by Michael Liss

We are now on opposite sides of the moral universe. —Joseph Buckingham, journalist and Massachusetts State Senator, speaking of his once esteemed friend, Daniel Webster.

What a wonderful quote. Thirty years of amicable relations destroyed in the course of a three-hour speech. March 7, 1850. Senator Daniel Webster taking his leave of old friends and older ideals as he seeks the higher ground of political peacemaking.

Webster’s story is one of eight Senators’ featured in John F. Kennedy’s 1956 Pulitzer Prize winning book Profiles In Courage. This is as good a time as any to acknowledge what everyone knows: The book is the story of political integrity, but JFK really didn’t author most of it. The bulk of the research and writing was done by his long-time speechwriter Theodore Sorensen. Let’s also acknowledge that JFK’s dad, Joseph P. Kennedy, might have “assisted” in nailing down the prestigious award.

Such is politics, and such is the process of image creation and image burnishing. Profiles In Courage was the end product of a JFK idea inspired by the actions of then-Senator John Quincy Adams, who, in 1807, opposed his Federalist Party’s foreign policy and was denied renomination as a result. Kennedy took the story to Sorensen, asked him to do further research, and Profiles is the result.

The book serves a real political purpose. The Kennedys (father and son) have their eyes on the future and don’t have a lot of time to waste. JFK was under 30 when he was elected to the House in 1946; 35 when elected Senator in 1952. He’s 39 in 1956, surely old enough to set his sights higher. JFK has a great political name, charisma to burn, and even a personal history of physical courage (PT-109), but, still, at that age, the resume is clearly incomplete. A book, especially a well-received one that shows some gravitas, might lead to a VP slot on the 1956 ticket with presumptive nominee Adlai Stevenson. A man could dream and a man could plan, and Profiles was part of the plan.

Is it worth a Pulitzer, Dad intervention or not?

Honestly, it’s not an extraordinary book. Sorensen is an excellent writer, but he’s not a historian, and, with space limitations, he’s basically writing thumbnail descriptions of complex historical events, occasionally losing accuracy or nuance. There are also complaints about the motivations behind some of Kennedy’s selections—a man on the make looking toward a future nominating process in which Southern Democrats play a significant role is perhaps a little prone to including sympathetic descriptions of Southern Democrats.

With all its flaws, why read it, especially when JFK himself probably only had a significant role in the first chapter, “Courage in Politics,” and the last, “The Meaning of Courage”? Perhaps that’s the answer. Profiles is relevant because it gives us a look at Kennedy as a sort of impresario. He and his team searched through American history to give examples of acts of political courage and self-sacrifice that are admirable and worthy of emulation. By inference, he, too, would act that way. But Profiles is more than just an extended piece of self-promotion, suggesting that glamor and substance can exist in the same person. It is also a bit of what we would presently call “inoculation” and “setting expectations.”

Amidst the celebratory accounts of famous figures like Robert Taft, John Quincy Adams, Thomas Hart Benton, Daniel Webster, and Sam Houston, and more obscure ones like George Norris, Edmund Ross, and Lucius Lamar, there’s a whisper of the mundane. Kennedy wants you to know that most of law-making is not speechifying—it’s the nuts and bolts. That takes a different kind of courage—the courage to conform, to pay one’s dues, to take a difficult vote when asked, ultimately to be a team player when your team can’t afford to play a man down.

You do these things because, without your team, you won’t make friends when you need them, won’t be able to deliver on the matters you and your constituents care about. Your “team” doesn’t necessarily have to be just your Party. It may also, of necessity, include members of the other political party. As Kennedy points out, “only through the give-and-take of compromise will any bill receive the successive approval of the Senate, the House, the President and the nation.”

When you look at that quote, you see both a man who knows his own record might include any number of “get along, go along votes” and one who prophylactically wants to frame them as necessary. “We should not be too hasty in condemning all compromise as bad morals.”

There is a balance to be struck. A Senator who ignores the wishes of his constituents or his political party too many times becomes an ex-Senator. Independence can have a price—in JFK’s dry observation, “the possibilities of giving up the interesting work, the fascinating trappings and the impressive prerogatives of Congressional office…”

Profiles In Courage is largely about those people who do risk it and pay a price, but of all the eight that Kennedy singled out for special attention and praise, none of them played for bigger stakes than Daniel Webster, with his controversial role in the Compromise of 1850.

By the late 1840s, America was back to its usual antebellum default setting of significant, destabilizing disagreements over the existence and continuation of slavery. In the past, thanks to efforts spearheaded by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, the nation had found a way, through compromise, to a period of relative peace. In 1820, Clay brokered the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri to the Union as a slave state and Maine as a free state. It also banned (except for Missouri) slavery from the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands located north of the 36º 30’ parallel. Then, in 1833, Clay, with the consent/participation of South Carolina’s Senator John C. Calhoun, worked out an agreement in which South Carolina would step back from nullification and secession, and Congress would reduce a tariff with which South Carolina disagreed.

