by Rebecca Baumgartner

In T.H. White’s masterpiece The Once and Future King, Merlyn’s recommendation for “see[ing] the world around you devastated by evil lunatics” is to learn something:

“There is only one thing for it then – to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting.”

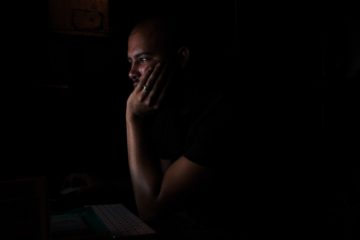

This summer, as I’ve watched my own country being devastated by evil lunatics, I’ve tried to take this advice to heart. Under Merlyn’s tutelage, the future King Arthur learned about his world by taking the form of various animals and seeing how they lived. We have to make do with a different form of sorcery – one that, rather than educating us about others, merely shows us a reflection of ourselves fractally repeated; one that keeps us sad and angry and has proven to be far less helpful in dealing with evil lunatics than one would hope: the internet.

When the Supreme Court released its now-infamous round of rulings towards the end of June – in a whirlwind week that felt like the answer to the question, “What if America were a monarchy?” – I obviously turned to the internet to find out what I could do.

But, as I quickly discovered, it’s hard to formulate a series of Google search terms that could possibly lead to anything helpful right now. The fact that I tried to do so anyway is a telling demonstration of how our capacity for action is mediated and diluted by the internet.

I googled “how to take action against the Supreme Court decisions” and “what can the average person do to fight the Supreme Court?” Although a few pieces came tantalizingly close (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tweeted a list of things Congress can do, which is helpful if you happen to be one of the 0.00016% of the U.S. population that’s in Congress), for the most part they ended up leading to a limited set of unsatisfying options: donate money, vote, and inform yourself. Having done the first, and planning to do the second in a few months, all that’s left is staying informed. Which increasingly means: click here and keep reading (preferably forever) about how terrible everything is. If any given article suggested taking action of any kind, it usually referred you back to donating, voting, and informing yourself, in an infinite loop of powerlessness.

It almost goes without saying that most websites are more concerned with keeping us reading than in equipping us to act. As far as the internet is concerned, keeping us informed and upset is the only goal, and our ignorance and capacity for anger is a highly renewable resource. We know more details about each catastrophe than ever before, while at the same time being less motivated to do anything about them.

As Jia Tolentino says in her 2019 essay “The I in the Internet,” the internet provides “an unlimited supply of terrible information” while serving as a “shunt diverting our energy away from action, leaving the real-world sphere to the people who already control it.” The internet is a mirror that shows us how powerless we are, and we can’t look away.

The demand to “stay informed” creates and nurtures that feeling of helplessness. By now, it’s common knowledge that social media is exquisitely crafted to make people feel terrible, but it’s also being increasingly recognized that mainstream news media is just as bad. Even journalists are starting to avoid consuming the news these days, in a parallel to Silicon Valley executives not letting their own kids play with the addictive apps they’ve designed. In a recent opinion piece in The Washington Post, journalist Amanda Ripley describes feeling paralyzed into inaction once the news had “crept into every crevice of life”:

“It’s not like I was reading about yet another school shooting and then firing off an email to my member of Congress. No, I’d read too many stories about the dysfunction in Congress to think that would matter. All individual action felt pointless once I was done reading the news. Mostly, I was just marinating in despair.”

In imagining what a better kind of journalism might look like, Ripley points out that:

“Humans need a sense of agency. ‘Agency’ is not something most reporters think about, probably because, in their jobs, they have it. But feeling like you and your fellow humans can do something – even something small – is how we convert anger into action, frustration into invention. That self-efficacy is essential to any functioning democracy.”

Despite movements such as Solutions Journalism, we’re still not to a point where most news outlets give readers or listeners a sense of agency. Even the outlets discussing how to take action operate within a universe where simply reading about an action, or talking to others about it, carries almost the same moral weight as doing it. Over the recent 4th of July weekend, NPR ran one of their feel-good “let’s talk, friends” newsletters on how to raise the next generation to be good citizens in the face of the Supreme Court’s penchant for ruling by fiat (“You’re not alone in feeling emotionally charged,” they soothed us).

I interpreted this focus on the next generation as an implicit admission of defeat, but one that allows us to still feel good about ourselves as long as we talk to our kids about voting and not being racist. The profoundly exhausted grown-ups can’t or won’t solve this; our only hope lies with whatever energy and innocence remain in our pandemic-brutalized and academically under-equipped children. The most we adults can do now is continue doomscrolling under the guise of informing ourselves, hoping that the fleeting sense of control we get from voting in November is an antidote to the learned helplessness we all think is normal now.

