by Deanna Kreisel [Doctor Waffle Blog]

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

The other day, over cigarettes and beer, my friend M. told me the story of the Ghost Cop of Rowan Oak. She was speaking from authority, as she had just encountered it a few days before. Her boyfriend P. was there—both at Rowan Oak and on my front porch with the cigarettes and the beer—and it was nice to watch them swing on the swing and finish each other’s sentences.

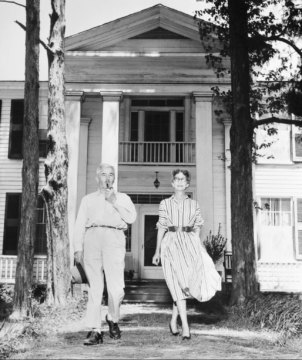

It had all started innocently enough: the two of them had decided to take their dogs C. and Z.[1] on a late-night stroll through M.’s neighborhood, which happens to contain a large antebellum estate known as Rowan Oak. For the benefit of the 99.999% of this publication’s readers who do not live in Oxford, Mississippi: this particular large antebellum estate was home to William Faulkner from 1930 to the time of his death. For the benefit of the 0.001% of this publication’s readers who do not know who that is: William Faulkner was one of the greatest American novelists of the twentieth century, an early practitioner of the subgenre that came to be known as “Southern Gothic,” and a lifelong resident of Oxford who wrote about the town and surrounding area (fictionalized as “Yoknapatawpha County”) in 16 novels and over 50 short stories.

So M. and P. were strolling the other night with her tiny adorable dog and his larger adorable dog, enjoying the delicious bosky springtime air, when they made the fateful decision to extend their walk to the grounds of Faulkner’s estate. They were chatting away when they passed the invisible property line, at which point they were immediately assaulted by a brilliant search light splitting the darkness. A disembodied voice—they couldn’t see the speaker, since he hovered in the dark behind the light—demanded to know what they were doing on the grounds of the estate, which was closed for the night. [N.B. there was no Hours of Operation indication at the time, although a brand-new sign has since mysteriously appeared right on that spot.] M. and P. apologized profusely and were backing away from the bright light in their eyes when the voice went on: “You know, there are a lot of good reasons not to walk around this place at night. I mean … I’ve heard stories.”

P. was pretty sure he wanted to get out of there immediately, but M. was now intrigued. “Oh? Like what?”

“Well, it hasn’t happened to me personally, but to a lot of colleagues of mine. A lot. Voices, lights, other-worldly things in the woods.” The cop voice was clearly eager to talk. “And I’ll tell you what. I haven’t seen ghosts here, but I have definitely seen them.”

They were obviously settling in for a good long chat here. M. encouraged him to go on. “Really? Like…?”

“Well, I haven’t had a lot of experience with this ghost myself, but there is one in the house we moved into a few years ago. My wife, my daughters, my mother-in-law—they’ve all seen it a bunch of times.”

“Oooooh! What does it look like?”

“She’s an older lady, wearing a pink paisley zip-up house dress. Her hair is salt-and-pepper”—his voice dropped to a conspiratorial whisper—“I’m going to say more salt than pepper, if you know what I mean.” M. was tickled that he was being chivalrous about the age of the ghost. “And her hair flipped up in the back, like she had just put in that one row of curlers.”

By this point their eyes had become acclimated to the search light, and M. and P. noticed that the cop himself was a portly gentleman, completely bald. As M. later put it, “like a child’s drawing of a man, with one big circle for the body and a smaller circle on top for the head.”

He went on about the ghost. “My daughters and wife always see her on the stairs. I’ve never seen her myself, but I have heard the noises. And I believe them. Their stories are always consistent.”

It seemed like that was all the ghost intel they were going to get out of him, so M. and P. started edging away, trying to make their escape. But the cop told them he was bored and happy to finally have someone to chat with. Clearly they weren’t going to get away that easily.

“I should introduce myself, by the way! My name is Sidney Austin. Yeah, it’s a funny name, right! A while back I was busting up a party with a bunch of underage co-eds and one of them told me she was from Austin, Texas. So I leaned in real close so she could see my badge and kept asking her to say where she was from. Finally she noticed that my name was ‘Austin’ and she thought that was real funny!”

M. and P. were privately skeptical about how funny the young woman found the coincidence. They themselves were starting to feel a little trapped by this bulbous officer of the law, worried he was about to turn aggressive or even creepier, longing now to get away. At this point they’d been talking to this guy for what seemed like an eternity. They noticed that his car didn’t really look like an official police car, but was just a regular SUV with a light on top. They finally started walking sideways back toward the entrance to the estate, edging away from the voice that kept talking to them out of the darkness.

The next day M. told this story to our mutual friend S., who immediately went to the City[2] of Oxford website and looked up Sidney Austin on the local police department roster.

And…

He was not listed.

