by Steve Szilagyi

How would you act as a great ship slipped beneath the waves? Freeze? Panic? Leap into the sea? If you were a man, would you quietly help women and children into the lifeboats? We all wonder. Elbert Hubbard wondered too. In 1912, less than a month after the Titanic vanished into the Atlantic, he sat at his desk and wrote The Titanic, a vivid imagining of the ship’s final moments. He studied the behavior of the wealthiest passengers, John Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim, George Dunton Widener—and found it good.

“There was not a single case of flinching—not one coward among the lot. The millionaires showed themselves worthy of their wealth,” Hubbard exulted. He reserved special admiration for Isadore Strauss, heir to the Macy’s fortune, and his wife, Ida. When offered a place in a lifeboat, Ida refused to leave her husband. “All these years we have traveled together,” she said. “And shall we part now? No, our fate is one.” The two were last seen walking into their stateroom, arm in arm, to meet death side by side.

Most of us will never face that test. But Elbert Hubbard did. Three years later, he and his wife Alice were first-class passengers on the Lusitania’s final crossing. And when German torpedoes tore through the liner’s hull, Hubbard found himself living the very scenario he had once so confidently narrated. How would he face it? Did he flinch?

Before departing, a friend warned him of the danger. Hubbard waved him off. “I have no fear of going down with the ship,” he boasted. “I would never jump and scramble for a lifeboat.”

Brave words—but Hubbard was above all, a man of words. By then, he had moved perhaps a hundred million copies of a pamphlet called A Message to Garcia, delivered countless lectures, and built a public persona as an oracle of success. Admirers called him an inspiration; critics called him a huckster. He was hard to categorize, slippery to define.

To understand how he ended up on the deck of a sinking ship, we need to return to where his journey began.

Young and wealthy. In 1872, Hubbard was a poor boy on a hardscrabble Illinois farm. Desperate to escape, he became a traveling soap salesman. A pioneer of innovative sales tactics like direct-mail marketing, he sold tons of soap. The company promoted him to a top executive position. Soon, Hubbard found himself quite wealthy, quite young, with a wife and growing family.

In 1892, twenty-three years before the Lusitania sailed, he abandoned business with the intention of doing something more meaningful. Already a skilled copywriter, he announced to friends and family that henceforth, he would seek art and glory through literature. Traveling to Cambridge, Massachusetts, he presented himself at Harvard, expecting the college to welcome him as an older student with valuable life experience. The Harvard professoriate sniffed and slammed the door in his face—a public humiliation he never forgot.

Still stinging from Harvard’s rebuff, Hubbard sought inspiration in England. In Hammersmith, London, he came upon the workshop of author and designer William Morris and his Pre-Raphaelite circle. For Hubbard, it was a life-changing moment.

The Kelmscott Press, housed in Morris’s workshop, was a temple of craftsmanship. Every book it produced was a deliberate rebuke to modern industrial shoddiness: handmade paper, hand-cut type, intricate woodcut illustrations, and bindings that echoed the richness of medieval manuscripts. The entire enterprise was steeped in Morris’s reverence for medieval design, where beauty, labor, and utility were fused into objects of uncompromising excellence.

A commune of craftspeople. Hubbard returned home determined to create an American version of Morris’s Kelmscott combine. In 1895, he set up the Roycroft Press in East Aurora, New York, near Buffalo. Under his direction, it grew into a kind of commune of craftspeople, designers, and illustrators dedicated to bringing Arts and Crafts ideals to America. He built a medieval-style compound of workshops and dormitories, and a tower office where he could retreat to think and write. For many of the idealistic young people who flocked there, Roycroft was a merry place—full of good fellowship, farm work, horseback riding, and sports. Though tinged with socialist ideals, Roycroft was a profit-seeking enterprise, owned and operated by Hubbard, who used his super-salesman powers to promote both its products and himself. To accommodate the many VIPs and curiosity seekers who wanted to see Roycroft firsthand, Hubbard built on-site lodging, the Roycroft Inn (today a 3.5-star hotel).

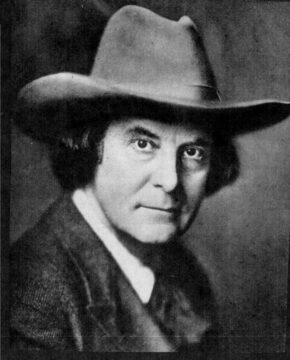

In his salesman days, Hubbard had been something of a mustachioed dandy. Now that he was artistic, he adopted a new look: collar-length hair, blousy shirts, and flowing bow ties—an Oscar-Wildish look that could get a man knocked down in the street. But topped with a good old Stetson, he remained a regular guy who liked baseball and horses. New acquaintances expecting pretension found him patient, polite, and a good listener with a mild demeanor.

