by Rafaël Newman

The month of May begins and ends with festivals of rebirth—at least here in Zurich, where May Day, the “Revolutionary First of May,” is a statutory holiday, while Ascension, the commemoration of Jesus’s foundational transubstantiation, having been retained as a feast day by the local Protestant reformers, is routinely observed on the last Thursday of the month. May thus boasts, at its head and tail, the celebrations of redemptive narratives canonized by the master transformational discourses of the West, the Marxist and the Christian, with a new worker’s world arising from the ashes of the old at one end, and the materially murdered Messiah resurrected as a transcendent, immortal, spiritual force at the other, Hegel spinning in his grave between them. And then of course, right in the middle of this median month in the vernal quarter of the year, the season of rejuvenation par excellence, there falls the culmination of yet another chronicle of presumed redemption and rebirth, its roots intertwined with both of those master discourses, the revolutionary and the religious: the anniversary of the founding of the state of Israel on May 14, 1948—but that’s another story.

In the German-speaking world, as in many other parts of Europe, the coming of May is also traditionally associated with a pre-Christian, pre-Communist fertility rite, observed with dances, maypoles, and bonfires, rituals shot through with the theme of rebirth, whether spiritual, as in the commemoration of the coming of Christianity to the pagan German lands on Walpurgisnacht, or physical, with more or less explicit invitations to procreation.

A popular German folk song, “Alles neu macht der Mai” (May remakes the world anew), to a text by Hermann Adam von Kamp (1796-1867), celebrates the splendors of spring in the northern hemisphere in a naturalist-romantic style that never quite decides whether it is animist or monotheist: the singer’s spirit rejoices with all of creation (“May remakes the world anew / cheers the soul and sets it free”) as young and old alike recline on Mother Earth (“the mossy floor folds great and small / to its tender bosom close”). A pedagogue and children’s book author, von Kamp skilfully interweaves a pious reverence with the burgeoning sensuality of his charges. And as it happens, “Alles neu macht der Mai” shares a tune with another children’s song, “Hänschen Klein” (Little Hans), in which a young boy ventures out into the world, much to the distress of his mother, in a sort of second birth as an individual subject. (This conjunction feels of particular significance to me, since my own birthday also falls on the very middle day of the month of May—but that, too, is another story.)

In Switzerland generally, where the originally fierce and rebellious May Day has been rendered a quaint relic by the public-private partnership model, a tacit agreement to avoid labor disputes in the name of a lucrative social peace, and the exigencies of serving the world’s sub rosa banking needs while keeping a firm hand on the safe-haven franc in the interests of an all-important exporting industry, the month of May passes intentionally without event until its final weekend, when the post-Christian Swiss society relishes the opportunity afforded by a Thursday holiday to “make a bridge,” and enjoy four days off. The long weekend at Ascension, when the weather is growing mild enough to gather outdoors and when the mountain passes have traditionally become viable once again, is thus also a good time to stage an international event, such as the Solothurner Literaturtage (SLT). This year, the annual literary festival, held in the riverside town of Solothurn in northwestern Switzerland, is itself celebrating a sort of rebirth, having been constrained in 2021, by virological rather than by meteorological conditions, to an online version.

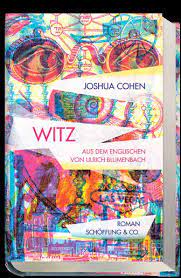

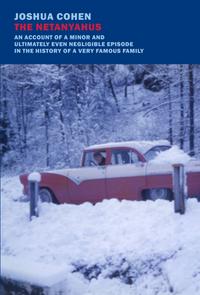

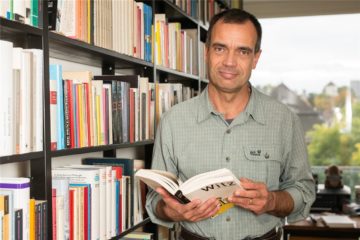

Among the many events planned for this year’s newly on-site SLT is a so-called Werkstattgespräch (“workshop dialogue”) on literary translation, devoted to the celebrated German translator Ulrich Blumenbach, renowned for his renderings—his rebirthings—of contemporary American fiction. I have been asked to moderate the discussion, in which Blumenbach will be joined by Sabine Baumann, his editor at Schöffling & Co. publishers in Frankfurt, because I was among the early reviewers of Blumenbach’s latest translation, that of Joshua Cohen’s monumental Witz: A Novel (Dalkey Archive, 2010; German version Schöffling & Co., 2022). Cohen, who has just won the Pulitzer for his most recent work, The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family (NYRB, 2021), in which he lampoons the early years of Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, will not be taking part in our discussion. Indeed, having been slated himself to read in Solothurn on Saturday and at the Literaturhaus Zürich on the following Monday, Cohen has now cancelled his European appearances altogether at the last minute: the American literary prize circuit oblige.

