The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant

The Fate of the Animals: On Horses, the Apocalypse, and Painting as Prophesy (Three Paintings Trilogy), by Morgan Meis, Slant

Review by Leanne Ogasawara

- The discovery of a book of letters written by a soldier and artist to his wife during World War I, and the recognition of this book of letters drives us into a consideration of the Great War, which was a kind of Apocalypse.

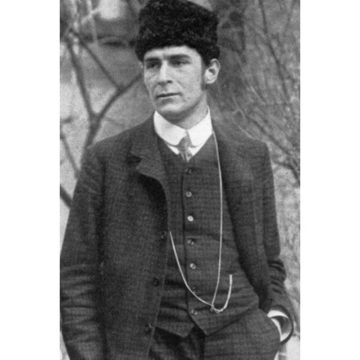

In 2011, philosopher and art critic Morgan Meis is wandering the halls of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. A show on German Expressionism is on, and Meis finds himself transfixed by a certain picture. It is Franz Marc’s 1913 oil, The World Cow. The languid rust-colored creature in the painting calls to mind a cow seen in real life. Recognizing those eyes, Meis recalls its patient stare. Wasn’t there perhaps a hint of rebuke in the cow’s eyes?

This cow becomes the moment of possession. Or perhaps it was more like the first beckoning; for a year or so later Meis stumbles on a book of collected letters that the German painter wrote to his wife whilst a soldier in the Great War. It would be in the war where Franz Marc would lose his life, his skull shattered by a bullet.

Meis is hooked.

Meis’s next stop is Switzerland, where he and his dear friend Abbas Raza—to whom the book is dedicated– stand before Franz Marc’s monumental 1913 The Fate of the Animals, in the Kunstmuseum, Basel. At first glance, he thinks it is a work of early abstract art. With its strong slashes of primary colors, the immediate impression is one of violence. Looking closer, however, the animals come into focus. There is a bluish deer in the lower center, appearing in grave distress. Is the deer being sacrificed? And if so, to what purpose, he wonders. Other animals—including boars and horses—can be just made out among the shafts of color. Is this the end of the world?

The Fate of the Animals is the second volume in what is a planned trilogy. Three books, one per painting.

As I mentioned in a review of the first volume, The Drunken Silenus: On Gods, Goats, and the Cracks in Reality, Meis is on a voyage of discovery in this series. Setting out to develop a new way to write about art, his project is informed by passionate looking.

I first noticed Meis’ new way of looking in an essay he wrote on Georgia O’Keefe in Image Magazine, “From the Faraway Nearby.”

How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour.

I thought how in written Japanese, the difference between looking as seeing versus looking as a deep form of attending is always explicit, making use of different characters to write the word miru. To see is miru 見るand to contemplate with one’s eyes–or to intentionally look at something is miru観る.The second kanji character is used as a compound in the term “appreciate” 観賞. In tea ceremony, practitioners learn to boil water and make tea. But the main activity is in learning how to appreciate and talk about beauty.

This deep looking and listening is essential to connoisseurship. And it seems to have become a lost art in today’s world. Whenever I read Meis, I feel transported back to a time when intellectuals had charming and erudite conversations about subjects like art, history, and music. Not only could they bedazzle at a cocktail party, but they could write about it too. Reading Meis, you feel yourself in the most engaging company.

This deep looking and listening is essential to connoisseurship. And it seems to have become a lost art in today’s world. Whenever I read Meis, I feel transported back to a time when intellectuals had charming and erudite conversations about subjects like art, history, and music. Not only could they bedazzle at a cocktail party, but they could write about it too. Reading Meis, you feel yourself in the most engaging company.

And so in this book, a man stands in front of you, telling you about this certain picture he likes. Well, it’s not that he genuinely likes it. More that he decided to look deeply at it. To spend time with it. To think long and hard about it.

Oh, and I should mention that the book is divided into chapters which have headings in the form of long sentences. These are code to unlock the book. And so below, we have chapter four:

- We delve deeper into Franz Marc and his gratitude for war and also explore his desire to paint even though, for most of his life, Franz Marc was a shitty painter. WE OUGHT TO LET this thought sink in.

