by Richard Farr

This is the second part of a three-part essay, My Drug Problem. Part one, A mere analogy, is here.

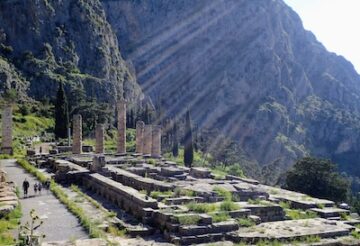

Your life is not going according to plan and you’ve started to wonder what the gods are playing at. Still, the decision to consult the Oracle at Delphi is not one you took lightly. First you tried all the usual remedies: drinking too much, blaming other people, listening to soothsayers in the agora. Only when none of this helped did you undertake weeks of travel to reach bucolic Phocis, finishing with an arduous climb to this shoulder of rock a thousand feet above a valley in the middle of nowhere.

At least the views are nice. On a goat track that will one day be a narrow street clogged with over-fed barbarians in tour buses, you stop to ease your blisters and gaze down towards the Gulf of Corinth. Lovely — you’d take a picture if you could. Mount Parnassus looms behind you. Five minutes later you’re at your destination.

The Temple of Apollo is an important religious center, so you’re surprised to find it painted all over with self-help graffiti: Wherever you go, there you are. If life hands you lemons, make lemonade. The journey is the destination. Life is uncertain; eat dessert first. Over the main entrance, the message spray-painted on the lintel is marginally more enigmatic than the rest: Gnothi s’auton, anthro — Get to know yourself, man.*

(* Shortly after your visit, part of the lintel will fall off in an earthquake and the “man” will be lost to history.)

As you’ll soon find out, opinions differ about where these pearls originate, but all you’ve heard is that they are quotes from the Oracle, or Pythia, herself. She lives alone in a nearby cave, meditating among theogenic vapors, and inhaling the divine funk has resulted in all manner of mystical insight. So it’s natural for you to understand know yourself as essentially a sales pitch: “Come on in! Better wisdom through chemistry! No need for the hard work of trying to make sense of life on your own. The Pythia will hand you all the self-knowledge you could ever have, or want, simply by telling you your fortune.”

The temple itself is only for the ritual sacrifice; you pay a drachm at the entrance and equip yourself with a chicken. After the blood’s spilled, you exit through a side door and follow the signs. A path leads through the gift shop, with its display of plush-toy deities, to a fissure in the side of the mountain.

Steps lead down into the ground. You inhale deeply as you descend, surprised a little that the gods smell so powerfully of rodent. Eventually a cavernous space opens out, and in it a fire casts suggestive shadows on the back wall. These shadows are fascinating in themselves and also remind you of a story you once heard in Athens; you’d like to take a closer look. But just as you’re noticing that one of the shadows looks a lot like you, only sexier and more self-confident, a figure in a thin khiton emerges from the darkness, carrying with her a deranged smile and a pet crow. It’s the Pythia.

No introductions. Eyes fixed on you, she sways rhythmically, jabs at her hair with bony fingers, and starts ululating. (For obvious reasons, it does not occur to you that she’d make an excellent witch in Macbeth.) The performance goes on for several minutes, getting louder and more extreme. It’s shocking when she stops without warning; it’s even more shocking when, in the ensuing silence, she uses an ordinary, matter-of-fact voice to reel off a list of facts that you’re unsure you wanted to know.

You will become rich, she says (or poor). Your children will love you (or only be good at pretending). You will be healthy (or sick). You will discover joy and fulfillment in your work (or only drudgery and a sense of failure). Your death will come for you on this date, early but kind — and then change its mind at the last second and come back again on that date, late but cruel. Oh and BTW there are seventeen dimensions, not three, time isn’t what you think it is, by far the most momentous decision in your life will be an apparently insignificant one, and the Elysian Fields await you after death but only briefly because after that you will be reincarnated as a frog in a rainforest on another planet.

Because nobody has ever suggested otherwise, you believe every word. It’s all too much — it always is — and you retreat to a bar to cry into a krater of wine. (By astronomically improbable coincidence, the spot where you’re sitting will one day be inside the Delphi Archaeological Museum and this same krater will also be in this same spot, inside a glass case, gawked at by the barbarians you didn’t meet earlier.)

When you share your woes with another barfly, he slaps you on the back and says you’ve got it all wrong. “The graffiti-author wasn’t the Pythia, dummy. It was Chilon.”

“Who?”

“A Spartan philosopher. Kick-started the city’s reputation for laconic wit by declining to communicate at all except in T-shirt slogans.”

You notice that the barfly is wearing one: Your trireme is safer in port. But that’s not what triremes are for.

“What’s a philosopher?”

“Surprised you don’t know that, coming from Athens — it’s the latest thing. They don’t believe in the gods, or divination. According to them, the Pythia’s high as a kite and talking BS. The only way to know yourself is by reasoning logically about the Nature of the Good.”

