The Monty Python sketch of Thomas Hardy writing “The Return of the Native” takes place inside a packed soccer stadium with an announcer providing play-by-play analysis of the author’s glacial writing process. In hushed tones, the announcer says that Hardy has started to write, but wait, “oh no, it’s a doodle … a piece of meaningless scribble.” At last, Hardy writes “the,” but then crosses it out. In the time it takes to play an entire soccer match, he barely produces a sentence. In fact, Hardy was a speedy writer. He created “The Mayor of Casterbridge” so quickly that if he were outside, he “would scribble on large dead leaves or pieces of stone or slate that came to hand,” Paula Byrne writes in a new biography, “Hardy Women.”

The Monty Python sketch of Thomas Hardy writing “The Return of the Native” takes place inside a packed soccer stadium with an announcer providing play-by-play analysis of the author’s glacial writing process. In hushed tones, the announcer says that Hardy has started to write, but wait, “oh no, it’s a doodle … a piece of meaningless scribble.” At last, Hardy writes “the,” but then crosses it out. In the time it takes to play an entire soccer match, he barely produces a sentence. In fact, Hardy was a speedy writer. He created “The Mayor of Casterbridge” so quickly that if he were outside, he “would scribble on large dead leaves or pieces of stone or slate that came to hand,” Paula Byrne writes in a new biography, “Hardy Women.”

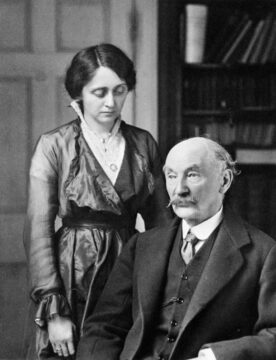

Artists at work, whether Paul McCartney hashing out the chords to “Let It Be” or Jane Austen drafting “Pride and Prejudice,” are a fascinating bunch. And yet, much as I love Hardy’s novels, I’d never imagined how (or why) he composed anything. In fact, I scarcely thought of Hardy as a person; I focused entirely on his heroines — Tess, Eustacia Vye, Sue Bridehead — the ultimate compliment for a novelist. But now, thanks to Byrne’s magnificent book, I’ve learned that Hardy (1840-1928) was as strange and compelling as the women he wrote about.

More here.