by Martin Butler

In the 1980s being non-judgmental was very much in vogue. The idea was that you should withhold from morally judging other people and their actions, at least in a significant number of cases. It was an imperative that I came across in all sorts of contexts. I, however, thought it very misguided. Why should we be non-judgemental? It seemed like an abdication of our moral commitments, a kind of moral cowardice. And in any case, I thought it almost impossible not to judge other people and their actions. Of course we might choose not to voice those judgements, and perhaps this is what those promoting the non-judgmental attitude really meant. At the time I thought non-judgmentalism resulted from a half-baked moral subjectivism, the idea that there is no objective right or wrong and so I shouldn’t expect the actions of others to meet my own subjective moral standards – to do so would be an illegitimate imposition of my morality onto others.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

A moral theory that at least appears to justify a limited form of non-judgmentalism is the moral philosophy of liberalism as presented by John Stuart Mill. This is encapsulated in the harm principle: we should be allowed to act as we want provided we don’t harm others. But of course this doesn’t stop us judging the actions of others, it merely requires that we don’t interfere or attempt to curb those actions simply because we disapprove of them, with the proviso that others are not harmed. Although it is notoriously difficult to establish a clear definition of ‘harm’, the virtue of this approach is that it allows for a distinction between what we might regard as morally wrong and what the state should outlaw. Judging something offensive, for example, cannot be regarded as sufficient grounds for it to be outlawed. It does not however get to the nub of what non-judgmentalism is about.

There are other important theories which might be used to justify non-judgmentalism. Determinism is a potential candidate. If we view the actions of others as the inevitable result of causal factors beyond their control, the very notion of blame (and praise) and thus moral judgment become incoherent. It is to endorse what is sometimes described as ‘cosmic blamelessness’. To judge an action negatively usually means believing that the action should not have been chosen by the agent. But to believe an individual should not have acted as they did is to believe they could have acted otherwise. Ought implies can, as Kant neatly put it. Without the ‘can’ the ‘ought’ becomes meaningless. The trouble with this approach is that the moral judgment of the action by others can also be regarded as an inevitable part of the causal nexus. Both the agent and the judger become blameless. So we end up where we began. In any case, to deny human responsibility is to deny humanity itself. That is true however we understand determinism. So non-judgmentalism, if it is to have any coherence, is certainly not about claiming that human beings have no responsibility for their actions. That would be to reduce them to objects and their actions to mere events. To treat someone as fully human is to understand them as free agents with the power of choice.

I have now changed my mind about non-judgmentalism. The era of the internet seems to have produced a torrent of rampant judgmentalism from all sides, so the idea of holding back on judgement, a little at least, seems far more appealing. I now see non-judgmentalism as an important element in any fully thought-out humanitarianism. Far from being evidence of moral cowardice or moral subjectivism, it is quite the opposite. This does not mean of course we abdicate all moral judgement but it does mean that we recognise our own fallibility and the fallibility of others. A strident moralism is in many ways the easy option. To endorse an uncompromising Manicheism in which the world is sharply divided into good and evil is a psychologically safe and satisfying position to hold. To show moral uncertainty can of course be regarded as moral weakness, moral ignorance or worse, which is why it is easier to make clear cut moral pronouncements on every occasion. But if we crank up our moral judgements to 11 on every issue we lose any discrimination. The judgements that really do matter get lost in a sea of overreaction, the moral equivalent of crying wolf.

Non-judgmentalism is about developing the virtue of humility which means recognising that ambiguity, nuance and uncertainty are all too real, and so holding back on judgment can often be the more truthful response. At the very least it means recognising that there are many cases – more than we might think – where easy moral verdicts need to be complex, conditional and nuanced, and should not be immediately pronounced.

Despite the decline in religious belief, it often seems that we are hanging on to the worst aspects of religion. Religious belief was often thought of as giving morality an absolute foundation, but secularism, far from producing a drift into a mushy moral relativism, seems to be moving us towards an unforgiving moral self-righteousness, the kind that was all too evident in periods of religious persecution. We see this on all sides of political and moral debate.

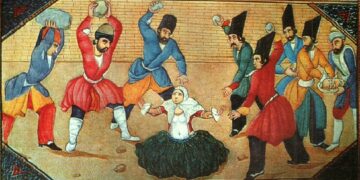

This is not just about judging action, it is also about judging the moral worth of people. An example of this in recent years has been evident in the rise of identity politics which, apart from being philosophically incoherent, has lead to a tribalism in which those on the wrong side of the fence are ‘othered’, the modern version of being beyond the pale. One way in which we can counter this tendency in ourselves is to keep own moral fallibility in mind: “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.” This is not simply because we risk being hypocritical, it’s more than this. It’s to recognise that moral judgement is not an abstract act like completing a mathematical equation. It’s something we do as agents embedded in the world of real and messy human relations, and this context should allow us to recognise the pressures and human flaws from which we all suffer. We can’t assume the moral purism of a disembodied moral calculator. I think a certain degree of pity is in order when we survey the human condition. Here I can begin to see the value of the notion of original sin. It can, or at least should have, an equalising effect, and can be the basis for a more forgiving humanitarianism. And I am not denying here that the idea of original sin can also be behind some appalling immoralism.

Good drama, literature and film can be an important means whereby we are reminded that the world is, by and large, not composed of heroes and villains but of the inadequate, the insecure and the struggling who are capable of both good and bad, sometimes at the same time. (Breaking Bad is a good example of this in recent years.) Unfortunately there has also been a tendency for characters to become mouth pieces for generalised identities or easily understood caricatures.

Being non-judgmental is not the same as being morally disengaged or morally nihilistic, quite the contrary. To recognise where clear moral judgment is needed, and where there is uncertainty and ambiguity, requires full moral engagement and a belief in the importance of such judgment. It demands that we step beyond the broad general principles that appear to give moral clarity and involve ourselves in the particularities and messiness of actual moral decisions. It is at this level that complications and uncertainty emerge, but it is here, also, that moral certainty becomes forcefully evident.