by Ada Bronowski

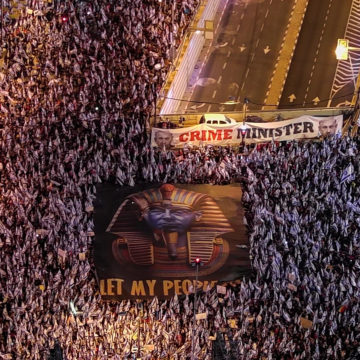

The state of Israel is on the brink of deliquescence. A corrupt multi-indicted prime minister has handed the reins of government to extremist (read: blood-thirsty) right-wing (read: populist imperialist) religious (read: obscurantist) coalition parties whose alliance is based on a net refusal to heed the Israeli Supreme Court and a pact to instil a theocratic regime where there has been, since the state’s creation in 1948, a democracy. Both these goals are to be achieved by changing the law, giving parliament (the Israeli knesset) the right to dictate the terms of justice to the courts of justice. It is a situation the philosopher Plato had staged at the start of his Republic, back in the 4th century BC.

The state of Israel is on the brink of deliquescence. A corrupt multi-indicted prime minister has handed the reins of government to extremist (read: blood-thirsty) right-wing (read: populist imperialist) religious (read: obscurantist) coalition parties whose alliance is based on a net refusal to heed the Israeli Supreme Court and a pact to instil a theocratic regime where there has been, since the state’s creation in 1948, a democracy. Both these goals are to be achieved by changing the law, giving parliament (the Israeli knesset) the right to dictate the terms of justice to the courts of justice. It is a situation the philosopher Plato had staged at the start of his Republic, back in the 4th century BC.

“What is justice?”, ask the half dozen citizens of then democratic Athens whom Plato reassembles at the start of his fictitious dialogue, written some sixty years after democracy fell in Athens and Socrates had been put to death. Amongst the cast of real-live people from then (Socrates of course, Plato’s own brothers and other public figures of the time), a Peter Thiel figure, called Thrasymachus (smart, amoral, with self-confidence oozing from his fingernails) hijacks the discussion to state his seemingly irrefutable answer: “justice is what the strongest party says it is”. The whole of Plato’s Republic (nine out of its ten books) is an attempt to counter this statement, a challenge directed at Socrates, tasked with proving that it is not so; that justice is in fact independent of any parties or any single individual. It turns out to be a more complicated challenge to meet than it would have seemed at first blush. For justice to be accepted as independent from the people in power, allowing for the possibility that justice even be detrimental to them, a whole rethink of society is required. The place where this rebalanced society lives is the republic, a place which…does not exist.

Plato’s republic is a utopia. But does it mean that the view it is meant to thwart, is reality? If Plato’s idealism has always been a utopian marker, out there on the horizon, the foundations of modern democracies have been built on centuries of discussions spawned by Plato’s work (in which democracy is presented only as the better of the worst of regimes). A standing block of democracy inherited from Plato, is the basic idea of a division of powers between the law-makers and the judges. That is to say that utopias can leave a mark on reality. And that is perhaps what makes them so cruel: they are eternal teases. If only you made another little effort, you could reach them. Israel, the democratic state of Israel, is, from its inception, torn between utopia and choosing the better of the worst; perhaps opting more often than not, for the worst of the worst.

What Plato does not discuss is why we should desire to live in the republic. For him it is obvious: having proved that in it, everyone is better off, it follows that it is the most desirable. It is a matter of common-sense logic. If you know it is good why would you not want it? Utopia exerts a deep attraction on us.  But the reason probably is that it is not for consumption. The only reason you could want to live in utopia is because you never will. But Israel is just such an impossible bird: a utopia yearned for and a lived-in reality.

But the reason probably is that it is not for consumption. The only reason you could want to live in utopia is because you never will. But Israel is just such an impossible bird: a utopia yearned for and a lived-in reality.

