by Derek Neal

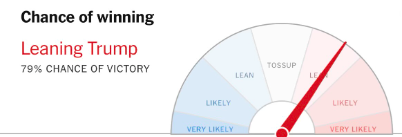

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

Over the course of my two and half hours at the bar, I ended up in conversation with three different men. M. was the man to my right. I’m normally not much of a talker, but the election provided an easy conversation starter. “Are you following the election?” I asked him. It was loud and I had to repeat my question. M. mumbled that he wasn’t but asked how it was going. “Looks like Trump might win,” I said. M. raised his eyebrows, which were flecked with grey, and said something along the lines of, “Well, he has some ideas.” I had trouble making out what M. was saying, partly because of the noise in the bar, but also because M. spoke so softly. It was as if he didn’t believe in the importance of his own words. Talking or not talking, it didn’t seem to matter to him.

I pulled out my phone again. Trump was at 82%. I showed M. Then he took out his phone, a flip phone. “I’ve still got this old thing,” he mumbled. This seemed like an opening for a new conversation—a discussion on the merits of “dumb” phones versus smartphones, on phone addiction, on attention. “Why’d you get one of those?” I asked M., gesturing at his phone. He looked away and started talking about privacy with smartphones, and how he didn’t want people tracking him, or something along those lines. “How do you like the flip phone? How long have you had it?” I asked. M. said he’d had it since 2016, and that it didn’t cause him any problems because he didn’t have a job, but it sure made meeting women difficult.

M. was tough to categorize. He didn’t have a job and he had a terrible phone, but he was also well dressed and handsome. His jeans were cuffed at the bottom and he wore a beige knit cardigan. Perhaps, I’m thinking now, he was involved in some sort of illegal activity, but he didn’t carry himself with the confidence or brashness that one might expect in that case. M. was a shy, timid man, drinking pint after pint alone at the bar. His voice faltered when he spoke and he averted his eyes. The truth is I didn’t know anything about M, except that he seemed to be a regular at this bar, talking occasionally with the bartender and being greeted by others.

A new man came in named D. He was the opposite of M., loud and talkative, immediately attracting attention to himself. He slapped M. on the back, said he hadn’t seen him in forever—how ya doin’ man? Then he came over, sat to my left, and ordered a Miller High Life. M. mentioned that I was following the election as I’m American. I pulled out my phone and told D. that Trump was going to win and currently had an 85% chance of winning according to the fateful New York Times speedometer. “Fuck that guy,” D. said. “Man, fuck him,” he repeated. D., being a talker, seemed to like to repeat things. He cursed Trump again and then began to say that this “wasn’t our election.” “This is gonna be terrible for immigrants,” D. said, “but it’s not our election.” “This is gonna be awful for LGBT people,” D. said, “but it’s not our election.” “The guy is crazy, he built a wall on the border—who builds a wall on the border!? But, hey, it’s not our election.” The refrain of “but it’s not our election” seemed to act as a sort of soothing balm, reminding him that he shouldn’t despair too much, because he lives in Canada.

D. asked me who I voted for, and I told him I voted for Kamala Harris. D. asked M. who he would have voted for, and M. said Trump. D., who had been passionately criticizing Trump, did not seem concerned that M. would have voted for Trump, perhaps because it was hypothetical, or perhaps because he knew something about M. that I didn’t. D. leaned over to me and whispered: “M’s a quiet man, dude, such a quiet man. Make sure you talk to him.” I nodded and sipped my stout. The conversation continued. I told D. that I’d lived in Montreal at one point and D. told me about his trip to Montreal. He’d visited a porn theater called “Cinema L’amour.” I’d never heard of it. “Have you ever seen Taxi Driver?” I asked him. D. said he had and that he remembered the scene where Robert De Niro takes Cybill Shepherd to a porn theater on a date. Then he turned to a woman on his left and began talking to her about something, leaving me alone with my thoughts as M. had gone out for a smoke.

I sipped my stout—it was almost done by this point—and I thought about the scene when Charles Palantine gets into Travis Bickle’s (Robert De Niro) cab. Palantine is a presidential candidate. When Bickle recognizes him, Palantine asks him what single thing he’d like the next President to do. Bickle responds:

Well, he should clean up this city here. It’s full of filth and scum. Scum and filth. It’s like an open sewer. I can hardly take it. Some days I go out and smell it then I get headaches that just stay and never go away. We need a President that would clean up this whole mess. Flush it out.