A shitty painter? As a German Expressionist artist, Marc is often grouped with Wassily Kandinsky and August Macke, who were his co-founders of Der Blaue Reiter, the Blue Rider almanac. It was Kandinsky who first created what came to become the symbol of the movement, a man on a blue horse. But then again, it was Marc who became more firmly associated with pictures of blue horses. As Meis tells the story, Marc was a painter of horses by 1910—and continued to draw horses, along with other animals right till his premature death in the war in 1916. Creating paintings in the style of the German Expressions, which favored bold primary colors and prioritized representing emotion over replicating reality.

But the sweet, joyfully romping cows of his earlier works are transformed into something more ominous as the shadow of World War I drew near. In fact, Marc painted The Fate of Animals less than a year before Archduke Francis Ferdinand was assassinated, in 1914. The painter would die two years later at the Battle of Verdun. He was only thirty-six.

Morgan Meis is one of my favorite writers. Not just that I appreciate his ideas, but I deeply admire his craftsmanship in writing beautiful sentences. In this book, I was struck by his vivid depictions of the bloody battle in which Marc lost his life. For those who don’t recall, the Battle of Verdun was fought between February and December 1916 on the Western Front in France. Some 700,000 men perished in what was a veritable blood bath. Literally, the blood of three-quarters of a million men drenched the rural French countryside where the campaign took place. Through a famous scene in a Stanley Kubrick film to a description of the murderous strategy employed by the German commander Georg Anton von Falkenhayn, Meis spares nothing in evoking what this blood-letting was like.

Morgan Meis is one of my favorite writers. Not just that I appreciate his ideas, but I deeply admire his craftsmanship in writing beautiful sentences. In this book, I was struck by his vivid depictions of the bloody battle in which Marc lost his life. For those who don’t recall, the Battle of Verdun was fought between February and December 1916 on the Western Front in France. Some 700,000 men perished in what was a veritable blood bath. Literally, the blood of three-quarters of a million men drenched the rural French countryside where the campaign took place. Through a famous scene in a Stanley Kubrick film to a description of the murderous strategy employed by the German commander Georg Anton von Falkenhayn, Meis spares nothing in evoking what this blood-letting was like.

Was it any wonder that Marc’s paintings turned dark? And yet, according to Meis, who was still reading the letters Marc sent home to his wife Maria, Marc did not consider the war to be evil.

At this point, I was expecting Meis to turn to Nietzsche and to Dostoevsky. To depict horses as symbols of the virtue of the untrammeled human spirit has a long history in European letters and art. If the truth of our human lives is being dulled by the comforts of “civilization.” and if we are therefore asleep to the world, then war is a kind of wakeup call. Meis, however takes a different—and much more fascinating turn– by bringing in Heidegger and DH Lawrence.

- A painter discovers color, really discovers it, really embraces the power and mystery of color, and also, perhaps by extension, discovers the power of fate, of destiny, which is a dangerous power indeed. Heidegger, the Nazi philosopher, makes a brief appearance.

According to Meis, there was a point in Marc’s life when his paintings– which had previously been lacking in purpose or direction –suddenly became revelatory.

Meis is crucially reminding us that “revelation” and “apocalypse” are different translations of the same word. They mean the same thing.

Meis is crucially reminding us that “revelation” and “apocalypse” are different translations of the same word. They mean the same thing.

Like Franz Marc, philosopher Martin Heidegger was also a soldier during the Great War—albeit one who sat at a desk. Marc, in the months before he perished, wrote to his wife Maria of fate. Meis, then, links this to Heidegger’s notion of fate or destiny from Being in Time. Schicksal, according to Heidegger, is the “state of being sent.” It is our human thrownness, and following on the footsteps of Nietzsche, Heidegger felt the authentic life was somehow taken up by those people who accept –or even love—their fate. Amor fati is not just an acceptance of one’s fate but is a love of it. Indeed, it is an active choosing of it.

Marc accepts the fate of the war with all its artistic and moral possibilities. And this deepening spiritual and moral questioning led to the burgeoning genius of Marc’s later works, especially the Fate of Animals. Note the word “fate.”

- We’re in the midst of a battle now, between D.H. Lawrence and Franz Marc, around the question of what it means truly to be alive. Who will win? It comes down, as it so often does when you get into it with Lawrence, to the question of fucking and how to do it right.