The state of Israel was born out of a double necessity: messianic on the one side, and desperate on the other. If the first, spiritual, impulse determined the place – the supposed ‘promised land’ of the Old Testament, the land that God promised an Egyptian named Moses in a conversation sealed with a divine kiss[1], pointing to the strip of land north of Egypt – the pragmatics allowed for the concrete establishment of an independent state in 1948. The pragmatics are well-known: a desperate geo-political situation in which thousands of Jewish people found themselves stranded with nowhere to go after a war, in which a genocide of six million Jews left survivors and refugees bereft of home and homeland. The infamous case of Exodus 1947, a ship transporting four and a half thousand Jews, sent traipsing for months on end to and fro the Mediterranean from France to Palestine and back, arriving even to the North Sea only to be sent back to Palestine, is exemplary (and certainly not unique) of the desperate situation which finally drove the United Nations to adopt the Resolution that recognised the state of Israel as located in a part of then Palestine (a territory under British rule).

A constant in the history of the yet non-existent Israel of the early twentieth century was its mirage quality, its proximity to a dream. When Theodor Herzel (1860-1904), one of the founding ideators of a Jewish state, declared in his famous visionary speech at the Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897: “if you want it, it shall not be a dream”, he both acknowledged the dream quality of the idea, and anticipated the turn-around that the reality of a Jewish state would do to utopia. What is no longer a dream, is a reality, a place where choices between the better of the worst are made. Herzel had founded the Zionist Organisation not so much out of a messianic drive, as a plea for the right to live. A fully assimilated, German cultured journalist and lawyer, he came to the conclusion that a state for the Jews was a necessity in the face of the implacable and un-eradicable antisemitism he was surrounded by, whether in the student union at his alma mater, the University of Vienna, or in the years of the Dreyfus affair in France where he was a correspondent for a Viennese paper. The Zionists of the first half of the twentieth century fuelled their dream of a utopia, (where people would not be discriminated against on the basis of a supposed racial origin), on the hope of its realisation. The certainty that such a utopia can be realised is, however, a contradiction in terms, a utopia cannot exist. It is a contradiction which is familiar not so much from politics as from poetry.

In a prose poem published posthumously in 1869, Charles Baudelaire picks up a theme as old as time – or at least as old Cain (a Baudelairean anti-hero we shall return to) – that the grass is always greener on the other side. He says it better and with a twist: “life is a hospital in which every patient is possessed by the desire to change beds”[2]. It is not only that next door always seems better to us, but that what we fantasise to exchange our own sorry lot for, is in fact as sorry and miserable as our own.

What lies at the heart of this fantasy? Two bleak – splenetic – ideas: first that we think nothing can be worse than our own lot, (whether rightly or wrongly), second, that anywhere else than where we are must, for that reason, be better. We therefore wish to exchange our lot for the other. Baudelaire’s premisses have a generalising scope: we are all infected by these thoughts and being infected, we are all sick, mad – we belong in an asylum. In fact, that is where we all are: “life is a hospital”.

There should be a consoling or even reassuring backdrop to this apparent truism. It is written in the ink of a centuries-old tragic-realism. The 17th century moralists elevated it to the level of a metaphysics of emptiness. We relentlessly escape from the glaring void of our existence through what Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) theorised as benumbing entertainment (‘divertissement’). In Baudelaire’s day, the truism had been moulded by Arthur Schopenhauer into a philosophy of the continuous desiderative pendulum, inevitably tipping the balance for a time towards desire, then to boredom with desire satisfied, and then towards desire once more. The very image of the hospital that Baudelaire evokes, is likely taken from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s The Conduct of Life. Less depressingly than Schopenhauer, Emerson’s version is more pragmatic and deterministic: “Like sick men in hospitals, we change only from bed to bed, from one folly to another.”[3] The philosophers thus, with variations, agree to diagnose a congenital yearning we all share, an insane conviction that next door must be better, identifying in this form of insanity, the very motor of our actions. Being all mad, this kind of madness has the stamp of normative sanity.

