by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

“You can’t fall that far in Japan.”

Writer and photographer Craig Mod arrived in Tokyo when he was only nineteen. In many ways, he was already running. Running from a challenging childhood, running from bullies. And running from that feeling like he was always just one step away from disaster because of violence and lack of opportunity in his hometown.

It’s a story we know: of people leading middle class lives in a factory town—maybe in the mid-west? —only to watch when the factory closes and the whole town becomes suddenly out of work. This leads to hardship and poverty, which can, and often does, lead to drugs and violence. And in Mod’s case, it led to trauma when his best friend, who’s like a brother to him, is murdered— another casualty of economic injustice.

But even before Bryan dies, Mod already knew he wanted to get as far away as possible from the place where he was born. He longed to see the world and maybe be able to grow as an artist and as a human being. But in a world of constant struggle, that is easier said than done.

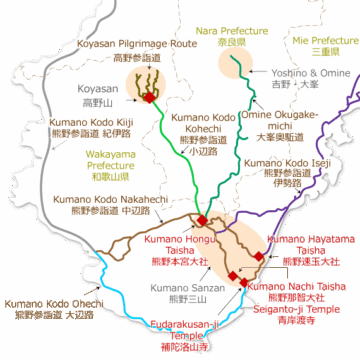

Almost on a whim, he lands in Japan, where he begins to take long walks. Crisscrossing the country on ancient pilgrimage routes, like the Kumano Kodō, Mod starts opening up to people. And he is astonished by this new land in which he’s found himself, where so many of the problems back home had simply been solved.

Not to say it’s perfect and definitely not to say that Japanese people don’t have their own problems, but as he explains, in Japan, the safety net is stronger. And so, even the least fortunate citizen cannot fall that far. Part of it is simply having universal healthcare, outstanding public transportation, and a solid public education infrastructure—one that is not based on wealth and zip codes like back home. That alone makes life less fraught, he says, and work becomes less perilous since your job no longer determines life and death healthcare outcomes nor the quality of your children’s education.

And so, arriving in Japan was a revelation. And feeling less vulnerable, he slowly begins to open himself to the world.

2.

2.

I was a few years older than Mod when I first arrived in Tokyo, having just turned twenty-two, but I had a similar experience of healing. My comparatively affluent hometown in California couldn’t have been more different from Mod’s —and yet in retrospect, I was also struggling mightily when I washed up in Japan. It was shortly after the death of my father after a brutal battle with cancer which coincided with my graduation from UC Berkeley and my time as a student coming to an end. Up till then I had been a student my entire life.

Because these things coincided, there wasn’t enough time to mourn my father, but there also wasn’t time to attend job fairs or make elaborate career plans—I had to get any job fast, had to keep moving. But like Mod, I was running—basically trying to outrun a deep sadness and anxiety. Maybe if my father’s death had happened when I still had a year to go in college, maybe then I would have had time to process things, but in my case, there wasn’t that luxury—and coming from a non-religious and small family, there were no rituals to help give my grief some voice. I traveled around India and Indonesia first, but it was in Japan where I began to heal.

Like Mod, I immediately felt myself part of a community in which people were looking out for me, quickly meeting my future husband and new friends. Even in a big city, somehow my neighbors welcomed and looked out for me. This intensified when I married and had a child, when I felt myself cared for in a way I never managed to achieve in my home country outside family and a very few close friends in California. And I have to say as a woman, though I did not come from a town with any challenges like Mod experienced, still I was afraid of men and violence. But in Japan, my fears slowly subsided. Walking alone at night, I never felt I had to be defensive. And you know the old story of losing your wallet only to be given it back later when someone hands it in to the nearest police box—money all present and accounted for. That happened to me too!

Mod captures this feeling so beautifully in his book when he describes how long it took before he lost the anxiety he felt when out walking and a car pulled alongside him—because back home that could mean violence or robbery, whereas in Japan the person was inevitably curious about him, and would offer to give him a ride. In America, he felt himself abandoned by the whole, whereas in communitarian Japan, he discovered that people look out for each other— not always, but in general, the longer you live there the more you find yourself embedded in a community of care.

3.

3.