I was still waiting for Nietzsche to show up in these pages, but Meis without warning turns to DH Lawrence. I really did not see that one coming. But then again, as Meis explains, it wasn’t that Marc in his paintings wanted to strip off his clothes and in some kind of Nietzschean moment embrace the spiritual magnetism and virtue of horses– though that was the message of DH Lawrence, who felt that human beings should embrace their unbridled physicality. Because, no, we are not encapsulated minds in bodies prone to be our own worst enemies. Humankind had become so alienated to our natural state that we had all become something of the likes of Ivan Karamazov. Loving humanity but hating our neighbors, we have lost the strength and spiritual truth of our human physicality.

Hence, pictures of animals?

But according to Meis, this is as far as the comparison goes; since Marc was interested in going beyond the merely natural state of man to penetrate something of the truth of our human condition. Franz Marc had studied Christian theology deeply in his youth, and so Meis brings in the Christ of the Gospel stories. Jesus stepped into history to heal human beings by first healing their bodies. Making the blind see and the infirm stand. This was, however, never an end in itself; for it was through the body that the spiritual truth of our human condition can be uncovered.

But according to Meis, this is as far as the comparison goes; since Marc was interested in going beyond the merely natural state of man to penetrate something of the truth of our human condition. Franz Marc had studied Christian theology deeply in his youth, and so Meis brings in the Christ of the Gospel stories. Jesus stepped into history to heal human beings by first healing their bodies. Making the blind see and the infirm stand. This was, however, never an end in itself; for it was through the body that the spiritual truth of our human condition can be uncovered.

And here we are getting to the heart of the Fate of the Animals.

Meis notes that the painting is today found in Basel, a city known for its commitment to the accumulation of money. Franz Marc probably would have hated to know his masterpiece could now be seen in the city which so totally represented the “European comfortableness” that the painter deplored as a kind of death more horrible that physical annihilation, since it was a death of the spirit. Meis writes:

What Franz Marc desperately hoped for, to be perfectly honest, was that the Great War would destroy everything in the European soul that led, in actual fact, in actual history, to the Basel of today, to the rich and content and self-satisfied cities of Switzerland in the early twenty-first century. Franz Marc was disgusted by that sort of wealth and comfort, and he wanted it all to be destroyed. We can’t sugarcoat this thought or turn away from it. Franz Marc loved and admired the World War, a war that killed millions and destroyed his own civilization…

- The drama of Paul Klee and The Fate of the Animals becomes even deeper and more surprising, and we begin to realize that the painting The Fate of the Animals is itself an object of fate, with perhaps also a little dash of grace.

Standing in front of the monumental painting in Basel, Meis confronts the picture. At first glance there is disharmony and confusion. It is hard to understand what is going on. It takes time to allow the picture to reveal itself so to get an idea—even if just a hint, a taste, a glimmer—of the spiritual scene beneath the surface. Heidegger wrote at length about the way certain works of art “work” to uncover a different understanding of being. They can serve almost as portals to a different world. This is a prophetic vision that is not necessarily oriented toward the future—but rather is a kind of passionate seeing that opens something in the here and now. A different view of the world, or a different spiritual understanding, that is always present, if only we open our eyes.

Looking at the picture, we see a maelstrom. On the back, Marc had scribbled a verse from the ancient Vedas: “And all being is flaming sorrow.”

Sorrow can be an awakening.

Shortly after Marc’s death, a warehouse fire destroys half the painting. Marc’s friend artist Paul Klee steps into the life of the painting to repair it, choosing to not reproduce the original vibrant colors, leaving them more brown in hue, perhaps to evoke the fire. Or perhaps to make sure no one mistakes that he was not daring to recreate the original. Knowing his friend’s work intimately, Klee had years before suggested a different possibility for the picture: The trees show their rings, the animals their veins.

Is this the religious truth of the world? The apocalypse as revelation of the Vedas, of Norse mythology and the god Odin—and not to mention the God of the Tetragrammaton?

Just like in the first volume of the trilogy, we find, in standing alongside Meis as he confronts this monumental work of art—that examining the particular can reveal deeper truths.

For more:

A World of Tears: my review of his first book, in Dublin Review of Books

Ekphrastic Writing Responses: Franz Marc (See Brooks Riley’s response halfway down the page)

The Eye: An Insider’s Memoir of Masterpieces, Money, and the Magnetism of Art

by Philippe Costamagna