by Andrea Scrima (excerpt from a work-in-progress)

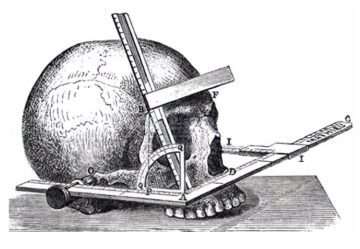

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”

When they arrived in the U.S., Southern Italians brought with them the sense that they’d been branded as underdogs, that they belonged and would forever belong to a lower class, but the birth of the Italian-American gangster was rooted in attitudes toward the Mezzogiorno that dated back far earlier. After Italy was unified under Vittorio Emanuele II in 1861, a new national government imposed Piedmont’s centralized administrative system on the South, which led to violent rebellion against State authority. Politicians and intellectuals took pains to deflect responsibility for what they saw as the “barbarism” of the Mezzogiorno, and were particularly receptive to theories that placed the blame for the South’s many problems on Southern Italians’ own inborn brutishness. The decades following Unification saw the nascent fields of criminal anthropology and psychiatry establish themselves in the universities of Northern Italy; implementing the pseudosciences of phrenology and anthropometry in their search for evolutionary remnants of an arrested stage of human development manifested in the people of the Mezzogiorno, they used various instruments to measure human skulls, ears, foreheads, jaws, arms, and other body parts, catalogued these, and correlated them with undesirable behavioral characteristics, inventing in the process a Southern Italian race entirely separate from and unrelated to a superior Northern race and officially confirming the biological origins of Southern “savagery.”

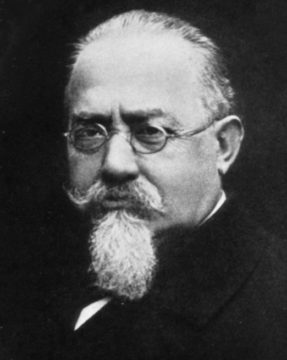

The criminologist Cesare Lombroso, a former army surgeon and head of an insane asylum who became professor of forensic medicine and hygiene in 1878, professor of psychiatry in 1896, and professor of criminal anthropology in 1906, held that the people of the South were “evolutionary throwbacks” lacking in Aryan blood. According to this theory, a congenital inferiority forestalled the mental and emotional development of Southern Italians and was largely to blame for their historical backwardness. Criminality, and particularly the criminality of the South, was therefore hereditary, and identifiable through a specific set of physical traits in keeping with an earlier state of human evolution. Ape-like features such as a low-set brow, long arms, protruding jaw, and other anatomical peculiarities—atavistic anomalies of the body that were closer to a “savage,” animal state—unmistakably identified the “born criminal.”

The criminologist Cesare Lombroso, a former army surgeon and head of an insane asylum who became professor of forensic medicine and hygiene in 1878, professor of psychiatry in 1896, and professor of criminal anthropology in 1906, held that the people of the South were “evolutionary throwbacks” lacking in Aryan blood. According to this theory, a congenital inferiority forestalled the mental and emotional development of Southern Italians and was largely to blame for their historical backwardness. Criminality, and particularly the criminality of the South, was therefore hereditary, and identifiable through a specific set of physical traits in keeping with an earlier state of human evolution. Ape-like features such as a low-set brow, long arms, protruding jaw, and other anatomical peculiarities—atavistic anomalies of the body that were closer to a “savage,” animal state—unmistakably identified the “born criminal.”

