by Angela Starita

New York magazine published a story about two sisters who decide to leave civilization and try surviving in the outdoors of Colorado. One has a 14-year-old son, and she brings him too. In fact, much of her motivation appears to be protecting him from dangers she perceives, existing ones and more she believes to be just on the horizon. The writer doesn’t know many of the specifics of those fears, but from text messages, she gleans that the mother, Rebecca Vance, believed that the world was on the verge of collapse and wanted to escape the ensuing survivalist brutality. Instead, the three died of malnutrition and hypothermia probably within two months of going “off grid.” In short, in trying to outrun anticipated violence, they instead faced a grueling, attenuated death.

People quoted in the article attest to the sisters’ clear lack of familiarity with the backwoods camping let alone how to build a shelter, gather or grow sufficient food, generate heat, and all the other essentials to assure long-term survival. That aside, though, the sisters were acting out a typical response to their fear of the encroaching demands of the modern world. In their own panicked, inept way, the sisters were part of a long tradition of runaways looking to escape or reconfigure the rules of society as they understood them. It’s a familiar list—New Harmony, Oneida, the Shakers, even Jonestown—born of a familiar impulse: to start over and this time get it right.

Almost everyone I know has had a similar fantasy, though my family’s version were more akin to Unabomber than communitarian. My mother often talked of running away to study at the Culinary Institute of America under an assumed name, Beatrix Jones. (That she told us the name considerably allayed any fears we might have had about the seriousness of the threat.) What happened after graduation from CIA was never revealed, but I presume she’d have taken an apprenticeship under a patisserie chef, perhaps in France, and eventually started her own renowned shop. But all this was hardly an option since she was much too busy supporting my father’s actual escape from years of work that he despised. In his 50s, he closed his small store in Jersey City, and he and my mother bought a 10-acre plot of land in central New Jersey, an area of small farms and beat-up horse ranches, and he began farming. He kept up the farm for a dozen years before he’d had enough of that much work and daily isolation.

Among my own friends is a running discussion of what we should do when we retire. Almost all of us are childless and worried about our old-age fates with blood relatives in short supply. I am an advocate for the compound solution: a bunch of prefab houses on a shared piece of land purchased now with one extra house for communal meals and housing guests. (Admittedly, I took my idea from ones adopted by groups of women in the late 19th century wanted to cut back on duplicated chores by organizing families into collectives and sharing the workload—cooking, laundry, marketing, etc.) A friend thinks we should pool our money and buy small apartments in different parts of the world to use at will, a self-selected timeshare that, while far more fun than a prefab commune, wouldn’t address the bigger needs for community and assistance. A few have tried to identify affordable small cities where we could each buy a home or apartment but be within walking distance. Another thinks we should more realistically aim to be within the same county as each other.

Our goals are practical ones and have nothing to do with religion or political beliefs though our socio-political commonality was part of the essential glue that brought us together in the first place. But what we have in common with the famed utopian towns of the 19th century is a dread of isolation. This is what drove much of the thinking of French social philosopher, Charles Fourier, who lived through the French Revolution and through his theories tried to impose an order in an era of exceptional chaos. “There must exist a unitary social code, founded by God and revealed by attraction,” he wrote in his first book, Theory of the Four Movements (1808).

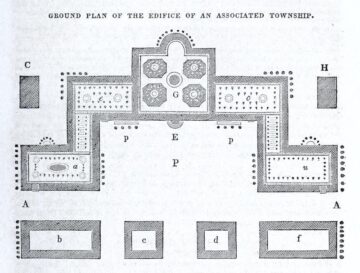

He argued that while human beings have had periods of progress in their thinking, by 1800 we were stymied, regressing even. A clear symptom was the traditional family structure, which as he saw it, detached people from society at large, while encouraging competition and rivalry. He reckoned that love and companionship depended on a communal arrangement but not one determined by bloodlines. Instead, he advocated for limited-sized communities—phalanxes, he called them—organized so that residents could pursue “affinities,” that is, doing the work they were drawn to, not imposed by hereditary or economics, a nineteenth century version of self-actualization. Religion played no part in the Fourier scheme, neither did class.

By the 1830s, Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune, among others, started to advocate Fourier’s version of utopia, seeing in it a flexibility suitable for Americans looking to escape city centers but live within a community. Between 1830 and 1860, 28 phalanxes were founded across the country, and most failed within five years.

Unlike the Shakers, for one example, who quashed individual desire to the will of the community, the phalanxes were predicated on fulfilling desires, at least in terms of vocation. There was no requirement to stay separate from the world outside the phalanx. In fact, the economics of most if not all of the American communities was dependent upon outside investors, people who believed in the movement but didn’t live in a phalanx. According to one historian, the community’s economics usually caused the phalanxes to fail, in part due to poor planning and failed crops, in part because shareholders who’d underwritten the purchase of land or building materials wanted–felt they deserved–more input than members who couldn’t contribute financially. Without the glue of religious credo or a political one, the phalanxes had a difficult time retaining members once an organizational disagreement arose. (The phalanxes reminded me of the words of Mon Dat Chan, a man I once interviewed about the amateur Cantonese opera club he ran in New York’s Chinatown. He explained the one-time abundance of such clubs in Manhattan simply: if a man didn’t get a leading role in one club, he’d leave and start his own troupe.)

Arguably the most successful of the American phalansteries was set about a fifteen-minute drive from my father’s farm. All that remains of the North American Phalanx is a road name in Colts Neck, NJ. My father drove on Phalanx Road hundreds of times on our way to the beach in summer. It was a weird name, for sure, but mostly forgotten until I’d read about Fourier and his phalansteries. The group’s whole venture lasted for about 12 years. closing in 1856 after a fire. I read that one of its buildings remained on the property until the mid-1970s when another fire destroyed the last physical trace of the movement in the United States. Ironically, Fourier does live on in the built environment, but one that would be wholly alien to him: Le Corbusier, the architect-genius who arguably is most responsible for our notions of modern architecture, relied on Fourier’s ideas to inform the designs of his residential apartment buildings, most notably one he called the Unité d’habitation, a name to capture the wholistic quality of the project. They were to be fitted with shops, nurseries, gyms, what he called “streets in the sky,” and gardens, vertical phalansteries.