Among the many events planned for this year’s newly on-site SLT is a so-called Werkstattgespräch (“workshop dialogue”) on literary translation, devoted to the celebrated German translator Ulrich Blumenbach, renowned for his renderings—his rebirthings—of contemporary American fiction. I have been asked to moderate the discussion, in which Blumenbach will be joined by Sabine Baumann, his editor at Schöffling & Co. publishers in Frankfurt, because I was among the early reviewers of Blumenbach’s latest translation, that of Joshua Cohen’s monumental Witz: A Novel (Dalkey Archive, 2010; German version Schöffling & Co., 2022). Cohen, who has just won the Pulitzer for his most recent work, The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family (NYRB, 2021), in which he lampoons the early years of Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, will not be taking part in our discussion. Indeed, having been slated himself to read in Solothurn on Saturday and at the Literaturhaus Zürich on the following Monday, Cohen has now cancelled his European appearances altogether at the last minute: the American literary prize circuit oblige.

While it will be a shame not to see Cohen in the flesh, nor to hear him read from The Netanyahus, his ribald and savage campus novel-cum-reflection on Zionist revisionism, the author’s absence from our event, whether on the panel or in the audience, will make no difference, since what we will be discussing is not so much his work per se, as its resurrection in Blumenbach’s German. And we will do this, in part, by reviewing the material process of transformation in a comparison of the draft pages of Blumenbach’s translation, marked up by Baumann’s red ink, with his final clean versions.

While it will be a shame not to see Cohen in the flesh, nor to hear him read from The Netanyahus, his ribald and savage campus novel-cum-reflection on Zionist revisionism, the author’s absence from our event, whether on the panel or in the audience, will make no difference, since what we will be discussing is not so much his work per se, as its resurrection in Blumenbach’s German. And we will do this, in part, by reviewing the material process of transformation in a comparison of the draft pages of Blumenbach’s translation, marked up by Baumann’s red ink, with his final clean versions.

Furthermore, Witz itself, in its original English form, deals not only with a perverse sort of renaissance—that of the entire Jewish religion, following the mysterious death of all but one of the world’s Jews—but also with the “Jewish body” as guarantor of tribal authenticity and as prophylaxis against imputed antisemitism, even as the novel stages a fictional resurrection of the historical Holocaust, this time with the “Jews” as perpetrators and the unconverted “goyim” as victims, and thus uncomfortably evokes the charges of genocide leveled against the actual, “reborn” Israeli state, and laid, by racist extension, at the doorstep of non-Israeli Jews around the world.

Cohen is a prodigy who wrote the immense, linguistically innovative Witz when he was barely out of high school, partly as a world-weary, Europhile rebuke to the early-millennial revival of Jewish culture, spearheaded by Jerry Seinfeld, in a newly “cool” format. Cohen went on to work as a foreign correspondent for a variety of periodicals, reporting from the sites of commemoration of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe and becoming known as a journalist who was more interested in dead Jews than in their living descendants; and Witz, among other things, is a meditation on the destruction of the Jews of Europe that counters the yawning nothingness of the Shoah, not by naively celebrating Jewish life in the diaspora, but with an over-abundance of grotesque imagery, wordplay both Joycean and hackneyed, and self-propagating neo-mythologies. Next, while publishing a series of his own novels and essays, Cohen also served as ghostwriter of Edward Snowden’s memoir, Permanent Record, the testimony of a truthteller forced to absent himself from his own life. Now, in The Netanyahus, Cohen has taken on the controversial theory that the exterminationist aspect of the Nazi “final solution” was in fact given a trial run during the Reconquista, when the newly ascendant Catholic monarchy, in its campaign of “reconquest” of the Iberian Peninsula, moved to break the power of the regional nobility by insisting on the ineradicable biological “contamination” of their converted Jewish viziers. In Cohen’s latest novel, set in the early postwar period, this thesis, which would eventually be immersed in the stream of Zionist ideology if not taken up by the academic establishment, is presented in a series of lectures held in the aftermath of the Holocaust by a prominent survivor: another encounter between historical fact and literary discourse.