The underlying dynamic had changed, perhaps irrevocably. The South was being challenged by economic factors, geology, and demography, and losing the battle on each front. Older plantations were suffering from poor crop yields as a result of soil depletion. The more industrialized, better-banked North was growing much more quickly than the agrarian South, both in wealth and in people. More people meant more members of the House of Representatives, and that meant more political influence. The South’s structural political guardrail, the Senate, depended on maintaining an equal number of Slave and Free States, but that calculation had been complicated by results of the Mexican American War, the peace treaty, and the annexation of Texas. Add in the British’s ceding of the Oregon Territory in 1846, and, in just a few years, we had gone from the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase to a rising empire that reached West to the Pacific and North to the Canadian border. A key provision of the Missouri Compromise—the one that banned slavery from the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands located north of the 36º 30’ parallel—now had far greater consequences than had been anticipated at the time. Even more troubling, a Pennsylvania Congressman (later Senator) named David Wilmont entered posterity by sponsoring an amendment to an appropriations bill in the House of Representatives on August 8, 1846, proposing the banning of all slavery in land gained from Mexico in the war.

If these had been the only issues, over land and political representation, perhaps they could have been worked out. It would have needed only yet another compromise and the accompanying legislation. But there were two other factors with potent emotional components that came into play, and, to a very large extent, they were linked. The rise of Abolitionism in the North was a constant irritant to the South, which waged a long (and often successful) battle to gag debate. Southerners could not abide the intense criticism of their morals, and insisted the North enforce silence. On the other side of the equation was the Fugitive Slave Act, the enforcement of which was demanded by the South, resisted in the North. Northerners were not paragons of racial tolerance, but many were disgusted at the idea of having to be bounty-hunters for their Southern brethren.

The South was tired of waiting. At the urging of John C. Calhoun and others, they began to look at secession as an obvious means of attaining their political and economic goals. They called for a convention to be held in Nashville of like-minded states to consider the proposal and come up with a unified message. Henry Clay, who had spent his entire, long political life in support of Union, knew he had to step in again. Calhoun had made demands that Clay knew were way too much for the North to stomach, but Clay also was certain that a balanced compromise, like that of 1820, was impossible. To save the Union, he needed Northern votes, and he needed them when they would largely be against Northern self-interests. He needed the third man of the “Triumvirate” of great Senators, Daniel Webster.

Webster is just a fascinating subject, a man of uncertain personal morals, who, for decades, forcefully espoused great philosophical ones. He had untouchable gifts. Not only was he a leader of his Whig Party, but also the undisputed champion orator in an era in which the spoken word had a far greater impact than it does today. Webster’s law practice led him to present oral arguments before the Supreme Court—it is said he caused the iron-willed Chief Justice John Marshall to mist over in the seminal Dartmouth College v. Woodward case. He possessed that type of talent.

Clay knew speed was essential. If asked to choose sides, even Southerners with great affections for the Union would likely go with their region. The Nashville Convention would inevitably, through reinforcement, intensify the calls for disunion. The situation needed to be resolved before it became unresolvable. Clay’s own energies were flagging as tuberculosis tore at his lungs. He needed to act. In the middle of a January 1850 snowstorm, he went to Webster’s house to ask his assistance. Clay laid out his proposed terms and asked Webster to support them. (1) California to be admitted as a free state; (2) Utah and New Mexico to be admitted without any slavery legislation—meaning both the practical end of the Wilmont Proviso and modifying of the Missouri Compromise; (3) Texas to be compensated for yielding some of its territory to New Mexico; (4) the slave trade in Washington D.C. to be abolished; and (5) the Fugitive Slave Act to be hardened, criminalized, and expanded.

It was a huge ask, and both men were acutely aware of it. Complicating things was the fact that men like Calhoun preferred secession or disunion to any other resolution. Clay would have to get the disunionists to give up that dream, and offer at least some sort of face-saving concessions for an angry North. That might be very difficult. Further complicating Clay’s mission was Webster’s own personal history. Webster was already on record, emphatically and for many years, as opposing every significant pro-slavery element of the Compromise. Webster had a well-earned reputation as a hired gun (actually, a well-compensated hired gun), but this seemed to be a bridge too far. To get Webster on board, Clay had to insist that the greater good—the survival of the Union—was of far higher value than what was being given up. Clay believed, and imparted the belief to Webster, that the compromise was the last stop before secession and immense violence.

