by Eric Feigenbaum

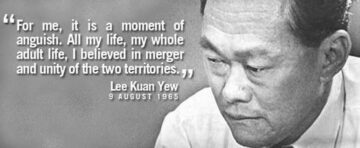

Singaporeans call it “The Moment of Anguish” – when their founding prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew broke down in tears announcing the independence of Singapore. There are relatively few surviving recordings of the actual event – a non-televised press conference on August 9, 1965 with international correspondents – but the still images of Singapore’s Founding Father with tears in his eyes, dabbing himself with a handkerchief is a key moment in the small island nation’s self-narrative.

Unlike most countries, Singapore’s independence was not greeted with celebration. It was not the result of a long-time struggle – at least not directly. At the time, Singaporeans – including Lee himself – saw independence as a failure and a moment of existential crisis.

You see, Singapore had navigated its anti-colonial struggle with Britain along with British Malaya, which in turn became the Malaysian Federation. Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak joined the federation – envisioning a single nation of related peoples. Only fractures emerged that caused the Malaysian Federation to cast out Singapore shortly before full Malaysian independence.

The issue: ethnic equality. Put simply, Singapore wanted all people to have the same rights, whereas Malaysia put the rights of ethnic Malays first – giving them extra privileges and status.

Before going further, it helps to understand what Malaysian and Singaporean even mean – and to do that it helps to rewind.

For at least 800 years, Singapore had been intermittently populated by different ethnic groups within its region and then lightly used by the Portuguese 1500’s. After 1613 when the Portuguese destroyed Malay settlements on Singapore, it was left essentially unpopulated for more than 200 years before Sir Stamford Raffles identified the island at the tip of the Malay Peninsula as his ideal for a British trading port and naval base – which came to full fruition in 1867 when Britian officially took Singapore by treaty.

The British essentially started with a tabla rasa and much like they did with Bombay, took the “if you build it, they will come” approach to a port. And it worked. Groups of Malays came down from Johor and other part of the Malay Peninsula while untold Chinese – particularly from Fujian Province – escaping famines, poverty and political instability showed up looking for work and opportunity. Meanwhile, the British needed people they could rely on and brought groups of Indians from Tamil Nadu to take on both skilled and unskilled labor with a special emphasis on civil service roles.

These three ethnic groups with no common history, culture, language or belief system ended up populating an island together. Meanwhile, In the Straits Settlement cum British Malaya just above it, Chinese and Tami immigrants began arriving to traditionally Malay populated and ruled areas.

It was this inverted population composition that created the rub. Singapore had – and still has – a predominately ethnic Chinese population with roughly equal numbers of Malay and Tamils minorities, while the rest of the Malaysian Federation was predominately Malay with a few enclaves of strong Chinese minority particularly in places like Penang and Kuching – and an even smaller Tamil presence.

To the dominant United Malays National Organization (UMNO) party that has governed Malaysia from its inception, Malaysia was a country for Malays, with minorities allowed to coexist, particularly in regions they had traditionally dominated – again, like the Chinese in Penang. Naturally, to Chinese dominated Singapore, putting Malays first sounded like a bad deal. So it was that during the two years Singapore walked the path from British colony to independence as part of the Malaysian Federation, Singapore’s leaders clashed regularly with Malaysian leadership until Singapore was finally expelled from the Federation.

At a 1965 press conference, Lee Kuan Yew said of the newly independent Singapore:

I make this promise: this is not a Chinese country. Singapore is not a Chinese country nor a Malay country nor an Indian country. That is why we said before that a Malaysian Malaysia is not a Malay country; that was why I was not satisfied. This is not a Chinese country. And after this, in the Chinese language I am going to say this is not a Chinese country. And my friends are not people who have come from China – they are the sons of the soil. … I cannot be responsible for Malaysian citizenship now. But regarding Singapore citizenship, I made this promise: you will be of equal status with me. And I promise you your special position.

Of course, as any American knows, the idea of equality is one thing and making it a universal reality is quite another. Singapore’s founders had enough examples of multi-ethnic, heterogenous countries in the world to observe and take lessons from their successes and failures.

And those founders had little time to lose once Singapore separated from Malaysia. So much needed to be done to become a functioning independent country with a robust enough economy for survival, let alone success. Seeing one another as Singaporeans, rather than a collection of peoples was essential for cooperation and collaboration. But how does one turn a lump of coal into a diamond in a heartbeat?

