Review of Fernando Castrillon and Thomas Marchevsky (eds) Coronavirus, Psychoanalysis, and Philosophy: Conversations on Pandemics, Politics, and Society (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021)

by Claire Chambers

In Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, the first-person narrator Saleem Sinai invites readers to imagine themselves in a large cinema, sitting at first in the back row, and gradually moving up, row by row, until your nose is almost pressed against the screen. Gradually the stars’ faces dissolve into dancing grain; tiny details assume grotesque proportions; the illusion dissolves or rather, it becomes clear that the illusion itself is reality.

In Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, the first-person narrator Saleem Sinai invites readers to imagine themselves in a large cinema, sitting at first in the back row, and gradually moving up, row by row, until your nose is almost pressed against the screen. Gradually the stars’ faces dissolve into dancing grain; tiny details assume grotesque proportions; the illusion dissolves or rather, it becomes clear that the illusion itself is reality.

This is a figurative way of talking about history’s distortions, or the difficulties of exploring contemporary events given the incomplete view afforded by a nearby vantage point.

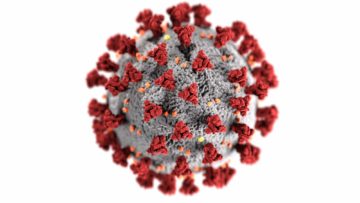

Such a confusing closeness to dramatic and discombobulating scenes is discussed in some detail by both the editors of Coronavirus, Psychoanalysis, and Philosophy, as well as by Rocco Ronchi, an Italian philosopher and one of the contributors to the volume. In his essay ‘The Virtues of the Virus’, Ronchi observes: ‘We are too close to the Covid-19 event to be able to catch a glimpse of the future it bears. Our fear is human, and this makes us unreliable wi tnesses’. Meanwhile, in ‘Introduction: Of Pestilence, Chaos, and Time’, editors Fernando Castrillon and Thomas Marchevsky praise their authors’ boldness for investing in the risky business of writing about the coronavirus pandemic even while ‘knowing full well that they might be ridiculed or even dismissed outright for what at a later date could be read as ill-informed, judgmental, or simply short-sighted’. These are salient warnings for those of us who also wish to make a modest intervention into public debate on the current fast-moving and time-sensitive situation.

tnesses’. Meanwhile, in ‘Introduction: Of Pestilence, Chaos, and Time’, editors Fernando Castrillon and Thomas Marchevsky praise their authors’ boldness for investing in the risky business of writing about the coronavirus pandemic even while ‘knowing full well that they might be ridiculed or even dismissed outright for what at a later date could be read as ill-informed, judgmental, or simply short-sighted’. These are salient warnings for those of us who also wish to make a modest intervention into public debate on the current fast-moving and time-sensitive situation.

It is therefore understandable that Castrillon and Marchevsky choose to provide accurate date-stamps for each of the philosophical and psychoanalytic essays and interviews collected in their book. All but one of the 26 pieces by some of the world’s leading thinkers (including Jean-Luc Nancy, Julia Kristeva, Divya Dwivedi, and Shaj Mohan) were published between February and June 2020, during the ‘suspended existence’ of lockdowns around the globe. Small wonder that some of them are myopic or muddle-headed in a few places, even if the majority speak truths that hold today.

Perhaps the most visionary piece is the excerpt from Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Although this was written as long ago as 1975, Foucault is alert to how disease outbreaks and quarantines go hand in hand with ‘suspended laws, lifted prohibitions, the frenzy of passing time, bodies mingling together without respect, individuals unmasked’. The ongoing relevance of Foucault’s work makes this year’s argument about whether he should be cancelled or not over paedophilia allegations from the two years the philosopher spent in Tunisia during the late 1960s an even more bitter pill.

The book’s absent presence is the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben. Referenced and rebuffed more than any other scholar in the volume, Agamben’s controversial essays about Covid-19 could not be anthologized for copyright reasons. In these essays, which are easily found online, the theorist of bare life and homo sacer argued that the health emergency was being exaggerated or even confected in order to advance governmental states of exception and encroach on civil liberties. This self-serving view of the coronavirus through the lens established in Agamben’s 2005 monograph State of Exception sounded like a call for business as usual in the face of great suffering. In the almost two years that have elapsed since Agamben’s initial essays were published, he has doubled down on his abandonment of the vulnerable by bringing out Where Are We Now? The Epidemic as Politics. In the monograph, Agamben calls SARS-CoV-2 ‘the so-called pandemic’. What’s more, he grandly claims in one parenthetical aside that ‘it’s irrelevant whether it is real or simulated’. Health workers and relatives of the dead around the globe would dispute this glib dismissal. In their different ways, both Agamben and the French gadfly Bernard-Henri Lévy (the author of The Virus in the Age of Madness) speak the eugenicist language of anti-maskers jealously guarding their own privilege as the global death toll continues to rise.