Obviously—and this is the only logical conclusion one can draw—Sidney Austin was a ghost cop. Clearly the whole “I have a ghost in my house” thing was a ruse meant to distract M. and P. from the obvious fact that he himself was a supernatural being. A phantom policeman—poltergeist gendarme, revenant flatfoot, banshee bobby, gumshoe shade, specter narc, spook spook—doomed to roam the grounds of Faulkner’s estate for all eternity. Who knows what crime he was sent from beyond the grave to avenge? What terrible unfinished business disturbs his eternal rest? What torturous question he seeks to answer, what awful mystery he is forced to solve? Whose soul he must seize in order to slake his bloody thirst for vengeance?[3]

Ghostly Interlude 1. I had been working on this essay for a while when it occurred to me that there might actually be some legends or lore about ghosts at Rowan Oak. A typical 21st-century researcher, I took to Google and typed in “ghosts rowan oak,” and immediately came across a book entitled, well, The Ghosts of Rowan Oak. (Sometimes Googling makes you feel like you might be living in The Matrix.) The book is a collection of “William Faulkner’s Ghost Stories for Children” and was written by Faulkner’s niece, Dean Faulkner Wells, in 1981. I sent the Amazon link to my friend M. with a message that read only “!!!!!!!!!!!!!!” and seconds later she texted back and asked if I wanted an introduction to Larry Wells, Dean’s widower. Of course I said yes. Literally within minutes of this thought occurring to me—this possibility of there being stories about ghosts at Rowan Oak—I had set up an appointment to meet a local Rowan Oaks ghost expert at Rowan Oak in three days’ time. Oh Oxford.

After M. and P. had finished telling their story on my porch swing the other night, we sat in silence for a few minutes and listened to the strains of a marching band echoing across the park between our house and the local high school football field. Early-summer shadows crept over the overgrown front lawn as a barn owl in the woods nearby started tooting its accompaniment. Finally I asked M., who is also a brilliant novelist and poet residing in Oxford, Mississippi, how she felt about encountering a ghost on the estate of one of the most important American novelists of the twentieth century. Did she even believe in ghosts? Did she think the cop was there to send her a message, maybe from Faulkner himself? I could barely make out her dark eyes in the gloaming as she contemplated my question. She smiled slightly and didn’t answer.

Ghostly Interlude 2. Since my appointment with Larry Wells was coming up so soon, I had very little time to acquire and read a copy of The Ghosts of Rowan Oak before our meeting. I was able to buy a copy immediately at our local, excellent Square Books, and took it with me to the Mississippi Book Festival in Jackson, where I was spending the two days between Googling “ghosts rowan oak” and meeting with the Rowan Oaks ghost guy. At the festival there was a little pop-up library room that Mr. Waffle and I wandered into between panels; one of the displays featured a game-show-style wheel with pictures of Southern authors pasted on it that you were invited to spin to find your literary soul mate. My spin landed on Willie Morris, and I was handed a little slip of paper with facts about his life on it. Scott (Mr. Waffle) then spun the wheel and also landed on Willie Morris. “No no no,” he said. “We can’t both have the same one!” He spun again and landed on … Willie Morris. Subsequent spins: Spin Again and Willie Morris. “Jesus!” I almost shouted at him, starting to feel a little creeped out. “Clearly Willie Morris is your guy! Don’t mess with The Wheel, dude—just accept it.” He insisted on spinning again and finally got someone else. I felt a little shaken, and we hustled out of the library display room pretty fast. I am superstitious. We found an unoccupied leatherette bench in a quiet corner and settled down to wait for the next panel. I pulled The Ghosts of Rowan Oak out of my bag and started to read. “Introduction.” My eye paused. I felt a little tingle down my spine and was suddenly reluctant to scan down the rest of the blank half-page—but somehow I already knew. “By Willie Morris.”

The next day I hightailed it from the Mississippi Book Festival in Jackson back to Oxford in order to make my appointment at Rowan Oak early Sunday afternoon. As soon as I entered the foyer of the big house I was greeted by the assistant curator, Sarah, whom I informed that I was meeting someone for an interview. I stood awkwardly in the entryway for a few minutes as I waited for Larry Wells, who was late. Finally I decided to explain why I was there and ask Sarah if she had any information about ghosts or hauntings in the house. Did she ever! The first thing she told me was that ghost hunters contact the estate all the time—particularly around Halloween—to ask if they can spend the night to conduct research. They bring tons of fancy electronic equipment and hunker down with their instruments, hoping that overnight they will catch vibrations or electromagnetic fields or whatever constitutes evidence of supernatural activity. “Has anyone ever found anything?” I asked. “No. No one ever has,” Sarah replied. “We’re kind of done granting permission at this point. I mean, if no one has discovered anything yet, what are the odds that anyone will in the future?” “Good point,” I replied. There’s either a ghost there already or there isn’t—it seems unlikely that a brand-new one is going to suddenly materialize. Sarah then told me that regular visitors pull out their phones all the time and scan for ghosts using an app you can download. Of course they do, I thought.

Only then, almost as an afterthought, did she inform me that the current curator had his own ghostly encounter a while back. During some renovations on the estate—which was built in the 1840s by a Tennessee planter and almost certainly housed enslaved people in separate quarters—the curator had taken some photographs from the top floor of some outbuildings in the back. When they were developed, one of the photos contained a blank spot right in front of the servants’ quarters; in the blown-up version you can just make out a blurry ghostly figure hovering in the foreground.