Who would Travis Bickle have voted for, I wondered. I’d read an article a few days prior, published the day before the 2016 election, which cited a study showing the single most predictive factor of support for Trump was not gender, class, or race, but a “penchant for authoritarianism.” Bickle would have supported Trump, I’m sure. But why would someone who wants to “clean up the city” take their date to a porn theater—a “dirty” place? Most interpretations of Bickle’s character explain this choice as social awkwardness, saying that he’s so inept he doesn’t understand a porn theater is not the type of place to take a respectable date. In Paul Schrader’s script, he suggests another interpretation: “But then there’s also something that Travis could not even acknowledge, much less admit: That he really wants to get this pure white girl into that dark porno theatre.” What is it that voters with a “penchant for authoritarianism” cannot acknowledge, much less admit?

I ordered another beer—a Modelo—and realized a new man had taken the place of D. to my left. This man was also a talker, but perhaps it was just the late hour—around midnight—and the fact that the bar had cleared out considerably. The new man, J., asked me what I was doing, and I told him that I was following the election and figured I might as well follow it at a bar as opposed to my apartment. My mind was still on Travis Bickle, and I admit I felt a bit like he must have in his taxi, cruising the streets late at night, listening to anything his passengers wanted to tell him. For whatever reason, people at the bar seemed to want to talk to me, and I had nothing to do but listen. The New York Times speedometer was up to 90%. J., perhaps seeking to establish common ground, mentioned that he didn’t really follow politics but was concerned about how people no longer spoke to each other across the political divide. I agreed with him. Then I asked J. what brought him into the bar. He took a deep breath, then told me the recent events of his life: he was newly separated, he had an eight-year-old son, this was his “weekend,” he’d just been to a concert, now he was at the bar, his wife was all sorts of crazy, you had to watch out for women, a lot of men in his situation would’ve let themselves go but he wasn’t doing that, he’d learned to set boundaries, he’d learned to reconstruct his life putting himself first, he was living his best life—women, man, watch out dude, you’re young, but trust me—he made good money but was almost broke with all the expenses, he was thriving, he was doing good because he had no other choice but to do good.

I liked J. In my mind I thought about how there were two sides to every story—in this case, his wife’s side—but I also recognized that he had suffered and seemed to have constructed a narrative for himself that allowed him to continue living a meaningful life. We all need stories to tell ourselves, I reasoned. I have my story. I wasn’t sure if M., who was still sitting on my right, had a story he could tell himself. Perhaps that was the appeal of Trump—one could buy into his story instead of constructing one’s own—and Harris, what was her story?

After the election, I began to hear about how young male voters had helped elect Trump. In 2020, 41% of men aged 18-29 had voted for Trump. In 2024, that number rose to 56%. In Schrader’s script for Taxi Driver, Travis Bickle is 26 years old. In one scene, we see Bickle working out as he narrates in voiceover:

I gotta get in shape now. Too much sitting has ruined my body. Too much abuse has gone on for too long. From now on I’m gonna do fifty push-ups each morning, fifty pull-ups. There will be no more pills, there will be no more bad food, no more destroyers of my body. From now on it’ll be total organization. Every muscle must be tight.

Bickle’s various attempts to organize his life fail, yet he fetishizes rule and order—if only he could get it all together, he thinks, everything would be solved, and his pain and suffering would subside. Is that what the young men who voted for Trump think? That Trump can be the authority figure they’ve been looking for, that instead of figuring out their own lives, Trump can do it for them? I’m not sure. In four years, the data may swing back the other way, and we may be telling a different story.

At the beginning of Taxi Driver, Bickle says, “All my life needed was a sense of direction, a sense of someplace to go,” while at the end he has convinced himself that, “My whole life has pointed in one direction. I see that now. There never has been any choice for me.” “I am not a fool,” Bickle says. “I will no longer fool myself. I will no longer let myself fall apart, become a joke and object of ridicule.” At the end of Taxi Driver, it seems that Bickle has finally found the direction, the guidance, the authority he’s looking for, misguided as it may be.

When I eventually got up from my stool at 1 am, The New York Times speedometer was somewhere above 90%. I said goodbye to J. and shook his hand, then shook it again. My way out was blocked by a few people, and it had been some time since I’d said a word to M., who had continued to drink pint after pint. I wanted to shake his hand, too, but I was in an awkward position, standing behind him, so I said goodbye and that it was nice to meet him, then squeezed past the people blocking my way. M. turned halfway around and mumbled something to me that I couldn’t make out. I should have shaken his hand, but I was already thinking about the following morning, when I would have to stand in front of my class as their authority figure. I couldn’t be late—I had to set a good example—but now, I thought, I also had to somehow show them that they didn’t need me.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.