judaism to save her lover. Abigaille’s treachery is foiled by the return of Nabucco, who has had his sanity restored through his own conversion to Judaism. Nabucco exalts Jehovah and topples the statue of Baal, and the opera ends with Abigaille’s suicide, and the wedding of Fenena and Ismaele.

Nabucco is a fixture in the repertoires of opera houses around the world. It is undoubtedly best known for “Va, pensiero” (Fly, thought), the hymn sung by its chorus of Hebrew captives in Act 3 that came to be associated with the Italian independence movement of the 19th century. As with Biblically themed spirituals intoned by enslaved Africans in the American south, the Chosen People lamenting in exile by the banks of a foreign river lends itself easily as an allegory for a present-day political situation: in the case of the Risorgimento in the 1840s and beyond, Italian patriots keen to throw off the Austrian yoke.

HEBREWS

in chains, at forced labour by the banks of the Euphrates

Fly, thought, on wings of gold;

go settle upon the slopes and the hills,

where, soft and mild, the sweet airs

of our native land smell fragrant!

Greet the banks of the Jordan

and Zion’s toppled towers.

Oh, my country so lovely and lost!

Oh, remembrance so dear and so fraught with despair!

Golden harp of the prophetic seers,

why dost thou hang mute upon the willow?

Rekindle our bosom’s memories,

and speak of times gone by!

Mindful of the fate of Jerusalem,

either give forth an air of sad lamentation,

or else let the Lord imbue us

with fortitude to bear our sufferings!

The opera’s setting has since proved susceptible to other contemporary projections by proponents of Regietheater, or director’s theater, who have re-imagined the Hebrews as refugees at sea or (inevitably) as concentration camp inmates.

At Stand’été in Moutier this past June, artistic directors Rubén Amoretti and Robert Bouvier chose a generic, early-modern-peasant look for the chorus, an anachronistic clash with the antique Orientalist costumes of their Babylonian attackers. But it didn’t much matter how the opera was staged, because in June 2025 its contemporary correlatives were quite literally in the air.

Just one week earlier, on June 14, Donald Trump had staged a wildly expensive parade, ostensibly to mark the 250th anniversary of the founding of the United States Armed Forces but in fact a transparent move to celebrate his own 79th birthday and dictatorial apotheosis. On the same day, millions had also protested his government with “No Kings” marches across the United States; Trump was embarrassed by the curtailment of his elaborately planned display, by its sloppy execution and the poor attendance numbers, and, following these reversals, by the revolt against his signature legislation by his chief ally, Elon Musk. Meanwhile, just the day before, the Israeli military, while continuing to make war against civilians in Gaza, had commenced its bombardment of Iranian nuclear facilities. The US would join the Israeli campaign on June 22, having been equivocal about its involvement during the intervening week but repeatedly signaling its inevitable collaboration: driven in part, perhaps, by Trump’s desire to distract the public from the humiliation he had suffered on June 14.

So it was hard not to receive Nabucco, that night in Moutier, as a straightforward commentary on the current geopolitical situation: a savage idolater (Trump/Nabucco) declares himself supreme being and is punished for his hubris; he is deserted by a faithful follower (Musk/Abigaille), who attempts to remove him and take his place; he then seeks redemption by joining an ancient monotheistic force (Israel/Israel) in visiting destruction on the very idol (theocratic Iran/Baal) he has himself worshipped. His succession is furthermore secured: the turncoat bastard is removed, and the tyrant’s genuine scions (MAGA/Fenena and the Hebrews) follow him on the new path of righteousness, in the train of a punishing and vengeful figure (Netanyahu/Jehovah).

The Biblical past of Nabucco, onto which the 19th-century Italian patriots had cast their dreams of a future in liberty, now seems to be projecting its own vision of the future onto our present day. When the Hebrew captives sing their famous “Va, pensiero” chorus in Act 3—a version of the psalm “By the rivers of Babylon” sung by mourners for a lost homeland who are resigned to a life of exile and a proto-Zionist anthem—they are reproved for their defeatism by Zaccaria, their high priest, who conjures for them a bracing vision of the coming destruction to be wrought upon their enemies.

ZACCARIA

coming upon the scene

Oh, who is it that weeps? Who is it raises lamentations,

as of timorous women, to the Everlasting?

Oh, rise up, brothers in anguish,

the Lord speaks from my lips.In the obscurity of the future I see…

Behold, the shameful chains are broken!

The wrath of the Lion of Judah

already falls upon the treacherous sand!HEBREWS

Oh, happy future!ZACCARIA

To settle upon the skulls, upon the bones,

hither come the hyenas and the snakes;

midst the dust raised by the wind

a doomed silence shall reign!

The owl alone will spread abroad

its sad lament when evening falls …

Not a stone will be left to tell the stranger

where once proud Babylon stood!HEBREWS

Oh, what a fire burns in the old man!

The Lord speaks through his lips!

Yes, the shameful fetters shall be broken,

the courage of Judah is rousing already!

Here is a savagely optimistic prediction of the future that might have served to inspire the oppressed in a later age: between the World Wars in Europe, for instance, as Jews and others considered possible responses to the growing fascist threat: organized resistance or flight from bondage? In such a climate it would have been imperative to imagine various futures, whether utopian or dystopian, and to act accordingly, at the potential cost of such action wreaking further destruction.

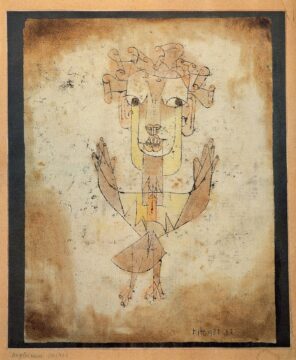

Unlike Paul Klee’s “Angelus novus”, however, as read during that dire period by Walter Benjamin in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940), Zaccaria sees catastrophe not in the past (or indeed present), but still to come. Benjamin intuited a wind blowing Klee’s angel backwards into the future as it gazes in horror at the past; the wind, which we in the present are inclined to take for progress, mounts ruin upon ruin as it rushes us ceaselessly onward in our fallen state—forward into an ever greater descent. In Zaccaria’s version of the future as presented in Nabucco, the wind blows not from Paradise but in Babylon, the source not of innocent delight but of evil depravity; and the future the prophet discerns in the darkness is our own present day, in which self-proclaimed theocratic kings make constant war in the name of peace.

In a recent re-interpretation of Benjamin’s ecphrasis, the Swiss cultural theorist Sandro Zanetti draws our attention to the eyes of Klee’s angel, which are turned very slightly to the right of the painting’s viewers. Can it be, Zanetti wonders, that the angel is aghast not so much at the ruins of the past, but at our own inability—for we are still, after all, to be counted among those viewers—to see the danger in our own present, the threat approaching us from the right?

Klee’s painting, which has been on view as part of an exhibition in Berlin, returns this week to its permanent home: at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. To the country that had once seemed a sanctuary to those threatened by fascism—for all that it had been settled, as in Zaccaria’s vision, “upon the skulls, upon the bones”—but whose political class has now thoroughly thrown in its lot with a resurgence of that same threat, on a geopolitical scale.

For my part, when we emerged from the performance that evening in Moutier, I was grateful to live in a country in which shooting ranges are refurbished as opera houses; where territorial disputes are settled at the ballot box rather than on the battlefield; and where a sudden violent irruption from the heavens proves not the madness of a savage tyrant, but the civic prudence of hail insurance.