It’s clearly time to go beyond being informed. But it’s simultaneously not obvious what we should do instead.

We like pat answers and simple actions that make us feel good, such as voting, donating money, donating blood, emailing representatives, reducing our use of plastic, putting flags in our yards, and crossing our fingers and hoping the ACLU is doing something – the kinds of things that Tolentino describes as “mainstream gestures of solidarity” that are “pure representation.” These gestures – which are not exactly empty, but certainly feel better out of all proportion to what they actually accomplish – also serve the interests of those in power who are reluctant, for whatever reason, to act.

Most of us are participating in democracy in the same way that a toddler “helps” you cook dinner (here, just stir this until you’ve reached the minimum level of engagement that would be satisfying to you, so you can say you helped). A brilliantly scathing piece in McSweeney’s makes this point brutally clear: “It makes sense you’d feel angry at what’s happening…As the people in power, we can tell you that the best way to solve a problem happening right now is us waiting for you to vote later.”

However, while it is certainly better to take some kind of action if we can, it would be wrong to assume that our problems are ones that individual citizens can, or should, fix. This mindset is essentially the conservative catechism of personal responsibility, which uses individual obligation as a smokescreen for pervasive structural deficiencies and governmental and corporate failure to address them.

The present moment, and our reactions to it, highlight the division between what a single person can or should do, and what our social institutions are obligated to do. The inspirational cliche “Be the change you wish to see in the world” may come from a place of hopefulness, but it participates in the larger project of misdirection in which we’re all supposed to accept that the groups with the most power and resources shouldn’t be burdened with making anything meaningfully better. When the institutions fail us, we’re supposed to double down on personal responsibility.

(The fact that people who consider themselves religious often hold this view is a degree of hypocrisy so profound that it’s just part of the scenery now; to quote the song “The Doomed” by A Perfect Circle, “The new beatitude: ‘Good luck, you’re on your own.’”)

Individuals having to carry the load dropped by institutions is not at all uncommon in American culture, of course: Just think of repeated exhortations to women that they could fix sexism if they simply had more confidence or learned how to negotiate better. Or that if we all used paper straws, we could counteract the damage done by the largest sources of environmental destruction in the world, which continue to evade accountability. Or that hospital staff should be expected to craft their own makeshift PPE during a pandemic, while the Trump administration issued hand-waving statements (“At some point this stuff goes away”), explicitly refusing to take ownership for something that required, by its very enormity, solutions from institutions rather than from individuals.

It’s not much of a stretch to predict that America’s fixation on the individual at every level of civic life will prove to be our undoing, when so many of the problems we need to solve require coordinated, organized action and major institutional change.

But so many of our institutions – such as Congress – are hobbled into near uselessness by ossified power, corporate lobbying, and conflicts of interest. In the absence of a political atmosphere that values finding common ground and getting things done, assigning individual people simple tasks that require minimal effort for maximal emotional reward – voting, recycling, putting up signs in your yard – is a way to keep people engaged and feel like they’re helping.

These civic gestures aren’t bad in themselves, but they can blunt our ability to recognize that the institutions and corporations charged with solving problems, creating opportunities, and protecting liberties are being let off the hook. Our mainstream gestures of political engagement are so often mere busy-work.

What’s the alternative? As a first step, we should recognize the fine line between informing ourselves and doomscrolling, and resist consuming more terrible information than we need to. It numbs us, overwhelms us, polarizes us, entrenches our biases, and diverts our energy away from taking action.

When we decide to go beyond merely being informed and decide to take action, we should avoid getting swept up in micro-virtues that make us feel good without really achieving anything. It’s difficult, of course, because the main place where we go to make ourselves feel good without achieving anything – the internet – is set up to reward the performance of these micro-virtues as a reflection of our personal worthiness. Needless to say, we should try to resist that.

Instead, our energies would be better spent taking more meaningful actions. That will look different for each person based on their situation and resources, but it’s likely to be something less emotionally satisfying and less self-congratulatory than the gestures we’re used to.

Furthermore, our engagement needs to be sustained and woven into the fabric of our lives, not just a patchwork of one-time actions performed in a crisis-driven burst of motivation. This less reactive form of engagement is kinder to our overstressed primate brains, less psychologically taxing, and ultimately more effective – there’s always going to be another crisis, and we need to play the long game.

At the same time, and perhaps most crucially, we should recognize that our individual contributions are only a starting point. The real change starts happening when we focus on holding our institutions accountable for fixing the devastation they allowed the evil lunatics to create.