Thus dawns your first hint of skepticism about the Pythia, and with it a new phase in your life. Two weeks and several pairs of sandalia later you’re back home in Attica and you dive with enthusiasm into this hip, cosmopolitan new subculture of drinking espresso while Thinking Stuff Through from First Principles. Sure, say your new friends the philosophers, a plausible strategy for being happier is to understand your own nature better — but you can’t find that out from oracles. You need to think for yourself! And a black belt in thinking starts with X’s lectures about meaning and verification, Y’s seminar on the syllogism, and Z’s regular symposia (BYOB) on the metaphysics of personal identity.

You do all this. You even enjoy some of it. Eventually, inevitably, you run into Plato, who you recognize as the lad from way back with the cave story. Plato has taken old Chilon’s idea and run with it. Actually, not run with it so much as tucked it under his arm, sprinted for the logical touchline, and carried on sprinting right past the hot-dog stand and out of the stadion. (No one can stop him; big shoulders, Plato.) That a morsel or two of self-acquired self-knowledge might be a good idea he dismisses as milquetoast and feeble. He turns it on its head, and argues that any life that fails to be dedicated to self-knowledge isn’t even worth living. Also (roll of drums here: a big fluffy rabbit is about to come out of the hat), since philosophical reasoning is by definition the royal road to self-knowledge, your only possible true course in life is to toss your comforting illusions, quit the cave of unreason, and emerge blinking into the sunshine of Knowledge. (“We don’t call it enlightenment for nothing!”)

You buy the whole intellectual package and in no time you’ve joined the faculty. You write. You give lectures to herds of younger people who earnestly write down every hare-brained idea that drifts into your head during another fifty minutes that you didn’t really prep. You go to conferences and hob-nob with the big names in neo-constructivist epistemology. You even become something of a public intellectual, acquiring several thousand followers on PapyrusⓇ. Years pass, and from time to time you look back with amusement on the rube who believed in divination and hoofed it all the way to Delphi.

But not all is well in PlatoWorld. Your skeptical doubts keep invading the home of skepticism itself. For one thing, you’re surrounded by the roar of people who obviously find the unexamined life an absolute riot. For another, many of your fellow converts to the examined life seem privately disappointed by its ROI. (A recurring nightmare about this involves a dinner at Plato’s. You’re seated between two oddly-dressed men who speak the same bad Greek. They are miserable, and clearly hate each other. The one on the left talks your ear off in an attempt to prevent you from listening to the one on the right — and vice versa. Their names are Hegel and Schopenhauer. You wake up screaming.)

And then there’s the fact that philosophy is just one among many competing strategies for self-revelation. Many Athenians are making art, for example, including painting, poetry, and tragedy. The official doctrine in the Church of Plato is that this is a doomed strategy — as bad as getting plastered (the “Alcibiades option”) or listening to cave-dwelling god-botherers. “It only promotes irrationality,” says Mr. P. “Banish the suckers. In our ideal society, which we will be running by the way, we want people to come to conclusions about how things are, not waste time and confuse people by merely representing the way they seem.” One of the better grad students, name of Aristotle, disagrees mildly: he wants to argue that art can be useful. Though only as a kind of emetic.

Something about all the violent, rhetorically charged hatred of any allegedly irrational investigation, in the name of Reason but in face of so little evidence that the reasoning has actually improved your mileage, nags at you more and more. Delphi is many years past, but all your old self-questioning and dissatisfaction are flooding back. You’re starting to feel that the whole philosophy lark has been a bait-and-switch, actually. You’ve met many people who describe themselves as Enthusiasts for the life of reason, but that strikes you more and more as an odd choice of word. (Entheusiazein: (1) inspired by the gods; (2) bat-shit crazy). In any case, at vanishingly few points in all your reading and degree-getting have you encountered more than faint, vanishing whispers of interest in anything that deserves to be called wisdom about the nature of the self — even among the people hunched over their manuscripts who are allegedly specialists in the art of living, hē ēthike tekhnē. Surely somewhere there is an easier way than this of making progress?

Far later in life than it should have, frustration brings you back full circle to the irrational forces at work in the Pythia’s cave. Not that you’re interested any longer in hearing someone else tell you what they think the gods are saying. But if you could only breathe that musty air one more time? And be left in peace to draw your own conclusions among the shadows? What if you could cut out the middle-woman, and find your own chemical shortcut to the voices of the gods?

Not telling any of the Platonists, who you fear would either be shocked by your apostasy or scoff at your folly, you skip the departmental meeting one day and wander out into the countryside. Today you are seeking advice from a very different woman. By a coincidence less astronomical than the bit about the krater in the museum, she also wears a thin khiton and has a pet crow. But she is a mushroom-hunter.