Clay convinced Webster that radical pro-slavery secessionists in the South and radical Abolitionist secessionists in the North would inevitably lead to disunion. Webster, by all accounts, gave in by degrees, but he did give conditional support. Further confidential discussions Webster then had with friendly southern colleagues confirmed his fears. The South was in no mood for compromises, and definitely in no mood for the status quo. On March 4, 1850, a dying John C. Calhoun made his way into the Senate Chamber. Too weak to deliver his own speech, he had it read by Senator James Mason of Virginia. The body was weak, but the will was as strong as ever. Calhoun’s demands were the equivalent of unconditional Northern surrender.

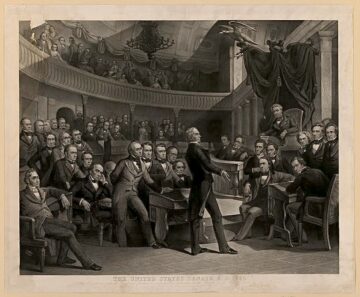

It was Webster’s moment, and he knew it. He had already concluded he would have to back Clay’s compromise. Now he prepared for it, despite numerous warnings from his constituents and influential supporters in the North. On March 7, 1850, with the galleries filled to bursting with expectant listeners, he walked into the Senate chamber and delivered what came to be known as the “March 7th Address,” an absolute barnburner.

A Daniel Webster speech was apparently more than just words—it was an almost tactile experience. His bearing, his mannerisms, his clothes, his pipe-organ of a voice, even his massive skull all produced an effect that cannot be recreated just by reading the text. The man with such a great gift for drama got one more note of it: the slightly late arrival of John C. Calhoun. Calhoun would not live to see April, but, on this day, he sits in his chair, an emaciated figure in black wrappings. Initially, Webster thinks that Calhoun has been unable to attend, but, upon learning that he is there, Webster acknowledges his presence, bows to him, openly weeps, then goes on to undermine Calhoun’s dream of disunion.

The audience listens intently and perhaps even with disbelief as Webster does a substantive about-face on virtually every position he has taken. He insists he does these things by the one virtue that supersedes all others—a patriotic love of Union. Secession is the greatest evil—it will lead to a bloody end of nationhood. To avoid secession, one must acknowledge the arguments of the other side and make concessions, even those that are painful. Union demands those concessions, and the man who had inspired so many 20 years before with his ringing “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!” would give those concessions.

Webster has put his stake down.

We have a great, popular, constitutional government, guarded by law and by judicature, and defended by the affections of the whole people. No monarchical throne presses these States together, no iron chain of military power encircles them; they live and stand under a government popular in its form, representative in its character, founded upon principles of equality, and so constructed, we hope, as to last forever.

The reaction to Webster’s speech both in the Chamber and in the country is part astonishment, part anger, part praise or rueful admiration. Its conciliatory words toward the South slowed down the movement toward secession. From some in the North came angry condemnation in highly personal terms—the dozen or so noted in Profiles are just a small percentage of the total. Yet, many in the country, particularly but not exclusively moderates and business interests are willing to try it. At this fraught moment, a great many citizens, North and South, preferred an imperfect peace to a morally pure war. They waited and, after considerable legislative drama, the essence of Clay’s Compromise ultimately passed.

Did Webster make the right decision? Union had won, if winning was defined as sustaining it. How about Webster himself? There is no question he offended many beyond reconciliation, and the extended speaking tours he went on afterwards to defend his actions did not change many minds. The man who ached for the Presidency, who opened the March 7th Address with “I wish to speak today not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American,” forgot the cardinal rule of American politics—you have to get the nomination first, and, in 1852, the Whig Convention denied it to him. He died just a few months later.

How about for America? Did Webster do something for his country? That’s a more complex question. Kennedy, utterly the politician, thought enough of Webster’s decision to include it in Profiles In Courage, and enough of Webster to absolve him of personal motives in making it. Even if you ascribe to Webster mixed motives, including the ugly one of fishing for Southern (Presidential) votes, you can certainly make the argument that the Compromise of 1850 deferred the Civil War for a decade. If you are particularly cynical (or realistic), you can note that those 10 years were a continuation of the 10 years that preceded it—not just in intensified rancor, but in continued Northern growth in population and economic potential. In 1850, the North might not have had the will or the resources to win a Civil War. In 1860, at enormous cost, it did.

Somehow that seems unsatisfactory. Kennedy says one thing that sticks:

The true democracy, living and growing and inspiring, puts its faith in the people—faith that the people will not simply elect men who will represent their views ably and faithfully, but also elect men who will exercise their conscientious judgment—faith that the people will not condemn those whose devotion to principle leads them to unpopular courses, but will reward courage, respect honor and ultimately recognize right.

Is that us? Are we ready to select leaders with conscientious judgment and have enough faith in them and ourselves to watch principles prevail? Do we even have those types of candidates?

Perhaps the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves. As JFK noted nearly 70 years ago,

A nation which has forgotten the quality of courage which, in the past, has been brought to public life is not as likely to insist upon or reward that quality in its chosen leaders today—and in fact we have forgotten.

Let us try to remember.