Jonathan Lethem at The Current:

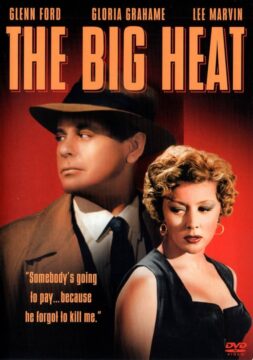

It starts with a gun, a hand, a staircase, a clock. A woman descends the stairs at the sound of a shot. A policeman, we are soon to learn, has committed suicide, but the behavior of his fresh-minted widow is coolly utilitarian. She conceals his suicide note, and telephones criminals, rather than police; her call results in further calls, by criminals, to further criminals. The telephone in The Big Heat (1953) will be more than a conveyor of bad news, though it is always that. The opening sequence of calls announces an instant metonym for a power network of dubious alliances stringing a city and civilization together. The mode is one that would have been familiar by 1953: the collective expressive atmosphere that would come to be called “noir”—one that this film’s director, Fritz Lang, had famously helped to invent. We are secure in the company of a master of cinematic evidence-gathering: the exacting hand and the pitiless eye of Lang—the most accomplished, imperious, and notorious of the contingent of German émigré directors in 1930s Hollywood.

It starts with a gun, a hand, a staircase, a clock. A woman descends the stairs at the sound of a shot. A policeman, we are soon to learn, has committed suicide, but the behavior of his fresh-minted widow is coolly utilitarian. She conceals his suicide note, and telephones criminals, rather than police; her call results in further calls, by criminals, to further criminals. The telephone in The Big Heat (1953) will be more than a conveyor of bad news, though it is always that. The opening sequence of calls announces an instant metonym for a power network of dubious alliances stringing a city and civilization together. The mode is one that would have been familiar by 1953: the collective expressive atmosphere that would come to be called “noir”—one that this film’s director, Fritz Lang, had famously helped to invent. We are secure in the company of a master of cinematic evidence-gathering: the exacting hand and the pitiless eye of Lang—the most accomplished, imperious, and notorious of the contingent of German émigré directors in 1930s Hollywood.

Lang fled the Nazis in 1933, arriving first in Paris, where (like Vladimir Nabokov) he created one French-language work before crossing the Atlantic to make a life’s creative home in exile. His recruitment to the American studio system was news: Germany’s most prominent director arrived trailing fame, his stylized science-fiction epic Metropolis (1927) among the most legendary of silent films, his M (1931) enshrined as a modernist masterwork of the early sound era.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.