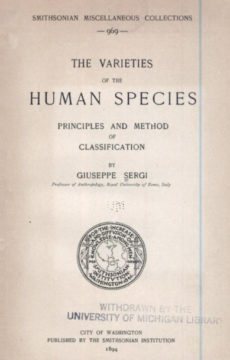

While some criminal anthropologists considered themselves progressives and called for political and economic reforms to resolve the “Southern Question,” the notion of a separate, transhistorical Southern Italian race as an “inferior civilization” tainted by a “criminality of blood” gained ground and provided a handy justification for the economic exploitation of the Mezzogiorno, which was considered incapable of self-government or social reform. One of Lombroso’s followers, Alfredo Niceforo, became a leading figure in the eugenics movement and called for dividing the recently unified country into two governments and two Italies separated by race; another important figure from the Italian school of criminal anthropology was the ethnologist Giuseppe Sergi, who asserted that only cranial morphology, in other words the shape of the skull, and not, as previously believed, the cephalic index or ratio between the cranium’s two diameters, was a reliable measurement in establishing human taxonomy. The Smithsonian Institute published Sergi’s Varieties of the Human Species in 1894, while Alfredo Niceforo’s Contemporary Barbarian Italy appeared in English translation four years later. As impoverished peasants fled the South in search of a better life, the influence of Sergi and Niceforo supplied the nativists, eugenicists, and immigration alarmists in the U.S. with “scientific evidence” that confirmed their worst fears and legitimized their resolve to restrict immigration to a bare minimum.

While some criminal anthropologists considered themselves progressives and called for political and economic reforms to resolve the “Southern Question,” the notion of a separate, transhistorical Southern Italian race as an “inferior civilization” tainted by a “criminality of blood” gained ground and provided a handy justification for the economic exploitation of the Mezzogiorno, which was considered incapable of self-government or social reform. One of Lombroso’s followers, Alfredo Niceforo, became a leading figure in the eugenics movement and called for dividing the recently unified country into two governments and two Italies separated by race; another important figure from the Italian school of criminal anthropology was the ethnologist Giuseppe Sergi, who asserted that only cranial morphology, in other words the shape of the skull, and not, as previously believed, the cephalic index or ratio between the cranium’s two diameters, was a reliable measurement in establishing human taxonomy. The Smithsonian Institute published Sergi’s Varieties of the Human Species in 1894, while Alfredo Niceforo’s Contemporary Barbarian Italy appeared in English translation four years later. As impoverished peasants fled the South in search of a better life, the influence of Sergi and Niceforo supplied the nativists, eugenicists, and immigration alarmists in the U.S. with “scientific evidence” that confirmed their worst fears and legitimized their resolve to restrict immigration to a bare minimum.

Although Cesare Lombroso’s conception of criminal sociology was entirely lacking in any acknowledgement or analysis of the psychological and environmental forces driving human behavior—for instance housing and social milieu, economic conditions, education, professional opportunities, nutrition, climate, culture, and familial influences went entirely unmentioned—, restrictionists seized on Lombroso’s racial theories to support their own efforts to keep out those they considered to be “outsiders of evolution.” Some Lombrosians claimed that the fact of emigration itself reflected a criminal disposition and racial inferiority. Their thinking had a direct impact on American immigration debates even after Italy’s leading intellectuals no longer considered them valid. Sergi’s seminal work The Mediterranean Race was published in 1901 and was read by President Theodore Roosevelt; alongside the work of Niceforo, it later served as a work of reference for the Dillingham Commission and its “Dictionary of Races or Peoples,” which culminated in the Johnson Act of 1921 and subsequently the Johnson–Reed Act of 1924, which drastically reduced immigration through quotas of national origin.

Although Cesare Lombroso’s conception of criminal sociology was entirely lacking in any acknowledgement or analysis of the psychological and environmental forces driving human behavior—for instance housing and social milieu, economic conditions, education, professional opportunities, nutrition, climate, culture, and familial influences went entirely unmentioned—, restrictionists seized on Lombroso’s racial theories to support their own efforts to keep out those they considered to be “outsiders of evolution.” Some Lombrosians claimed that the fact of emigration itself reflected a criminal disposition and racial inferiority. Their thinking had a direct impact on American immigration debates even after Italy’s leading intellectuals no longer considered them valid. Sergi’s seminal work The Mediterranean Race was published in 1901 and was read by President Theodore Roosevelt; alongside the work of Niceforo, it later served as a work of reference for the Dillingham Commission and its “Dictionary of Races or Peoples,” which culminated in the Johnson Act of 1921 and subsequently the Johnson–Reed Act of 1924, which drastically reduced immigration through quotas of national origin.

