by Priya Malhotra

Virtue wasn’t always gentle.

In ancient Rome, virtus was a word of force and visibility. It came from the Latin word vir, meaning “man,” and encompassed ideals of military bravery, civic leadership, and public excellence. A virtuous man was someone who acted decisively in the public sphere—whether in war, politics, or the courts. Virtus was not about goodness in the moral sense. It was about fulfilling one’s public role with courage and competence. The term belonged to action, and it was earned through what one did, not what one avoided.

But like many powerful words, virtus changed as it traveled. As Latin gave way to the languages of medieval Europe, and Christianity replaced classical philosophy as the dominant moral framework, the term began to morph. Virtus became vertu, and then “virtue.” Its meaning narrowed, softened, and interiorized. Instead of valor, it came to suggest moral purity, humility, and patience. Instead of a call to public greatness, it became a standard of private behavior—especially for women.

By the late Middle Ages, “virtue” in women had become nearly synonymous with chastity. It was a euphemism for sexual propriety, and a woman’s moral worth was often judged not by her integrity or courage, but by whether she had preserved her virginity, and later, her marital fidelity. Her virtue was not something she earned through action, but something she was expected to carry—like a fragile inheritance, one that could be irreparably lost. The woman who guarded her virtue was good; the one who “lost” it, no matter the context, was fallen.

The consequences of this shift weren’t merely symbolic. They shaped how women were viewed, valued, and remembered. A woman’s virtue could determine her marriage prospects, her reputation, and her legal status. It was both an irrevocable statement of her morality and a form of social capital. And over time, traits such as restraint, silence, and obedience became associated with female virtue.

This didn’t mean women completely lacked agency or complexity. They made difficult moral decisions constantly—often in conditions of constraint. But there was scant moral language to describe and give credit to those decisions or actions. Only when a woman’s strength came in the form of patience or sacrifice, was it sanctified. However, when it came in the form of autonomy or ambition, it was seen as far from praiseworthy.

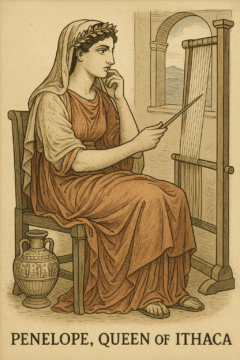

You can see this dynamic clearly in the story of Penelope, queen of Ithaca in Homer’s Odyssey. She is, on the surface, one of the most honored women in the classical canon—a figure of loyalty, cleverness, and endurance. For twenty years, she maintains her household in the absence of her husband Odysseus, who disappears after the Trojan War. As suitors descend on her home, and demand her hand in marriage, Penelope devises a plan: she promises to choose a husband after finishing a burial shroud, then secretly unravels it each night to delay the decision.

Her ruse is brilliant. Her patience, extraordinary. Her solitude, heavy with uncertainty. For two decades, she sustains order amid chaos, resists exploitation, and preserves not just her own integrity but the stability of her household and kingdom. Her actions are active, deliberate, and brave.

And yet, Penelope is remembered first and foremost for her fidelity. Her virtue, as the story has been culturally transmitted, lies not in her political skill or psychological endurance, but in her chastity. She becomes a symbol of female goodness because she waits. Because she does not stray. Because she abstains.

This is not an accident of interpretation. It’s a reflection of how virtue, as applied to women, has long favored absence over presence, withholding over assertion. Penelope’s actual choices—her quiet authority, her emotional discipline, her tactical brilliance—are overshadowed by the simple fact that she did not betray her husband. The breadth of her character is flattened into a single moral note.

Her story is a case study in the narrowing of virtue’s meaning. It shows how easily the substance of a woman’s strength can be reframed as passivity, how complexity can be collapsed into simplistic symbolism. Her courage becomes loyalty and her strategy becomes modesty.

Meanwhile, at nearly the same historical moment that women’s virtue was being distilled into restraint, the word was being reanimated in another direction—through men, and through politics.

In Renaissance Florence, Niccolò Machiavelli reintroduced the concept of virtù in his political writings. But Machiavelli’s virtù had nothing to do with chastity or humility. It meant force of character, cunning, the ability to shape events to one’s will. His ideal ruler did not need to be good; he needed to be effective. Virtù was about results. It was about boldness in the face of uncertainty, strength under pressure, a kind of strategic fearlessness. In other words, the word regained its Roman sense—ambition, action, and mastery of the public sphere.

This revival stood in stark contrast to how virtue functioned in relation to women. While male virtue was being unmoored from conventional morality and expanded to include power and adaptability, female virtue remained tethered to sexual morality and personal modesty. One gender’s virtue was a license to act. The other gender’s was a mandate to refrain.

By the 19th century, this divergence had hardened into doctrine. In much of the Western world, a woman’s virtue was treated as both sacred and precarious. Once compromised, it could not be fully restored. The idea of the “fallen woman” became a moral category unto itself—unredeemable in literature, in religion, in social life. A man could stray and still be considered virtuous, if he repented. A woman who strayed was simply undone.

And yet, despite this constriction, women have always quietly stretched the meaning of the word. Through literature, protest, and everyday survival, they expanded the space of what could count as virtuous behavior. In the 19th century, characters like Jane Eyre insisted on moral integrity even when it meant walking away from love. In the early 20th, suffragists reclaimed virtue as civic duty—marching, organizing, and demanding a place in public moral discourse. They wore white not to conform to the Victorian ideal of chastity, but to strategically subvert it. They understood the power of symbols—and how to wield them against the status quo.

Today, the word “virtue” is still alive—still evolving, still contested. In some circles, it retains its old purity-focused connotations. In others, it is deployed ironically or critically, as in the phrase “virtue signalling,” a term that mocks public displays of moral commitment. But across cultures and communities, women continue to redefine what the word can contain. It can now mean integrity under pressure, the strength to say no, or the courage to walk away. It can live in ambition, in accountability, or in dissent.

What began as virtus—a masculine honor earned on the battlefield—was narrowed into a feminine silence preserved in the home. But words, like women, refuse to stay where they’re told. Virtue is no longer merely what is withheld. It is what is upheld. Not by those who passively inherit the word, but by those bold enough to reclaim it—and redefine it on their own terms.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.