But with Baudelaire, the truism is subverted: if the yearning to change state is a familiar theme in his poetry (prose and verse), it is a yearning that is always despairingly directed to a place that cannot exist. Where normal madness as it were, is to yearn for a place, other than your own, that you can reach, see and touch – the place next door – motivated by greed, envy and strategic resources, the abnormal madness is to yearn for the place that does not exist; the yearning for utopia, the yearning to leave the hospital altogether. It is the one aspect Plato had neglected in his analysis: who can truly desire to realise a utopia, in full awareness of its perfections, for its own sake?! Someone convinced that a perfect place exists and at the same time that it is impossible to reach. For whilst rationality will lead you to the obviousness of the republic, rationality alone cannot suffice to take you through all the painful steps to reach it.

Là tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté

Luxe, calme et volupté

There, all is but order and beauty,

Splendor, calmness and velvety rapture[4]

But this ‘there’ is nowhere. And here lies the Baudelairean spleen: the loss of hope that extends beyond melancholy or depression, for a place that must exist. A spleen darkened by the anxiety that this other, better place, (the ‘there’), shall never be found. And all the while, the poet is burnt up inside by the desire to find it, so much so that this desire for a utopia dominates all other considerations about life. The Baudelairean spleen reaches thus further still than the sublimity of his poetry, to constitute a philosophy of its own: a philosophy for the accursed.

There are two genealogies of the accursed that spin out of post-Romantic French poetry of the second half of the 19th century: the Baudelairean and the Verlainean. If it is Paul Verlaine who, with his 1884-1888 essays on The Cursed Poets (Les Poètes Maudits) crystalises the curse in terms of singular aspirations to an absolute by poets who in their lives are derided and marginalised, destined to die young or miserable or both (referring to himself, but also Arthur Rimbaud, Tristan Crobière, or Marcelline Desbordes-Valmore), the Baudelairean curse is different. Sure, there is the misery and the marginalisation, but the curse, with Baudelaire, is the curse to forever be on the move. His is the curse of Cain, where Verlaine’s is the curse of Saturn. Where Saturnian melancholy is obnubilated by the absolute: absolute poetry, absolute love, absolute sacrifice, the curse of Cain has no end: “will your torment/ever have an end?”, “burning heart/ beware of such huge appetites”, “on the roads/ dragging behind you your family in dire straits.”[5].

Somewhere between romanticism and decadence – between Alfred de Vigny and Paul Verlaine – is Baudelaire’s singular account of the cursed poet, who belongs nowhere and yet keeps on yearning for an elsewhere, an anywhere but here. And that is where the prose poem we began with, in the hospital with our insane swapping of beds, leads to. It is a poem which begins, as we noted, with a general diagnosis backed, implicitly, by the philosophers. It then turns into a discussion between the poet and his soul, in the wake of a long tradition which stems, not from philosophy – not Descartes who distinguished the I from its body – but from François Villon, the 15th century poet who wrote a poem called ‘A debate between the heart and the body’, and in which he sets down the first footprints of the curse of Cain.

Villon’s heart claims allegiance to Saturn, the planet of poets: “my misfortune, is when Saturn gave me my burden to bear”, but his body states, against the pity-pleading heart, that “It is necessary to live (…) to read – what? [says the heart] – to read without ever stopping, to gain knowledge/To stay away from the madmen…”[6]. It is the body of the poet that subdues the heart and impels the poet to go on living, however cursed and miserable he might feel. In particular, it is the body that drives the heart to go beyond its natural (Saturnian) tendency to lament melancholically its own sad lot. No more. The heart must find new knowledge so as to avoid unhappiness[7].

Baudelaire continues the same centuries-long interrogation of the heart, now at a further stage of its acquisition of knowledge. Baudelaire asks his “soul” (“mon âme”) where – in the big wide world – it wants to live, now that it knows everywhere and everything – (remember the “huge appetites” of the “race of Cain”). The whole world parades in front of our eyes: Lisbon, Holland, Indonesia, south America, the Baltic. But mon âme keeps silent, until a final internal explosion gives the soul a voice to cry out: “Anywhere! Anywhere! As long as it is out of this world!”.