The immigration of Southern Italians had begun far earlier and at the request of American business interests, however. The emancipation of Black slaves led to a dramatic labor shortage across the American South, and in 1866, the state of Louisiana created the Bureau of Immigration, which began distributing pamphlets abroad to attract prospective workers. The Louisiana Sugar Planters’ Association, comprised of around 500 plantation owners, cooperated with the Bureau of Immigration to send agents to Europe, while throughout the 1870s, more and more plantation owners joined the Louisiana Immigration and Homestead Company to encourage European agricultural workers to emigrate, particularly Southern Italian peasants who were accustomed to heavy labor. The Sugar Planters’ Association succeeded in having a law passed by the state of Louisiana to facilitate the immigration of Sicilians; agreements with steamship companies soon followed to ensure a direct passage from Naples and Palermo to New Orleans. In a strategy the Americans called “push and pull,” Italy passed the “Freedom to Emigrate” law of 1888 as part of a series of bilateral agreements signed by plantation representatives and Italian diplomats to allow for the importation of the labor force they so badly needed. Agents were invited to Sicily to inspect the muscles of young men willing to emigrate; promises were made to pay the cost of the voyage and a handsome salary. In the year 1892, there were 30 immigration agencies and 5,172 subagents in Italy, all of which were involved in recruiting the poor. In 1895, the number of agents grew to 7,109. Villages were inundated with brochures and counterfeit letters from supposed emigrants praising America and the abundance of work and prosperity to be found there, and emigration companies paid between five and 25 dollars to each agent who succeeded in persuading a family to leave. The peasants, keen to finally own land again, were told they would soon be earning enough to purchase their own plots in the U.S. Needless to say, the majority of these promises went unfulfilled.

The immigration of Southern Italians had begun far earlier and at the request of American business interests, however. The emancipation of Black slaves led to a dramatic labor shortage across the American South, and in 1866, the state of Louisiana created the Bureau of Immigration, which began distributing pamphlets abroad to attract prospective workers. The Louisiana Sugar Planters’ Association, comprised of around 500 plantation owners, cooperated with the Bureau of Immigration to send agents to Europe, while throughout the 1870s, more and more plantation owners joined the Louisiana Immigration and Homestead Company to encourage European agricultural workers to emigrate, particularly Southern Italian peasants who were accustomed to heavy labor. The Sugar Planters’ Association succeeded in having a law passed by the state of Louisiana to facilitate the immigration of Sicilians; agreements with steamship companies soon followed to ensure a direct passage from Naples and Palermo to New Orleans. In a strategy the Americans called “push and pull,” Italy passed the “Freedom to Emigrate” law of 1888 as part of a series of bilateral agreements signed by plantation representatives and Italian diplomats to allow for the importation of the labor force they so badly needed. Agents were invited to Sicily to inspect the muscles of young men willing to emigrate; promises were made to pay the cost of the voyage and a handsome salary. In the year 1892, there were 30 immigration agencies and 5,172 subagents in Italy, all of which were involved in recruiting the poor. In 1895, the number of agents grew to 7,109. Villages were inundated with brochures and counterfeit letters from supposed emigrants praising America and the abundance of work and prosperity to be found there, and emigration companies paid between five and 25 dollars to each agent who succeeded in persuading a family to leave. The peasants, keen to finally own land again, were told they would soon be earning enough to purchase their own plots in the U.S. Needless to say, the majority of these promises went unfulfilled.

