by Rafaël Newman

Around ten years ago—before the physical and cognitive decline that began during the pandemic; before his removal from autonomy to a care home in the north end of Montreal; before his death there at the beginning of this month—my father entrusted me with his personal collection of jokes.

As he approached his eighties, the decade of their lives in which both of his parents had died, dad had begun to feel increasingly elegiac, a mode not easily compatible with his professional role as a raconteur. Indeed, by his own account, his narrative powers generally—upon which he had relied, during his career as a novelist, poet, and professor of creative writing—were on the wane. “I feel like I no longer have a story to tell,” he said during a visit I made to his apartment in 2013: and thus, a fortiori, he must also no longer be a teller of jokes.

The Word file my father mailed me, ten years ago, from his PC in Montreal’s Mile End to my MacBook in Zurich’s sixth district, is some 250 pages long and counts almost 122,000 words. It comprises between 700 and 900 jokes—it’s difficult to give a precise tally, since some of the entries are of shaggy-dog length, while others are multipart variations on a theme: spoof ad campaigns for Viagra, mock letters to Dear Abby, ostensibly alien words that turn out simply to be the phonetic rendering of “redneck” pronunciations. There are cameos by all the types familiar from the commedia dell’arte of Golden Age American stand-up: St. Peter; various “blondes” and Mothers Superior; talking parrots; bartenders; “Irishmen”; and, of course, The Lord Almighty Himself, in His aspect as begrudging distributor of attributes to tardy recipients.

What is notably absent from my dad’s jokes, however, is anything that might properly be termed a dad joke. This may be because “dad jokes” typically arise ad hoc, out of a particular real-world context, and are thus less suitable for isolated transcription and transmission than more generic, self-enclosed, typologically defined anecdotes. Or perhaps it is due to the fact that, according to my own observations, the typical dad joke is not sexist, not racist, not violent—and therefore not conventionally funny, since humor derives its explosive force, in psychoanalytic interpretation, from its ability to release otherwise shameful aggression in a socially acceptable fashion. Dad jokes also often feature—indeed, are often centrally built around—puns, which are likelier to elicit groans than laughter; and my dad, for all his professional attention to the concrete effects and semantic vagaries of language, typically grew impatient at what seemed a fetishistic dwelling on the phonemic or even lexical surface of words. What interested him, when telling a joke, was getting a laugh.

My father had evidently compiled his collection over a considerable period, because, among an extremely heterodox assortment of recent gags and witticisms copy-pasted from the internet, I discovered one of the very first jokes I recall him telling:

On the Titanic, a magician is performing for some of the passengers as the ship sails towards the iceberg. “Watch closely,” says the magician. “I’ve never done this before and I’m not sure I can do it again. On the count of three I’m going to make everything disappear. One, two—” Just then the ship hits the iceberg and all aboard are thrown into the sea. Hours later, one of the survivors, clinging to a piece of flotsam, sees the magician in the distance. With enormous effort he makes his way over to him, and when he is within earshot he shouts, with the last of his strength: “What are you, a schmuck?!”

Now, although I am certain its nuance escaped me the first time I heard it, when I was perhaps eight years old, I did likely understand, thanks to the shibboleth of its final epithet, that what my father had told was a Jewish joke. And what I have come to realize about Jewish jokes is—that they are not always funny: that they are often more akin to Zen koans than to thigh-slappers. Jewish jokes may require more cultural literacy than is needed to appreciate the average crack; indeed, they may be explicitly deployed to signal in-group membership. Recall this bitter definition: An antisemitic remark is a Jewish joke told by a non-Jew.

Jewish jokes, by this token, may thus begin to look more like dad jokes than like classical standup humor. Not that Jewish jokes are never sexist, of course—think of their stock female characters, the castrating mother and the asexual wife, and of how they codify a heteronormative, cis-masculine perspective; nor are they never violent—there’s the one about the Jewish kid who is beaten by his family for converting to Christianity, for example, who then wonders at how quickly a gentile can become an antisemite. And as for racism, the classic Jewish joke is virtually predicated on an essentialist construction of cultural tradition.

What makes the best Jewish jokes “unfunny,” in the conventional thigh-slapper sense, is their reliance on irony, on an awareness of the coexistence of two different and possibly mutually exclusive, even contradictory states: autochthony and exile; acceptance and rejection; affiliation and alienation. As in the one I heard my dad tell when I was young, about the survivor angrily confronting the magician on the Titanic, who is adjudged to be powerful enough to sink an entire ocean liner, and at the same time so petty that he would endanger his own life for a stage effect. Then there’s the one about the man, following another shipwreck, who recreates the divisions allegedly typical of his community in a wholly solipsistic version:

A Jew has been marooned on a desert island for ten years before a ship recognizes his flag of distress and sends a boat to rescue him. “Let me show you around,” says the Jew to the men who come ashore. “Over here is a synagogue. Next to it is my house. And next to that is a barn I built for the animals I was able to domesticate. Over there’s the synagogue I built for myself–” “Just a minute,” says one of the men, “you just pointed out a synagogue back there.” “Ach,” says the Jew, “I don’t go to that shul!”

