by Mindy Clegg

Since the 2024 election, liberals, progressives, and the left has been wringing our collective hands over why Trump won yet again. Was it the racism, the misogyny, or the economy stupid? Was there some fraud happening behind the scenes? Was the Democratic party “too woke” or not “woke enough”? Did the Democrats ignore the common clay of the new west in favor of “they/them”? Did they lose the propaganda war? Was it people not voting or was it people voting, but against them? Do we blame white men, white women, Black men, Latinx voters or those who did not vote at all? Endlessly, on and on. Partisans of each explanation insist that they have the only real answer to the question of why Trump. But I would say that rather than singling out one reason as the answer, there are grains of truth in each.

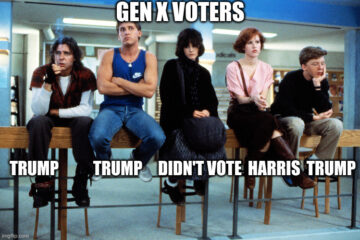

Yes, people are struggling, even as the economy has been doing well. Yes, people did not vote for the obviously more qualified Black/South Asian woman because of misogyny and racism. Yes, the democratic party can be out of touch. Yes and more. History tells us that rarely is a single answer satisfactory in explaining events like this. But another I have not really seen is what role does nihilism play in the recent election. We know that trust in our shared institutions are at an all-time low across political divisions. While the roots of that are in the failures of those institutions, culture—especially culture lacking in political specificity but that positions itself as outside the mainstream—drove a commodified version of rebellion against our institutions. You can especially see this with the rise of “alternative” culture in the 1980s and 1990s. As such, Generation X took away a specifically nihilistic message that often provided no strong political sentiment. Many white Gen Xers seemed to have carried that worldview into the politics today, preferring a bomb thrower to political problem solver. That bomb thrower was seen as being more authentic, despite his obvious history of lying.

Can a desire for greater authenticity, motivated by an idealistic worldview, curdle into a nihilistic worldview that shapes? We can all look at the world and see the very real flaws of capitalist modernity, after all and want better for us and ours. We can think about, discuss, debate, and demand something better, more in line with society’s stated values and with our own sense of the real and just. We can even make choices as citizens to demand better. These demands drove youthful countercultural arguments from the 1950s to today. However, often these demands were channeled into consumer culture rather than into political processes. From the beats to punks, the second half of the twentieth century saw attempts to drive political change via rebellious countercultural art. Consciousnesses might have been raised, but how effective were they in creating political change? Sometimes, yes, changes have been made for the better, and people got politically involved thanks to the music that they consumed.

But political advocacy via art did not always translate into political action. The above documentary shows a group of politically engaged young people, but the dark side is there as well. The racist skinheads they sometimes fought were also Gen X. Youth culture could drive a sense of anti-establishment nihilism, too. We saw that in the history of punk rock. If punks sometimes became more political aware and active, in some cases, people embraced more problematic messages from the music that they made an important part of their lives. Many white Gen Xers into punk culture embraced the anti-establishment messages of rejecting institutions, paving the way for some to embrace a bomb thrower like Donald Trump. The ironic, eye-rolling pose of the early 1990s alternative culture that was influenced by punk foregrounded the nihilism of rejection rather than being actively engaged in political transformation. For some nihilism was the primary message of punk, becoming the heart of their understanding of “authenticity.” They got the message of “reject everything” rather than “work to transform what is unjust.” The outcome of the recent election should indicate to us that an embrace of “outsider” culture does not necessarily mean a progressive mindset. Trump, despite coming from wealth and privilege, ran as an outsider and that was convincing to some voters, especially white men. People take away what they want out of culture, especially that which reinforces their world view. As Gen X came to reject institutions that no longer seemed to be working for them, some sought to destroy those institutions by voting for the person who promised to destroy them. They took inspiration from the culture they grew up with, which told them that institutions will let you down. They’ve seen the truth of that with their own eyes, though. But that’s because one political party has been working to dismantle those institutions and make them far less responsive to the needs of the public. And around we go.

This was a cultural process that developed over the course of several decades. As historian Grace Elizabeth Hale noted in her book A Nation of Outsiders, the concept of rebellion became a key cultural aspect of the postwar period. White middle class people came to identify themselves with cultural outsiderness, while having an entire society built for them. In the 1950s, the beats articulated a strong anti-establishment centered on a strong rejection of white, suburban consumerism. Works like Kerouac’s On the Road or Allen Ginsberg’s Howl set the tone for cultural criticism of the kind of consumerism promoted in the immediate postwar years. Baby boomers, the primary beneficiaries of that era’s consumer economy, embraced the cultural offerings that were aimed at their cohort. It made life more enjoyable, after all. But many young people who ended up in college (again, white, middle class suburban kids primarily) found it harder to square their sense of optimism of the early 1960s with their political views as the long 1960s wore on. If early rock was aimed at enjoying life and teenged love, rock became more political charged during the 1960s. Hippies embraced that culture and advocated for dropping out of mainstream society and living in alternative ways. If some counterculturally inclined boomers regularly criticized American institutions, they were far less likely to go after the culture industries, which promoted anti-war talking points. Yet these industries also benefited from American foreign policy which led to an expansion of American culture abroad during the Cold War. The recording industry and Hollywood produced pleasurable commodities that seemingly reflected the political views of their audience. Rock stars and famous actors articulated the same concerns of many in the counterculture. It became an effective strategy for channeling the concerns of youthful self-identified rebels. Despite the rebellious message that railed against corrupt institutions that were feeding a massive war machine, it was more about focusing on the individual and rebelling by dropping out instead of greater involvement aimed at progressive change.