In his riposte to Agamben and other essays from the book, Jean-Luc Nancy is more medically nuanced, recognizing the scale of the threat. In one piece Nancy takes what he says is an Indian neologism, ‘communovirus’, to describe how distancing can be at once a social pursuit and an ethics of care. Read in this light, the temporary state of exception is redolent of a need to ‘live in common’, as Roberto Esposito puts it in the collection’s fifteenth essay, entitled ‘Vitam Instituere’.

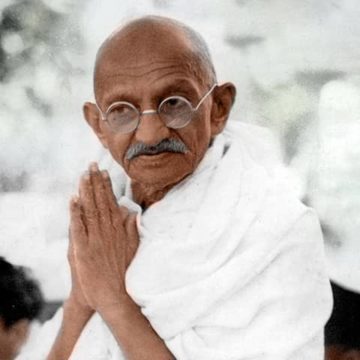

From India itself, Shaj Mohan’s essay ‘What Carries Us On’ opens with the question, ‘for what must we carry on?’ This tacitly recalls Samuel Beckett’s resigned oxymoron, ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on’. Yet before long, Mohan has vaulted from European absurdism to unpicking M. K. Gandhi’s casteist ideas. ‘Gandhi’s idyll’, Mohan claims, ‘is the village of the privileged upper-caste Indian under whom the racial hierarchies and exploitation of the majority lower-caste people carry on, but without an ounce of resentment on the part of the exploited’. From this angle, the stoicism of keeping calm and carrying on functions to conceal inequality. In another essay Mohan wrote with Divya Dwivedi in response to Agamben and Nancy, the pair position high-caste Brahmins as living in a state of exception, occupying rarefied places and not bound by the usual rules. Writing as I do from a Britain roiled by ‘partygate’, the revelation that our political Brahmins have been issuing directives for the masses to isolate even as they flouted those self-same laws, this notion of elitist exceptionalism rings sombre bells.

From India itself, Shaj Mohan’s essay ‘What Carries Us On’ opens with the question, ‘for what must we carry on?’ This tacitly recalls Samuel Beckett’s resigned oxymoron, ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on’. Yet before long, Mohan has vaulted from European absurdism to unpicking M. K. Gandhi’s casteist ideas. ‘Gandhi’s idyll’, Mohan claims, ‘is the village of the privileged upper-caste Indian under whom the racial hierarchies and exploitation of the majority lower-caste people carry on, but without an ounce of resentment on the part of the exploited’. From this angle, the stoicism of keeping calm and carrying on functions to conceal inequality. In another essay Mohan wrote with Divya Dwivedi in response to Agamben and Nancy, the pair position high-caste Brahmins as living in a state of exception, occupying rarefied places and not bound by the usual rules. Writing as I do from a Britain roiled by ‘partygate’, the revelation that our political Brahmins have been issuing directives for the masses to isolate even as they flouted those self-same laws, this notion of elitist exceptionalism rings sombre bells.

In ‘The Return of Antigone’, Argentinian philosopher Néstor Braunstein draws attention to the salience of Sophocles’ play during successive waves of Covid-19 contagion. (A few years earlier Kamila Shamsie had done something similar, showing the classic’s ongoing resonance amid the War on Terror scandal of citizens being made unBritish in her 2017 novel Home Fire.) In the collective trauma of people neither being able to be with their loved ones as they die and nor to attend their funerals in quarantine situations, many South Asians have thought back to the traumatic reference point of Partition, Europeans to the Second World War, and Americans to 9/11. Braunstein writes of bodies thrown in anonymous heaps, a dirty secret like ‘the plastic islands that contaminate oceans’. But unlike Agamben, Braunstein is not so reckless as to deny the need for hygiene and distancing amid the coronavirus emergency. He concludes his essay on a note of pessimism, writing that while the pandemic only exacerbated problems rather than creating them, things will nonetheless be worse than before. One of the reasons for his despair is that for modern-day Antigones unable to bury their brothers, ‘the technology we all use fulfills its pharmacological function: it is both cure and poison’. A memorial for a lost loved one by Zoom cannot stand in for the importance of human touch at a funeral, and the whole volume has much to say about screens and loneliness.

To conclude, even if the noses of these philosophers and psychoanalysts are pressed up against the screen of history, most of their essays continue to reverberate almost two years later. The hope they proffer of a communovirus is worth striving for, even while they are realistic about Covid-19 opening up existing divides and turning them into chasms.