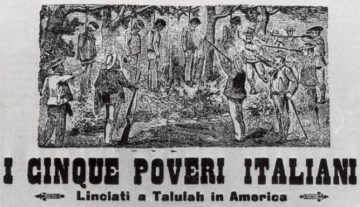

In a mass deportation conceived by two governments, 100,000 Sicilians passed through New Orleans between the years 1880 and 1900. The success of the sugarcane campaign induced the cotton and lumber industries and the railroad companies to follow suit. Attitudes toward the immigrants were initially favorable, but as they left the plantations in search of better opportunities, the mood gradually soured. Due to its seaport, many Italians eventually settled in New Orleans, where they worked in the fishing industry or as seamen, longshoremen, and stevedores and gradually built up a tropical fruit trade. In a startlingly short period of time, they rose from street peddlers to prosperous businessmen in control of much of the growing fruit trade with Latin America. Inevitably, resentment at the Italians’ success led to a rise in prejudice against them. They weren’t especially keen to give up their language or customs to assimilate to the Southern way of life, and because they fraternized with African Americans, they were an affront to the white social order. As Southern Democrats moved toward creating a “Solid South” with a one-party system and white supremacy as its creed, they increasingly began to see the Italians in racist terms. Inflammatory editorials appeared in the local newspapers and acts of violence were committed against the Italian community. As it turned out, the plantation owners had been eager for the white immigrant labor the Italians initially provided, but had never dreamed that the new arrivals would prove to be so thrifty, industrious, and shrewd that they would become independent entrepreneurs in such a short period of time. As a result, Louisiana’s businessmen were determined to curb the competition and curtail opportunities for the Italians’ social and economic advancement. In 1889, a Louisiana newspaper printed a cartoon of a group of Italian immigrants trapped in a cage being lowered into a river with a caption that read: “The Way to Dispose of Them.” Shortly afterward, a mob of thousands lynched eleven Italian-American men. In the aftermath, the Italian government severed diplomatic relations with the U.S., while in Louisiana, an ordinance was passed that put Italian waterfront merchants and workers out of business and handed control of the docks over to an association formed by several of the men who had led the mob.

In a mass deportation conceived by two governments, 100,000 Sicilians passed through New Orleans between the years 1880 and 1900. The success of the sugarcane campaign induced the cotton and lumber industries and the railroad companies to follow suit. Attitudes toward the immigrants were initially favorable, but as they left the plantations in search of better opportunities, the mood gradually soured. Due to its seaport, many Italians eventually settled in New Orleans, where they worked in the fishing industry or as seamen, longshoremen, and stevedores and gradually built up a tropical fruit trade. In a startlingly short period of time, they rose from street peddlers to prosperous businessmen in control of much of the growing fruit trade with Latin America. Inevitably, resentment at the Italians’ success led to a rise in prejudice against them. They weren’t especially keen to give up their language or customs to assimilate to the Southern way of life, and because they fraternized with African Americans, they were an affront to the white social order. As Southern Democrats moved toward creating a “Solid South” with a one-party system and white supremacy as its creed, they increasingly began to see the Italians in racist terms. Inflammatory editorials appeared in the local newspapers and acts of violence were committed against the Italian community. As it turned out, the plantation owners had been eager for the white immigrant labor the Italians initially provided, but had never dreamed that the new arrivals would prove to be so thrifty, industrious, and shrewd that they would become independent entrepreneurs in such a short period of time. As a result, Louisiana’s businessmen were determined to curb the competition and curtail opportunities for the Italians’ social and economic advancement. In 1889, a Louisiana newspaper printed a cartoon of a group of Italian immigrants trapped in a cage being lowered into a river with a caption that read: “The Way to Dispose of Them.” Shortly afterward, a mob of thousands lynched eleven Italian-American men. In the aftermath, the Italian government severed diplomatic relations with the U.S., while in Louisiana, an ordinance was passed that put Italian waterfront merchants and workers out of business and handed control of the docks over to an association formed by several of the men who had led the mob.

(to be continued)

© Andrea Scrima 2023

All Rights Reserved

Read another section of this work-in-progress here.

Information on Andrea Scrima’s first novel, A Lesser Day, can be found here.

Her second novel, Like Lips, Like Skins, was published Sept. 2021 in a German edition titled Kreisläufe. English-language excerpts have appeared in Trafika Europe, Statorec, and Zyzzyva.