by Tim Sommers

The first time I tried to take a shower in Italy, I stubbed my toe, tripped, and smacked my face into the shower wall. In fact, I did that pretty much every time I took a shower there. Turns out it is not that uncommon there to have a 4-inch barrier that you have to step over to get into the shower.

I also hit my head frequently while there. I had a leg cramp from trying to bend it far enough to sit in the tiny seat of an otherwise capacious boat. Somebody said to me, “Your height is a real disability here.”

I thought, “Is it? Could it be?” I’ve been told all my life that being tall is a good thing and I’m not that tall (6’4’’). What makes something a disability? Is just any kind of inability a disability? Could it be less a matter of who you are and more about the environment – and/or how you are treated by others? It turns out that one of the most important disputes in Disability Studies concerns whether disability must be a “bad” difference – or a “mere” difference. Let’s look for that fault line by trying to define disability.

One definition of disability is any departure from normal functioning. But that can’t be right. Perfect pitch, exceptional athletic ability, or mathematical genius are departures from normal functioning.

How about disability as a negative departure from normal functioning?

There are negative departures from normal functioning that we don’t call disabilities; genetic susceptibility to a disease, being very tall, being abnormally bad at basketball or math. But there’s a bigger problem with this definition.

Being obese is largely considered a negative, and it can have negative health effects (although how big a problem it is all by itself had been disputed), but there is evidence to suggest that obese people are more likely to survive certain kinds of heart disease and cancer. (It’s called the “obesity paradox” and it is, I admit, controversial.) Deaf people often don’t regard deafness as a negative and where they have access to education and work they appear to be happier overall than nondeaf people. In fact, many people labeled disabled report not being worse off than others not so labeled.

Maybe, then, disability is just the lack of an ability that most people have. But most people, though not all, can roll their tongue, tell right from left, and/or ride a bike.

So, how about a lack of significant ability that most people have? Not all disabilities are based on abilities., i.e., HIV, epilepsy, and major depressive disorders are counted as disabilities by the Americans with Disabilities Act, but they are not about a lack of a specific ability.

Can we instead define disability in terms of well-being? A disability might be anything that makes life worse for you. Clearly, however, there are many things that make life worse for us, like fast food, cable news, and eating too much salt. These are not disabilities. Also, as in the examples above, it’s not the case that people with disabilities are always either less happy overall or specifically unhappy about their disability.

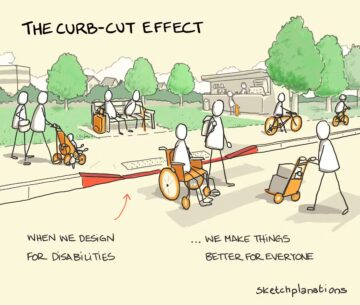

How about this? Disability is the negative effect of discrimination, or lack of accommodation, by the society that you live in. This is a social definition of disability. It moves past the idea that there is one universal, negative, and immutable understanding of disability; because the actual impact of differences between people are always mediated by people’s attitudes, the availability of health care, and the mismatch between the built-environment and the person. (Trivial, I know, but it’s hard for me to cook, for long periods, because kitchen counters are too short for me and hurt my back.)

Some disability advocates argue that, in fact, a person has a disability, if and only if, they identify themselves as having a disability. This goes too far for me. It’s metaphysically dubious since with most things what you think or say is true about it is not the determinative factor in what is true about it. Also, people can have issues that present problems or even dangers for others, whether or not they acknowledge they do. And people can identify as being disabled when the evidence suggests that they are not – or have suspect motives for so identifying.

Nonetheless, the idea that disability is partly socially created is what people mean when they say disability, like race, is socially constructed. I found it hard initially to wrap my head around the possibility that disability is a social construct. On the other hand, it’s always seemed obvious to me that race is. So, I find it clarifying to think about the social construction of race for comparison.

Racial categories change over time. For example, Irish and Italian people were not considered white when they first came to the U.S. – and the question of whether or not people of Hispanic descent are white is controversial and politically important. Different societies also categorize race differently. Someone considered “Black” in the U.S. might not be categorized the same way in Jamaica, Brazil, or South Africa.

There’s no gene for being black or white or asian. Genetic variation within so-called racial groups is often greater than between them. Racial categories were created or solidified to justify unequal treatment (e.g., slavery, colonization, segregation). “Blackness” in particular was created to justify (and, in a way, contain the Atlantic slave trade).

I am not disputing that people are related to and tend to look like their parents, siblings, and grandparents – or even that groups of people living in separated geographic regions differ in the distribution of certain traits from the distribution of those traits among some other groups from elsewhere. The dispute is over whether sorting people into races has any natural, asocial or presocial validity. It doesn’t. Ask a biologist. And, furthermore, people are not nearly as good at sorting people by race as they think they are, hence, the idea that race is obvious upon inspection is spurious..

Similarly, when it comes to disability, no one is denying there are important mental and physical differences between people, only that there is no neutral, wholly descriptive, “scientific” way to sort people into the objectively disabled and objectively nondisabled. Instead, people are a cluster of many different traits and abilities that interact in various ways. How they react to them, how society reacts to them, and whether the built world accommodates everyone is part of what makes something a disability.

Even isolating some particular ability and then attempting to demarcate an exact point at which a certain lack of ability becomes a disability may be impossible. Instead, disability, again, is relative not just to person’s abilities, but to people’s attitudes and the environment they find themselves in.

The Americans with Disabilities Act says “An individual with a disability is defined as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment.”

I am not here to dispute that definition. I am sure the people who formulated it know more about it than I do. And it’s formulated for a very good purpose – to fight discrimination against people with disabilities. I just want to point out one clause, i.e., a person who has a disability is “a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment.”

Here I think the definition acknowledges, without necessarily fully endorsing, the idea that disability is a social construct. Again, being a social construct doesn’t mean that there are not a variety of important differences between people – some of which are, or are perceived to be, less than ideal. Nor does it deny that for some purposes we have to define disability as best we can (see, ADA). But social construction is not a liberal trick. Peter Berger, one of the cofounders of social constructivism (see, The Social Construction of Reality) was not only a sociologist, but also a political and social conservative and a Protestant theologian. The point of social construction is to say that, especially with evaluative terms, the reality that we see is partly shaped by social forces that don’t necessarily reflect some uncontroversial and immutable reality. To be sure impairment is real, but disability, and this is the point, is defined by our response to disability – attitudinally, but also in terms of the public physical environment we construct.

For my part, I would go so far as to say that the point of focusing on social construction is that some things that your society tells you have to be a certain way actually don’t have to be that way. Social construction, at least a plausible version thereof, doesn’t deny objective reality. Social construction says a lot of what we think of as “objective reality” is in fact the internalized norms of our particular culture. For disability, this suggests that some of what we see as disability is better understood as a mix of an individual’s abilities and inabilities, whether their built-environment is constructed in a way that includes them, and what people’s attitudes are about these kinds of differences.

“The natural distribution [of traits and abilities] is neither just nor unjust;” John Rawls wrote. “These are simply natural facts. What is just and unjust is the way that institutions deal with these facts.”