by Dwight Furrow

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

According to existentialism, as the role of God in modern life receded to be replaced by a secular, scientifically-informed view of reality, the resulting loss of a transcendent moral framework has left us bereft of moral guidance leading to anxiety and anguish. The smallness of human concerns in a vast, uncaring universe engenders a sense that life is inherently meaningless and absurd. There seems to be no ultimate purpose in life. Thus, our individual intentions are without foundation.

As Camus wrote:

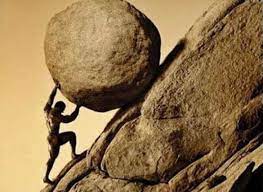

The absurd is born in this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world. (From the Myth of Sisyphus)

And so, for Camus, human suffering is like the toils of Sisyphus condemned to endlessly roll the boulder up the mountain only to have it roll down again—life is a series of meaningless tasks and then you die.

Sartre, for his part, argued that the demise of a theistic world view means we must now confront the incontrovertible fact of human freedom—no state of affairs can cause us to act in one way rather than another. Furthermore, there are no values that have a claim on us prior to our choosing them. Instead, at each moment, we make a choice about the significance of facts and our relation to them. If life is to be meaningful, we must invent that meaning for ourselves. We are thus “condemned” to be free and must take full responsibility for our actions and the meaning we attribute to them.

But in the absence of a moral framework, there is no way to know in advance whether a proposed action is right or wrong, good or bad. We must make choices that shape our future without knowing their consequences and that leaves us awash in anguish and despair. Sartre managed to build the entire plot of his novella Nausea around a character whose feelings of disgust with ordinary objects and the people he encounters reveal the fundamental contingency of all existence—nothing has a reason to exist. Everything is just there by accident. The suggestion is that all of us would feel such absolute disgust with life if we were just a bit more aware.

Heidegger’s main existential worry was that in the absence of a firm belief in an afterlife we face our mortality with feelings of dread and anxiety, feelings that can come over us when slumped in front of the TV, toiling in our work cubicles, or having a conversation at dinner. These feelings of dread and anxiety cause our world to collapse and cannot be alleviated but only lived with authentically by resolutely and steadfastly choosing the individual destiny our history makes available.

Anxiety, dread, meaninglessness, and forlornness in the face of a mute, incomprehensible universe–I don’t deny that people have these experiences. Existentialism found a large audience and profoundly influenced culture. Their evocation of the absurd resonated with many. But I doubt that most people worry about absent foundations or the irrationality of the universe. Neither are they deluded or living in bad faith in dismissing such thoughts. For every former believer bereaving an absent God there is a committed atheist joyfully flourishing. For every Bohemian huddled in a café musing over Cioran or Waiting for Godot, there are multitudes accepting suffering as part of life while celebrating their impermanent victories with a glass of wine and a gathering of friends and family. The meaning of life isn’t in question. The problem of staying alive and minimizing suffering is a practical matter of skillfully arranging one’s affairs and hoping for good luck.

Most human suffering is from pain or poor heath, poverty, war, violence or the threat of violence, prejudice, the failure of one’s projects, and loneliness. We sometimes find it impossible to cultivate relationships that satisfy us, and even when we succeed those relationships can go bad. We may find the people we work with are jerks or our family members hateful and not to be trusted. We make mistakes for which we feel guilty. We are beset by worry about the people we love. Some of us achieve everything we want yet still are unsatisfied. Others have difficulty shaking off traumatic events in the past that haunt them throughout their lives.

In other words, we are harmed by the particular circumstances in which we live, the people with whom we associate, our own weaknesses and ignorance, and the social, political, and economic structures that inhibit flourishing. However, if you find your job meaningless and the people around you hateful, there is no straightforward connection between those conditions and a disenchanted universe. For some people, getting out of those circumstances is like Sisyphus pushing the stone up a hill. But for every story of personal failure there are stories of personal success at solving problems in living. Of course, whatever victories we achieve are temporary and we will have to fight those battles again and again. And some problems are intractable. There is often nothing we can do about illness or pain. Victims of prejudice, poverty, or violence are victims of systemic problems outside their control. However, life is not made absurd by the fact that some problems are difficult or unsolvable.

This is not to say that human beings don’t suffer from a loss of meaning. We surely do, but its source is in the degraded ecology of an individual’s life. If we find meaning in a relationship and it is collapsing, we might suffer a loss of meaning. If your choice of career is no longer satisfying, then a loss of meaning or purpose might ensue. If your life doesn’t live up to your expectations, life will seem meaningless. However, putting aside cases of clinical depression, loss of meaning isn’t generally global or metaphysical. It attaches to specific actions or circumstances and our ability to make them intelligible, a misalignment between one’s actions and the meanings they are supposed to have. As to the slaughter-bench of history, it has received a technological upgrade in recent decades but the motives haven’t changed. Greed and lust for power are mundane, not metaphysical.

The existentialists were right that human life is saturated with contingency, but it was so long before Nietzsche announced the death of God. Existentialists are to be commended for reversing the tendency of our philosophical traditions to ignore the difficulties of life as if abstract logical certainties could replace the certainties of faith. But the problem is in the longing for certainty, not its absence. If contingencies and precarities make life absurd it’s because we have an expectation that life should not be contingent. That is an absurdity. We are after all biological creatures cursed with self-awareness and conscious of our uncertain future. “One moment alive, the next moment gone” doesn’t make life absurd. It makes it precious.

Happily, Camus and Nietzsche end up in the right place—viewing the struggle for life as itself meaningful despite its ultimate failure. But the detour through nihilism seems unnecessary, a product not of a trenchant analysis of human existence but of misplaced hope in a redemptive future.

For more on philosophy as a way of life visit Philosophy: A Way of Life