Ghostly Interlude 3. Half an hour and still no Larry Wells. A tiny unbidden thought tickled the edge of my brain: Maybe he’s just died! What a hook that would be for my essay! But of course I didn’t allow the tickle to develop into a wish, or even a speculation. It was just an idle thought. I’m not a monster. I eventually texted Larry Wells that I was going to head home in a bit if he wasn’t able to make it, kind of wishing I’d slept in that morning in Jackson. There was no reply. As of this writing I have yet to meet the widower of the niece of William Faulkner in the flesh. That is (dunh dunh dunh)—if he even has a fleshly presence.[4]

As I chatted with Sarah for a while longer, I got the sense that she was trying to figure out if I believed in ghosts myself. It’s always possible that I was a benign crackpot. I assured her that I was interested in people’s fascination with the spirit world, but I wasn’t a believer. I said I thought it was intriguing how desperately people wanted to believe that there ghosts at Rowan Oak. She agreed. “But you know,” she said, “it kind of doesn’t matter if there are actual ghosts here or not. The whole South is haunted. People just want it to be literal.” “Yes,” I replied. “That’s kind of the hook of my essay. You got it right away.” And then I wondered if I even needed to write it down because it was so obvious, to her and to me—to anyone reading this, maybe.

Right as I was deciding to give up on Larry Wells, the former curator of Rowan Oak stopped by to give Sarah a framed photograph of the house. “The chair of the English department gave me this in 1992,” he explained. “I thought you might want to have it. For yourself, that is—to put up on your wall at home maybe.” She thanked him profusely and as he tut-tutted her gratitude away he turned in my direction and caught me eavesdropping. I apologized and introduced myself as a current member of the English department. He must have thought I was younger than I am since he seemed to encompass both me and the assistant curator—who is young enough to be my daughter—in his apology: “I’m sure it’s boring to hear about the olden days all the time.” I wanted to tell him I’ve been obsessing over the olden days since I was in sixth grade, but he’d already turned to leave. As I watched him drift down the stairs and through the avenue of cedars flanking the entrance to the old house, I wondered if he thought of himself as a ghost.

I headed across the front lawn toward my car and somewhere around the last cedar it finally occurred to me to wonder why Rowan Oak would even have a cop for a ghost. I could think of a lot of haints that would be more appropriate for that particular place: an ethereal housekeeper, perhaps; an alcoholic blacksmith; Atticus Finch; a mule. As far as I’m aware—and please keep in mind that I am a British Victorian novel specialist, not a Southern American literature scholar—there are no ghosts in Faulkner’s fiction. The author of the famous apothegm “The past is never dead; it’s not even past” had no particular use for supernatural phantoms; he had other fish to wrestle, other ghosts to fry.

Faulkner might simply be a product of his time, however. Apparently the number of Americans who believe in ghosts has increased nearly four-fold, to almost 50%, in the past 40 years. By 1983—exactly 40 years ago—an author contemplating writing a novel about a weighty, thorny, tragic, overwhelming topic might more naturally think about including an actual ghost to shadow forth her ideas and themes. Thus the recently unemployed Toni Morrison sat on a pier outside her house thinking about the history of black women in the United States, particularly the impossibility of motherhood under conditions of enslavement, when the ghost Beloved materialized out of the water and strolled across her lawn toward the gazebo. She stood calmly in the shade, sporting a beautiful hat, as Morrison contemplated tackling this overwhelming subject: “The terrain, slavery, was formidable and pathless. To invite readers (and myself) into the repellant landscape (hidden, but not completely; deliberately buried, but not forgotten) was to pitch a tent in a cemetery inhabited by highly vocal ghosts.”

It is possible, however, that there are significant differences between William Faulkner and Toni Morrison other than a few decades between their births.

There are no ghosts at Rowan Oak. That has been proven by science. People desperately want them to be there, but they just aren’t. We wait and watch for them, patiently and reverently, and they never appear. We set aside special times of the year to dress up like phantoms and witches, daring them to haunt us; we paint the ceilings of our porches blue in the hopes that there is something out there that needs to be kept away. Maybe there are a very lucky few whom the ghosts do visit, while the rest of us are left to wander the unhaunted woods, watching and waiting, longing for the chilly touch of the supernatural. Longing for a literal manifestation of the buried, but not forgotten, psychic terrors we cannot face in any other way.

Be careful what you wish for.

[1] Most names have been redacted or changed to protect the innocent.

[2] I don’t know what the technical definition of “city” is, but I think it’s adorable that Oxford calls itself one.

[3] Later we all realized that because the Rowan Oak estate is part of the University of Mississippi, Sidney Austin would have been a campus cop, not a City of Oxford police officer. And indeed his name is listed on that website, plain as day.

[4] He texted later that afternoon to apologize and say that he’d been taking a nap and overslept. Either he is alive and well or the ghosts of Oxford, Mississippi, have started using smartphones just like everyone else.