Singapore set out to engineer integration – to facilitate if not force a sense that people once seen as “other” were really just variations of Singaporeans. Like so many Singaporean solutions, it involved a multi-prong approach.

- Government built Housing Development Board condo blocks could have no more than 70 percent of any one ethnicity. People were forced to shift into neighborhoods that weren’t traditionally their own ethnicity.

- The government helped finance the development of places of worship – so long as those places were in neighborhoods that weren’t traditionally associated with their religions. In other words, the government would fund a mosque in a historically Chinese neighborhood and a Taoist temple in a traditionally Indian one. The idea was to force people to cross into each other’s territories and understand that in essence, people aren’t so different from one another.

- English became the medium of instruction in public schools so that no ethnicity’s language dominated over the others – but “mother tongue” classes were required by all. Eventually, Singapore loosened the rules so students could study a “mother tongue” that wasn’t their own such as a Chinese ethnic learning Malay or a Tamil Indian ethnic learning Mandarin.

- No one is exempt from national military service – all young men irrespective of ethnicity and background must serve. Everyone risks their lives for their country.

These methods began a slow, but steady process of change – especially when mixed with frequent speeches and government messaging about integration.

At the same time, Singapore draws a distinction between equal rights and functional equality. The Constitution of Singapore starts with the premise that a majority has a social and political advantage and that in Singapore’s case, Chinese ethnics are the inherently advantaged population. It actually builds a form of affirmative action into the Singaporean system.

152.—(1) It shall be the responsibility of the Government constantly to care for the interests of the racial and religious minorities in Singapore.

(2) The Government shall exercise its functions in such manner as to recognise the special position of the Malays, who are the indigenous people of Singapore, and accordingly it shall be the responsibility of the Government to protect, safeguard, support, foster and promote their political, educational, religious, economic, social and cultural interests and the Malay language.

As one of the framers of the Constitution, Lee Kuan Yew explained to Parliament in a 2009 speech:

We explicitly state in our Constitution a duty on behalf of the Government not to treat everybody as equal.

It is not reality, it is not practical, it will lead to grave and irreparable damage if we work on that principle. So this was an aspiration.

As Malays have progressed and a number have joined the middle class with university degrees and professional qualifications, we have asked Mendaki to agree not to have their special rights of free education at university but to take what they were entitled to; put those fees to help more disadvantaged Malays.

So, we are trying to reach a position where there is a level playing field for everybody which is going to take decades, if not centuries, and we may never get there.

Singapore takes a stance many Americans would find a paradox – enshrining equal rights under the law because in one sense, we are all equal – and enshrining obligations of care for segments of the population with less privilege and political power. Perhaps another way to discuss in more modern parlance is Singapore recognizes the need for both equality and equity. Being treated as equal citizens under the law is equality and making sure everyone has the opportunity for success voices that are heard despite minority status is taking an interest in equity.

For what is often labeled a conservative country, Singapore’s attempt to balance equality and equity is exceedingly progressive in the current American political spectrum.

This is a difficult view for many Americans to adopt. In a land whose Declaration of Independence declares “all men are created equal” but whose constitution stated slaves were to be counted for census as three-fifths of a person – we have yet to reconcile our various and conflicting views on what equality means, whether it exists and how it is achieved.

Even more complicating is the term equity is often co-opted by the American political left – making it somewhat taboo in more center and right political circles, even if were it presented another way those same people might appreciate the concept. After all, we don’t label people inferior or lacking for having poor eyesight – we consider it a parental, medical and social responsibility to get them corrective lenses so all can read, learn and work as productive members of society.

Perhaps we can all consider Mr. Lee’s words on the subject:

The way that Singapore has made progress is by a realistic step-by-step forward approach.

It may take us centuries before we get to a similar position as the Americans. They go to wars – the blacks and the whites.

In the First World War, they did not carry arms, they carried the ammo, they were not given the honor to fight.

In the Second World War, they went back, they were ex-GIs – those who could make it to university were given the GI grants – but they went back to their black ghettos (in 1945) and they stayed there. And today there are still black ghettos.

These are realities. The American Constitution does not say that it will treat blacks differently but our Constitution spells out the duty of the Government to treat Malays and other minorities with extra care.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.