Or take the one about the men in the woods, who live in a symbiosis featuring a world navigable with philosophical speculation, and a world governed by physics. The joke, included in my father’s collection but which I first heard my German-Jewish uncle tell, owes as much of its ironic effect to the nuances of a foreign (Yiddish) punchline as to its dual cosmology:

Three Jews are driving through the Black Forest in a horse-drawn cart. As the road winds around a curve, they find that a large tree has fallen and blocks their path. They pull their cart over to one side and study the log. Then they sit down and begin to discuss how to deal with the situation. They adduce the theology according to Mishna; they cite Maimonides and even Spinoza; they consider the social and political implications… This goes on for several hours, until another cart comes around the curve and stops at the log. The burly German coachman leaps off the cart, walks over to the log, puts his shoulder under it, heaves it aside, and continues on his way. As he disappears down the road, one of the Jews turns to the others and sneers: “Kunshtuk—mit gevalt!” (“Big deal—he used force!”)

And then there’s the one about Goldberg, who has lived in earthly poverty for years but who now, hoping for otherworldly intervention but failing to see the interconnection of the two ostensibly different realms, goes to the synagogue:

“God,” prays Goldberg, “I’ve been a faithful Jew all my life. I’ve never asked anything of you in return. For years now I’ve been hoping to win the lottery. Would it be so bad if just this once you arranged for me to strike it lucky?” After a while he hears the voice of God call out to him: “Goldberg,” says God, “do me a favor—buy a ticket!”

The irony that is the motor force of the best Jewish jokes also often arises from the simultaneity of two disparate times, the ancient and the modern: as in this one, about the transmission of an ancient text into a modern world, and its relative intelligibility there:

One Passover, a religious Jew sits down on a bench in Central Park to eat his lunch. A few minutes later a blind man sits down beside him. “Can I offer you a bite of my lunch,” the Jew asks. “That would be very nice of you,” the blind man replies, whereupon the Jew hands him some matzoh. The blind man fingers it for a moment and then asks: “Who wrote this nonsense?!”

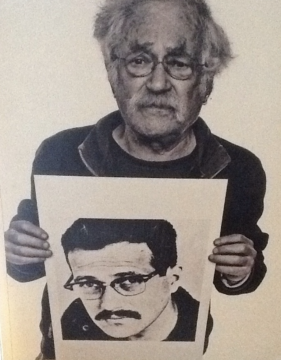

Or as in the photograph of my father at the head of this text, taken in a series of portraits of people exhibiting an image of themselves at their ideal age. In my father’s portrait, made around the same time as he bequeathed his collection of jokes, as he was approaching the age of 80, he holds his author’s photo from the dust jacket of his first novel, We Always Take Care of Our Own, published in 1965 when he was 30 years old, a young man with a burgeoning family. This avatar, at the outset of his career, both as an author and as a father, when he still had a story to tell, thus coexists with the present image of himself, haggard and melancholy and no longer able to narrate, yet preserving, somewhere within him, the glint in the eye of that aspiring joke-teller.

Here is an enactment of the original meaning of irony, which is derived from the actor’s craft of dissimulation, of the donning of a mask: the old man displays a mask of himself half a century ago, even as he maintains that the face he wears now is the actual mask. Funny, but no laughing matter.

*

My father had little time for the current affairs of his native Canada. He was an inveterate follower of American politics, and he cultivated the same interest in me. To this day I can name all the 20th and 21st-century US presidents, while I am shaky on Canadian prime ministers; and in the mid-1970s, while my prepubescent peers were reading The Lord of the Rings, I was immersed in All the President’s Men, a dog-eared copy passed on to me by my dad (who had borrowed it from his similarly obsessed father).

The attention my father paid to American civics was accompanied by equal parts admiration and revilement, the former for Cesar Chavez, Pete Seeger, or MLK, the latter reserved for the likes of J. Edgar Hoover, Nixon, and George W., as well as for the outrages of institutional racism, Vietnam, Watergate, and Iran-Contra. So when Donald Trump emerged on the presidential stage, my father was soon predictably, morbidly fascinated—although in this case what preoccupied him were not the putative virtues or vices of that unlikely candidate for high office, but rather the inscrutability of Trump’s interior life.

