Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in The New Yorker:

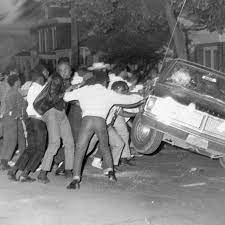

Since the declaration of Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s birthday as a federal holiday, our country has celebrated the civil-rights movement, valorizing its tactics of nonviolence as part of our national narrative of progress toward a more perfect union. Yet we rarely ask about the short life span of those tactics. By 1964, nonviolence seemed to have run its course, as Harlem and Philadelphia ignited in flames to protest police brutality, poverty, and exclusion, in what were denounced as riots. Even larger and more destructive uprisings followed, in Los Angeles and Detroit, and, after the assassination of King, in 1968, across the country: a fiery tumult that came to be seen as emblematic of Black urban violence and poverty. The violent turn in Black protest was condemned in its own time and continues to be lamented as a tragic retreat from the noble objectives and demeanor of the church-based Southern movement.

Since the declaration of Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s birthday as a federal holiday, our country has celebrated the civil-rights movement, valorizing its tactics of nonviolence as part of our national narrative of progress toward a more perfect union. Yet we rarely ask about the short life span of those tactics. By 1964, nonviolence seemed to have run its course, as Harlem and Philadelphia ignited in flames to protest police brutality, poverty, and exclusion, in what were denounced as riots. Even larger and more destructive uprisings followed, in Los Angeles and Detroit, and, after the assassination of King, in 1968, across the country: a fiery tumult that came to be seen as emblematic of Black urban violence and poverty. The violent turn in Black protest was condemned in its own time and continues to be lamented as a tragic retreat from the noble objectives and demeanor of the church-based Southern movement.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, in August, 2013, then President Barack Obama crystallized this historical rendering when he said, “And then, if we’re honest with ourselves, we’ll admit that, during the course of fifty years, there were times when some of us, claiming to push for change, lost our way. The anguish of assassinations set off self-defeating riots. Legitimate grievances against police brutality tipped into excuse-making for criminal behavior. Racial politics could cut both ways as the transformative message of unity and brotherhood was drowned out by the language of recrimination.” That, Obama said, “is how progress stalled. That’s how hope was diverted. It’s how our country remained divided.”

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)