That same year, Hubbard launched The Philistine, a monthly periodical that became his most potent tool of self-promotion. Each issue featured his breezy takes on life, the arts, and current events. Pages were broken up by spot drawings from the likes of W.W. Denslow, illustrator of Frank L. Baum’s first Oz book, and punchy aphorisms and epigrams—which flowed from Hubbard’s pen by the thousands. (Hubbard shrugged off frequent accusations of plagiarism, replying with the Whitmanesque, “I contain multitudes.”)

A religious skeptic. The Philistine became a must-read for free-thinkers, artists, and broad-minded bourgeois. Hubbard made no secret of his religious doubts and had the good fortune to be condemned from conservative pulpits. But he was hardly a revolutionary. On the lecture circuit—even in vaudeville—he was what we might now call a motivational speaker. He preached self-improvement, self-reliance, thrift, and good habits.

Professional cynics like H. L. Mencken sneered: “A man of immense business capacities,” whose ideas were “a mélange of platitudes… A new and characteristically American type of humbug, half Barnum and half Chautauqua.” But while he might have been half hokum, no one could could go wrong following his precepts for success or reading the books he recommended. He wasn’t selling anything but his own cheery opinions, and the Arts & Crafts knockoffs from his Roycroft workshops.

For all his sweetness and light, Hubbard was still boss over a team of salaried minions. One day in 1899, possibly irritated by a bumbling employee, Hubbard dashed off a short essay—shorter than the one you’re reading now—called A Message to Garcia, which went on to become one of the most widely read and reprinted pieces of writing in human history.

Garcia told the true story of an American soldier, Rowan, ordered to deliver a message to a Cuban officer during the Spanish-American War. Rowan faced hazards but asked no questions and got the job done. Hubbard’s point was simple: obedience and perseverance are the virtues most lacking in American business.

Teaching obedience. After publishing Garcia in The Philistine, Hubbard printed a few hundred pamphlets to circulate and promote Roycroft. Then he seemed to forget about it. But one pamphlet came into the hands of a top railroad executive, who thought: “Doggone it, this is the sort of thing our employees need to read to make them more obedient.” He ordered reprints. Soon, every business in America seemed to want copies. Ultimately, anywhere from 10 to 100 million copies (depending on whom you ask) were distributed. Hubbard, Roycroft, and Garcia became household names.

The real message of Garcia, though, was financial. Hubbard learned that businessmen were hungry for articles that confirmed their biases, and they were willing to pay big money for reprints. It was here, a critic from the left would say, that Hubbard began openly currying favor with the rich. He began both subtly and blatantly seeding The Philistine with tributes to the titans of industry, hoping they would order thousands of copies as corporate giveaways—and often, they did.

Hubbard wasn’t interested in building a larger personal fortune. He was all about Roycroft. The enterprise ran on thin margins, and if praising the virtues of the wealthy now and then fattened the operating budget, he was willing to add their sensibilities to the multitudes he contained.

Titanic, sincerity and buncombe. When the unsinkable Titanic went down in 1912, Hubbard was among the first into print with a vivid dramatization of the event and its moral lessons. With the mixture of sincerity and buncombe that characterized all his works, Hubbard made it a tribute to the character, virtue, and stoicism of the first-class passengers. He helped focus the narrative on the gallant men who observed the code of “women and children first,” to the exclusion of the disaster’s broader human scope.

Hubbard’s The Titanic made some people spitting mad. One socialist newspaper raged: “The millionaires Astor, Guggenheim, Straus—martyrs and saints… And what of the steerage immigrants, huddled like cattle below decks, whose names were never printed at all? Where are their monuments? This is how the capitalist press teaches us to weep.” The Masses sneered: “Hubbard never met a rich man he could not turn into a parable of moral virtue.”

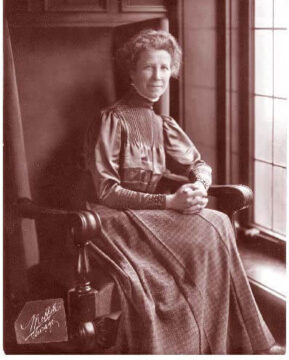

Hubbard did not respond to this, or to other criticism that came his way—though he got plenty of it in his life. Even in the matter of adultery. When, in 1903, it became public that he was maintaining both a wife and four children in Buffalo, and a mistress with a love child in East Aurora, scandal erupted. He was shunned by Buffalo society, and even some Roycroft followers departed in protest. But Hubbard never publicly acknowledged wrongdoing or expressed regret. Instead, he quickly divorced his wife, married his lover—the outspoken feminist Alice Moore—and continued on as before.