Many Generation X also embraced rebellion via consumption and individualism. Gen X was a smaller generation that saw the beginnings of the dismantling of the liberal consensus or the New Deal order. The New Deal transformed society, but by the 1970s, there was evidence intransigence and corruption of those in power. This reality was weaponized and racialized by the right, winning power during the Reagan revolution. The powerful New Deal administrative state became something that the voting public could hold to account for real and perceived institutional failures. By 1980, many white baby boomers embraced the Reagan revolution which had a strong critique of institutionalism and claimed the anti-establishment position. This period saw the rise of hardcore underground punk scenes. These second wave of punk scenes (sometimes described as postpunk) went underground in part because a wave of punk panic. Starting with the ill-fated tour of the Sex Pistols, the media started to imagine punk as a fundamentally violent, anti-parent subculture leading teenagers astray. Commercially oriented independents demanded that their signees shed their punk identity and embrace a more corporate friendly “new wave” image. Bands refusing to do so ended up having to forge their own paths to share their music with an audience outside of their local communities. The result was a globally situated translocal punk scene that operated on the margins or outside of the mainstream music industry prior to the widespread adoption of the internet.

But of course it was a minority of Gen Xers that embraced the punk underground. So-called “alternative” music would have a much larger reach. By the 1990s, punk was having a renaissance in the mainstream and punk-influenced “alternative” music was going mainstream. Some punk bands had hits on MTV, while the major labels began signing bands from hardcore scenes such as Green Day, a band out of the Bay area scene. This “pop-punk” wave followed on the success of Nirvana and other grunge bands. Both had the energy and sound of punk rock, but they were often less specifically political. Not all underground punk bands were political, but many expressed a left-leaning anti-establishment worldview that they often shared with their audiences. As bands formerly of the underground gained larger audiences, they sometimes shed politically charged messaging while holding onto an anti-establishment image. Compare a band like Reagan Youth to Bad Religion. Reagan Youth explicitly invoked Nazi Youth in the name of their band. It’s a specific political position vis-a-vis their view of the Reagan administration and Reagan’s policies. They stayed largely underground. Bad Religion gained mainstream success. Their songs railed against various American institutions, such as Christianity in their song “American Jesus.” While calling out those invoking faith to justify war, one could certainly flatten the role of faith in American life, which has served both liberatory and authoritarian causes. While the messaging of Reagan Youth can be seen as much more politically explicit, there exists some ambiguity in the later works of Bad Religion.

The lack of specificity meant that people could ignore the political and embrace the “vibe” of the music instead. Sometimes people just ignored political messaging of post-punk bands that won mainstream success altogether. Take the example of Rage Against the Machine, one of the most obviously left-wing bands to emerge into the mainstream during the alternative era. Some people seemed to miss that reality. Enter conservative politician Paul Ryan, a one-time member of congress and vice-presidential candidate. He claimed to love Rage Against the Machine, which elicited a response from none other than guitarist Tom Morello himself in the pages of Rolling Stone. Morello noted that Ryan is part of the machine that his band was raging against. Over the next few years, websites that cover music news continued to publish stories about right-wing Rage fans shocked (SHOCKED!) to learn their favorite band was “woke.” It should surprise no one that when you bring rebellious underground culture into the mainstream the politics can be blunted, even if the political content does not change. Popular music, contrary to popular opinion, has almost always had strong political messaging. But the commodification of music itself often shaves off that political edge. The often harsh, aggressive music influenced by hardcore (and gangsta rap and heavy metal) delivered a nihilistic message, whatever other political messaging might have been intended.

Generation X were raised in the midst of the dismantling of New Deal and as adults have lived through the consequences of that. The cost of raising a child has risen, and there are far less resources for the elderly, so many Gen Xers are feeling this “sandwich” squeeze of caring for both their children and their parents. But Gen X was told that we can not depend on any larger institutions to help us. Much of the popular culture we grew up with reinforced that message, that institutions merely fail us, and can’t be depended upon. These institutions that benefited their parents have completely eroded for our generation and we watched it erode. In that light, it seems understandable that some might vote for the bomb thrower over a problem solver—at least I’ll get a tax cut, the thinking goes. But I doubt finishing the destructive job started during the Reagan will solve the many problems our generation or younger cohorts face. Political nihilism rarely works for those who vote for it, only deepening the crisis of institutionalism. Perhaps it’s time to start democratically rebuilding these institution to better serve us instead of blowing them up in a snit of nihilism. We should reject the narrative of the recording industry that punk only existed to shake up the industry and is now dead. Today, punk still exists as a form of democratic community building, much more than just a nihilistic rebel yell against the past for its own sake. Members of any and all generations should work together to save our institutions and make them work better for everyone, not just the elite class currently dominating the Republican party and the leadership and primary funders of the Democratic party. We all deserve more than just divisiveness and false promises.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.