Tom McLeish at Marginalia:

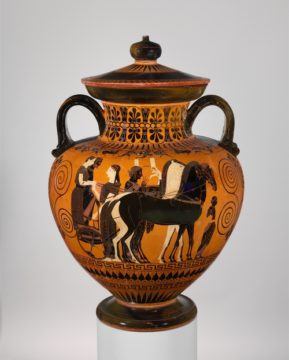

There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking.

There are distinct signs that the poet John Keats’ Grecian Urn has found its voice again. This is a surprise. The final Delphic utterance of the decorated vessel in his poem Ode to a Grecian Urn runs: “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Though well-known as verse, it has long been relegated to romantic wishful thinking.

The dominant, highly dualistic discussion of beauty and truth over the last century, and of aesthetics more generally, has long stifled the wistful notion that beautiful ideas are more likely to be true than ugly ones. Furthermore, multiple voices in late modern philosophy adopt the equally dualistic assurance that the objective (truth) and subjective (beauty) simply don’t mix, that they support no connection, enjoy no conversation. Yet a recently-published and extensive survey of over 20,000 scientists in the US, India, Italy and the UK, The Role of Aesthetics in Science, by Brandon Vaidyanathan and Christopher Jacobi, found that only 34% of scientists disagreed with the statement declaring “mathematical beauty is a good indicator of scientific truth.” A very large majority also found that the objects of their scientific investigations were aesthetically beautiful.

Here, I want to explore the reasons for the apparent failure to suffocate the Urn’s continuing voice in our own time. Anticipating that this will require some philosophy as well as the testimony of science itself, the continually conflictual conversations between beauty and truth will require listening to the arts, as well as the sciences. Surprisingly perhaps, the road to resolution leads through theology.

More here.