Maximal spleen, maximal outcry of a still committed search for a utopia that knowledge and experience have now confirmed is impossible to reach on this earth. Where else to go, when go we must? “It is necessary to go on living” said the body to the heart.

The curse of Cain suffuses the poetry of the Hebrew-language poetess of the early twentieth century, Rachel, known as she is by her first name only.  Ukrainian-born, Rachel Blaustein, (1890-1931) wrote poetry first in Russian and then in her newly acquired Hebrew, a resurrected language learnt in Palestine where she emigrated in 1909. Her poems – many of which have been set to music – tell of the mirage of utopia. The certainty of the existence of the desired ‘there’: “there, there are the mountains of Golan, stretch your hand, and touch them”[8], and at the same time the impossibility of reaching them and the doubts such an impossibility cast on the existence of that place. Rachel suffered from tuberculosis, she lived and eventually died at age forty not only in great physical suffering but alone and in poverty – all the right qualities for a cursed poet. But far beyond the individual circumstances of her life, her poetry encapsulates the schizophrenic foundations of the idea of Israel.

Ukrainian-born, Rachel Blaustein, (1890-1931) wrote poetry first in Russian and then in her newly acquired Hebrew, a resurrected language learnt in Palestine where she emigrated in 1909. Her poems – many of which have been set to music – tell of the mirage of utopia. The certainty of the existence of the desired ‘there’: “there, there are the mountains of Golan, stretch your hand, and touch them”[8], and at the same time the impossibility of reaching them and the doubts such an impossibility cast on the existence of that place. Rachel suffered from tuberculosis, she lived and eventually died at age forty not only in great physical suffering but alone and in poverty – all the right qualities for a cursed poet. But far beyond the individual circumstances of her life, her poetry encapsulates the schizophrenic foundations of the idea of Israel.

“And perhaps, none of these things ever happened,

Perhaps, I never rose with the dawn,

To work in the field, never felt the sweat on my brow?

(…)

My Kineret,

Did you exist, or was it all a dream?”[9]

Now that all the worst choices have been made in Israel, seventy five years after the utopia was given a concrete realisation, the only consolation would be that it has all been a dream – gone sour, but still, just a dream. Only that for Rachel, who died almost twenty years before Israel became a political entity, the possibility of realising the dream was always ahead, somewhere on the horizon line. She did not suffer from nostalgia, but the opposite, sick not to return but to arrive. That is Baudelairean spleen, the distress of having to go on.

But what of now, when the dream is definitely behind us? All there is room for is the suffocated voice of the splenetic soul: ‘Anywhere out of the world’. Israel is not the place where a utopia can arise. But where can it? The answer is not blowing in the wind, but percolating from a hospitalised spleen.

***

[1] From the Deuteronomy 34:5: “So Moses, the servant of the Eternal, died there, in the land of Moab, by the touch of the mouth of the Eternal.”

[2] Ch. Baudelaire, ‘Any where out of the world’ (title in English in the original), poem 48 in Le Spleen de Paris, Petits Poemes en Prose (1869).

[3] R.W. Emerson, The Conduct of Life, in section ix. ‘Illusions’.

[4] Ch. Baudelaire, ‘Invitation au Voyage’ in The Flowers of Evil (1861) (my translation throughout).

[5] Extracts from ‘Abel et Caïn’ in Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil.

[6] F.Villon ‘Le Débat du Coeur et du Corps de Villon’ in ‘Poésies Diverses’, collected in F.Villon, Poésies, Gallimard, 1973.

[7] From ‘Le Débat du Coeur et du Corps de Villon’ : ‘N’attends pas tant que tourne à déplaisance’.

[8] Rachel, ‘Kineret’ written in 1923 : « שָׁם הָרֵי גוֹלָן, הוֹשֵׁט הַיָּד וְגַע בָּם » in רחל: שירים מכתבים רשימות קורות חייה (Rachel: Poems, Letters and Essays) edited by U. Milstein, Tel-Aviv: 1985 (my translation).

[9] Rachel, ‘Perhaps these things never were..’ ibidem, put to music and sun here by Arik Einstein.