Cohen is a prodigy who wrote the immense, linguistically innovative Witz when he was barely out of high school, partly as a world-weary, Europhile rebuke to the early-millennial revival of Jewish culture, spearheaded by Jerry Seinfeld, in a newly “cool” format. Cohen went on to work as a foreign correspondent for a variety of periodicals, reporting from the sites of commemoration of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe and becoming known as a journalist who was more interested in dead Jews than in their living descendants; and Witz, among other things, is a meditation on the destruction of the Jews of Europe that counters the yawning nothingness of the Shoah, not by naively celebrating Jewish life in the diaspora, but with an over-abundance of grotesque imagery, wordplay both Joycean and hackneyed, and self-propagating neo-mythologies. Next, while publishing a series of his own novels and essays, Cohen also served as ghostwriter of Edward Snowden’s memoir, Permanent Record, the testimony of a truthteller forced to absent himself from his own life. Now, in The Netanyahus, Cohen has taken on the controversial theory that the exterminationist aspect of the Nazi “final solution” was in fact given a trial run during the Reconquista, when the newly ascendant Catholic monarchy, in its campaign of “reconquest” of the Iberian Peninsula, moved to break the power of the regional nobility by insisting on the ineradicable biological “contamination” of their converted Jewish viziers. In Cohen’s latest novel, set in the early postwar period, this thesis, which would eventually be immersed in the stream of Zionist ideology if not taken up by the academic establishment, is presented in a series of lectures held in the aftermath of the Holocaust by a prominent survivor: another encounter between historical fact and literary discourse.

In his work, Cohen has thus repeatedly evoked themes of presence and absence, of body and spirit, and of the persistence of speech and writing in the face of silence and death. And he has done so in a welter of languages, natural and synthetic, and with an extraordinarily broad palette of literary and cultural references. Blumenbach, who had proved his mettle as a translator of difficult post-modern texts with his German rendering of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996; Unendlicher Spaß, 2009), among other projects, has had to be even more inventive in translating Witz. Paradoxically, it is precisely because Cohen’s novel is so permeated by Yiddish, which despite its significant admixtures of Semitic, Slavic, and Romance vocabulary and syntax is essentially a German dialect akin to Swiss-German, that it is a challenge to translate it into German, where the likeness of certain Yiddish words to their German cognates—such as mensch or fayg—requires a veritably Shklovskian process of “defamiliarization” to mark them as strange.

In his work, Cohen has thus repeatedly evoked themes of presence and absence, of body and spirit, and of the persistence of speech and writing in the face of silence and death. And he has done so in a welter of languages, natural and synthetic, and with an extraordinarily broad palette of literary and cultural references. Blumenbach, who had proved his mettle as a translator of difficult post-modern texts with his German rendering of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996; Unendlicher Spaß, 2009), among other projects, has had to be even more inventive in translating Witz. Paradoxically, it is precisely because Cohen’s novel is so permeated by Yiddish, which despite its significant admixtures of Semitic, Slavic, and Romance vocabulary and syntax is essentially a German dialect akin to Swiss-German, that it is a challenge to translate it into German, where the likeness of certain Yiddish words to their German cognates—such as mensch or fayg—requires a veritably Shklovskian process of “defamiliarization” to mark them as strange.

But Blumenbach goes further—because Witz requires him to. He must devise whole new sequences of portmanteau neologisms, onomatopoetic syntheses, and complex, interlingual puns, all of which need to work as well (or as badly) in German as they do in English. For Cohen’s style is a major protagonist of his novel, mirroring and indeed performing the shocking transmogrifications, both physical and spiritual, that it depicts. And although Blumenbach himself has suggested that the language of Witz enacts the gradual disintegration of established, “civilized” norms and structures that characterized the actual Holocaust, even as it invents a second, “reborn” Holocaust of its own, it seems to me more apposite to propose that Cohen’s literary propagation stages an anarchic rebirth of the world—the world of language—that constitutes a rebuke to the nihilism of nationalist extermination.

And it is Blumenbach’s own remaking of that world that we will celebrate, in Solothurn, on the weekend of Ascension, with an examination of the revolutionary, red-inked pages of his translation, and their textual transformation and rebirth.