I wonder what dad would think these days, as Trump’s psychology is increasingly on display, especially in contrast to his new rival for the presidency, someone whose relative age and vigor make the differences in their temperaments that much starker. In particular—because Trump himself has focused on laughter, in his bestowal on his opponent of the nickname “Laffin’ Kamala”—there is the suddenly egregious fact of Trump’s own evident refusal (or inability) to laugh. Kamala Harris, of course, is currently being celebrated (or ridiculed) for her ready and abundant laughter, which is interpreted by her admirers as evidence of self-possessed subjectivity, and by her opponents as proof of frivolity and distraction—or as the sign, although this is naturally not made explicit, of the feminine abject, this last presumably held to be the opposite of Trump’s own, un-laughing self-mastery. Laughter, in this latter, pejorative interpretation, signals insufficient autonomy, wordless kowtowing to the speaking subject: like Trump’s own audiences, who are regularly expected to roar with laughter at their idol’s “jokes” while he himself remains grimly unmoved. It seems that Trump, by resisting laughter while doggedly attempting to elicit that deprecated response from his audience, is obeying the dictates of a traditional masculinity, which sees in laughter, despite its apparent enactment of an aggressive posture (bared teeth, hooting), a gesture of submission: of femininity.

The problem for me is that this interpretation also accords with a certain construction of Jewish jokes, which, as noted above, may certainly be infected by toxic masculinity. Salcia Landmann, the late Swiss doyenne of Yiddish literature, included the following meta-joke in one of her several studies of Jewish humor:

How many times does a peasant laugh when you tell him a joke? Three times: once when you tell it, once when you explain it, and once when he gets it. And how many times does a Jew laugh? He doesn’t. He tells you he’s heard it before and can tell it better.

In other words: the master teller of a Jewish joke is a male Jew who does not laugh; its hearer, and eventual appreciator, is a member of a dominated group.

And in fact, one of the oldest Jewish jokes features precisely such a constellation. In Genesis, when Sarah hears that God has announced her impending production of a child by her husband Abraham, she laughs, since her advanced age makes a joke of the suggestion. The punchline, of course, is that she does indeed become pregnant and bear a child, whose name is a verbal commemoration of her response: Isaac (Yitzchak) is derived from the same root (tzachak) as the Hebrew word for laughter. Thus, in this primeval instance of Jewish humor, a male figure tells a joke—a female figure laughs—and her response, although in the moment evidence more of derision than of submission, is crystallized in the very sign of her own deployment as a tool for the construction of the Jewish project.

Now my father, who was himself known to respond, in the classically Jewish way, to an already familiar joke with a deadpan stare, could in fact also be seized by laughing fits, virtual paroxysms of joy that transformed his face into the likeness of his cheerful Ukrainian-Jewish mother, whose susceptibility to laughter leavened the traditionally masculine stoniness of her Polish-Jewish husband, my grandfather. And one of my father’s fondest memories of a formative episode in his coming of age as an adult Jew is of laughter—the laughter of a man.

In the mid-1950s, when he was in his early twenties, my dad spent some time on a kibbutz in northern Israel, practising the ardent Zionism he had inherited from his father but which would become tempered, in his later years, by horror at the development of the Jewish state. During that early sojourn he was hosted by an older couple, long-time inhabitants of the kibbutz who had “adopted” him as their temporary son while he was a resident there. What my dad recalled with especial pleasure, and recounted to me on several occasions, was a discussion concerning literature he had had with his host “father”, in which the man had told him that he particularly enjoyed reading A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh (or “Veenee ha’Puh,” in my father’s memory of the Hebrew title)—“because when I read it,” my father remembered him saying, “I laugh, and I laugh, and I laugh!” And my father would repeat the phrase he had heard in Ivrit at the time: “Ani tzochek, v’ani tzochek, v’ani tzochek!”

So there it was—tzochek —the same root (tzachak) as in the name of the patriarch Isaac, the commemoration of a scornfully laughing woman who becomes the butt of her own joke, now transformed into the admission by a (Jewish) man that he can indeed joyfully submit to the humor of another.

As for Isaac, a testament to a mother’s laughter, and his subsequent, horrific role in the mythical history of the Jewish people: my father would often say that he could never accept a deity who demands the sacrifice of a child—as God does of Abraham, when he commands him to bind Isaac—even if, or perhaps precisely because, that demand is then twisted into the punchline of another, even crueler joke—when at the last minute God substitutes a ram for the bound child, in the first, and worst, of all dad jokes: “When I said kill a kid, I didn’t mean that kind!”

For all that my father continued throughout his life to yearn for a congenial connection to his ancient, inherited faith—he would occasionally refer to himself as a “lapsed atheist,” and in his final years he began to say “God bless you” at the close of an encounter, a novum—dad could not reconcile himself to his own father’s stern religion, with its cold, brutal, distant Almighty, a punisher of the very laughter He had elicited and a tester of His “chosen people” in a series of calamities that would eventually coalesce into a grim joke about every Jewish holiday: “They tried to kill us. We survived. Let’s eat.”

The love that I shared with my dad, meanwhile—whether expressed casually, solemnly, from afar or up close—well, that was no joke.