Returning back to California at forty-three years old, I found life in America to be even more dog-eat-dog than I remembered. America has never been a collective or communitarian society, but greed and struggle seem more ubiquitous than I recalled. I am not only talking about the communities ravaged by zombie drugs and joblessness like Mod experienced, but rather even in affluent places the high-stakes competitive nature that we are forcing on our kids is pretty sad to see –you might call it a kind of meritocratic ideology if it wasn’t for the elite gaming the system so unfairly.

Again and again, I have wondered, how we can cultivate our moral or artistic lives in an environment of struggle and scarcity?

Scarcity is in important word in Mod’s book. By scarcity he is not just talking about financial scarcity but rather is referring to a state of affairs where people are in many ways pitted against each other in the rat race, something that is hard to opt out of if you have kids who need to be educated and have health care.

And Mod brings up an interesting point, one that has haunted me since returning to America. How can human flourishing exist in a place of scarcity, when character cultivation and compassion requires the time and space to notice and listen to the world around us?

4.

4.

My fellow Japanese translators sometimes talk of being puzzled by all the books being published these days highlighting Japanese concepts, like forest bathing, or ikigai, or kintsugi etc…

I tend to buy and devour these books since often, in the microcosm of a word or concept, you can find embedded an entire worldview. It is so interesting to see the way words don’t always map across languages and cultures, which is why translation is so inherently interesting.

Mod does something interesting with a particular word to capture the space that opened up in his heart in Japan and personal self-growth. And this word is called yoyū.

Yoyū is an everyday very common expression in Japanese meaning “having extra.” The word suggests being able to do something with ease. It is having time and space—having a margin. I would say it also points to an ability to be satisfied with less, or just to be more easily satisfied with what is, instead of the self-clinging grasping that so often dominates life back in the U.S. At least that is how it feels to me.

Back home, everything, Mod says, was tainted by this scarcity mentality. But in Japan, what he finds is the opposite: an abundance of heart; enough to be respectful and mindful of others, to have the time and mental space to stop and appreciate the full moon or the scattering blossoms and fallen leaves. Or to trust someone who pulls up alongside you in a car to offer you a lift.

He writes:

There’s a word in Japanese that sums up this feeling better than anything in English: yoyū. A word that somehow means: the excess provided when surrounded by a generous abundance. It can be applied to hearts, wallets, Sunday afternoons, and more. When did this happen to me? This extra space, this yoyū, this abundance. Space that carried with it patience and—gasp—maybe even… love?

5.

5.

His book, Things Become Other Things, which everyone in the world should read—seriously! beautifully demonstrates what a society that is organized in a different way can enable; for example prioritizing the collective good and flattening economic disparity. After all, it takes a certain yoyū to be able to care for other people. Because if you constantly feel you’re under attack or that you’re barely surviving, or worse if you are terrified your kids might fall between the gaps in the gig economy, there’s no space, nothing extra to care for others. But if the baseline starts higher like in Japan, where there is a humane safety net, there is space for compassion for others.

I know I am preaching to the choir since most readers here already know this is true. But so many times, I found myself in tears reading this memoir—maybe because Mod’s journey was so deeply touching. Like Mod, I only planned to stay a year in Japan, but also like Mod would not leave for over twenty. And not a day passes where I don’t miss my life there like a pain in my chest.

Reading his wonderful travel memoir, imagining his long walks crisscrossing the country on ancient pilgrimage routes, I felt myself falling in love with Japan all over again. My time there rewired my brain, making me less selfish and more giving, which is something he also talks about in his book. It gave me the ability to listen rather than talk about what I wanted or needed all the time. In America, I think it is true that we are taught to value and stick up for ourselves from an early age. And yet Mod says he felt abandoned by the whole and found it hard to love and value himself. Reading this beautiful memoir, following along step by step as he crisscrosses the mountains and narrow paths that cling to the sea, I realized how much this story was a pilgrimage within. And how much I love Japan.

++

For More:

- Mod’s book is out in paperback. You can also splurge on the exquisite special edition.

- Having a society where people can be satisfied with less is also beautifully expressed in the film Perfect Days, where the protagonist is also living in a very tiny six mat Japanese apartment. If you are interested in things Japanese please consider subscribing to my Substack Dreaming in Japanese

- My Lithub essay about another contemplative book, this time about the novel Stone Yard Devotional, by Charlotte Wood.