Carolyn Wilke in Smithsonian:

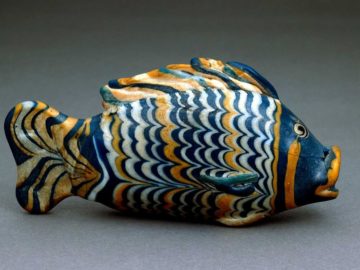

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a decorative writing palette and two blue-hued headrests made of solid glass that may once have supported the head of sleeping royals. His funerary mask sports blue glass inlays that alternate with gold to frame the king’s face.

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a decorative writing palette and two blue-hued headrests made of solid glass that may once have supported the head of sleeping royals. His funerary mask sports blue glass inlays that alternate with gold to frame the king’s face.

In a world filled with the buff, brown and sand hues of more utilitarian Late Bronze Age materials, glass — saturated with blue, purple, turquoise, yellow, red and white — would have afforded the most striking colors other than gemstones, says Andrew Shortland, an archaeological scientist at Cranfield University in Shrivenham, England. In a hierarchy of materials, glass would have sat slightly beneath silver and gold and would have been valued as much as precious stones were. But many questions remain about the prized material. Where was glass first fashioned? How was it worked and colored, and passed around the ancient world? Though much is still mysterious, in the last few decades materials science techniques and a reanalysis of artifacts excavated in the past have begun to fill in details.