The coming of war. The Titanic article got attention, but it was not a hit on the scale of Garcia. The world moved on to other topics, and Roycroft hummed along nicely, printing books, making furniture, and hammering copper candlesticks. Then came the Great War.

At first, The Philistine mocked the European conflict. But as horrors mounted, Hubbard’s beliefs shifted. “Big business is to blame for this thing,” he wrote. He accused industrialists of “selling murder machines to the mob”. In particular, he blamed Kaiser Wilhelm for “lifting the lid off hell.” Thousands of pro-German Americans canceled their Philistine subscriptions in protest. Hubbard hitched up his pants, and told his associates that was tired of hearing about the war secondhand – he was going to go to Europe to see it for himself.

Hubbard was only 58 years old. A celebrated man who’d achieved his life’s dreams. Why did he hazard a trip to Europe? In the weeks leading up to the departure, he seemed to hint that he had a message for the Kaiser, and that if he could get a 0ne-on-one with the German leader, he could persuade him to make peace. But the most likely reason was that Hubbard considered himself an important man, the war was an important event, therefore, he ought to be there to check it out. In a letter written shortly after his departure, he jokingly referred to himself as “ex-officio General Inspector of the Universe with the power to investigate anything.”

One more rejection. But there was a hitch. In 1913, Hubbard had been convicted under the Comstock Law for sending “obscene” material through the mail (the material being a remark alluding to birth control in The Philistine). His conviction cost him his passport. If Hubbard were someone else, he might have taken this as a “sign”, stayed home and lived on into old age. But the passport rejection may have revived his old hurt at being turned away by Harvard. Hubbard would not be denied. He applied directly to President Wilson himself, who swiftly granted him the needed papers.

So, around noon on May 1, 1915, Elbert Hubbard and his wife mounted the gangplank to board the RMS Lusitania. Hubbard had been warned that the trip might be hazardous. “I’ll meet the Kaiser in hell,” he joked in reply. Once the ship was underway, Elbert and Alice Hubbard were seen by many, walking arm-in-arm about the deck. With his long hair and western hat, he was a recognizable celebrity. The two no doubt dined at the captain’s table and took part in shipboard fun.

Terrific panic. All was well until 2:10 p.m. on May 7, when the first torpedo struck amidships. A second followed soon after. The captain of the submarine that had fired the torpedoes gazed through the periscope at what he’d wrought. As he wrote in his log:

The ship was sinking was unbelievable rapidity. There was a terrific panic on her deck. Overcrowded lifeboats, fairly torn from their positions, dropped into the water. Desperate people ran helplessly up and down the decks. Men and women jumped into the water and tried to swim to empty, overturned lifeboats. It was the most terrible sight I have ever seen.

After the explosions, Hubbard and Alice emerged from their inner cabin. According to one witness, “Neither appeared perturbed in the least”. The couple stood on the boat deck, gazing over the chaos of smoke, confusion, and swinging lifeboats, seemingly weighing their options.

Hubbard had his arm around his wife’s waist. Alice couldn’t swim.

An acquaintance rushing past saw that they had no lifebelts. “Wait here,” he said, “I’ll get you some.” When he returned, the Hubbards were gone.

Inside the ship, a steward spotted them in a corridor. They were walking arm in arm. Hubbard was calm. “We will go to our stateroom,” he said, “and await the end.”

When the steward looked back, he saw them enter the cabin, and shut the door. Their bodies were never recovered.

(Hubbard’s writings can best be sampled in the collections Elbert Hubbard’s Scrap Book and The Note Book of Elbert Hubbard, published by Roycroft. Both books have been among my favorite bedtime reading since childhood. They are entertaining and inspiring. Author Freeman Champney’s 1968 Art & Glory is a thoughtful and readable account of Hubbard’s life—I lean on it a great deal here. I took the submariner’s account of the Lusitania sinking from Dead Wake, Erik Larson’s definitive 2015 book on the disaster. The Roycroft Campus and Roycroft Inn still are still going concerns in the beautiful town of East Aurora, New York, an easy drive from Buffalo, Chautauqua, and Niagara Falls. They are well worth a visit.)

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.