Clare Bucknell in The New Yorker:

Oscar Wilde was in the dock when he observed himself becoming two people. It was a Saturday in May, 1895, the final day of his trial for “gross indecency,” and the solicitor general, Frank Lockwood, was in the midst of a closing address for the prosecution. His catalogue of accusations, shot through with moral disgust, struck Wilde as an “appalling denunciation”—“like a thing out of Tacitus, like a passage in Dante,” as he wrote two years later. He was “sickened with horror” at what he heard. But the sensation was short-lived: “Suddenly it occurred to me, How splendid it would be, if I was saying all this about myself. I saw then at once that what is said of a man is nothing. The point is, who says it.” At the critical moment, he was able to transform the drama in his imagination by taking both roles, substituting the real Lockwood with an alternative Wilde, one who could control the courtroom and its narrative.

Oscar Wilde was in the dock when he observed himself becoming two people. It was a Saturday in May, 1895, the final day of his trial for “gross indecency,” and the solicitor general, Frank Lockwood, was in the midst of a closing address for the prosecution. His catalogue of accusations, shot through with moral disgust, struck Wilde as an “appalling denunciation”—“like a thing out of Tacitus, like a passage in Dante,” as he wrote two years later. He was “sickened with horror” at what he heard. But the sensation was short-lived: “Suddenly it occurred to me, How splendid it would be, if I was saying all this about myself. I saw then at once that what is said of a man is nothing. The point is, who says it.” At the critical moment, he was able to transform the drama in his imagination by taking both roles, substituting the real Lockwood with an alternative Wilde, one who could control the courtroom and its narrative.

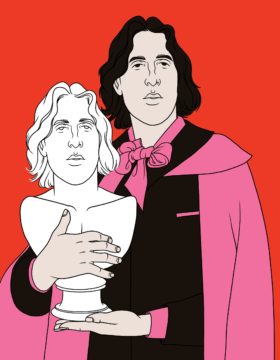

Martyrs don’t usually admit to feeling “sickened” by accounts of their own behavior, and any ambiguities or contradictions in their personalities tend to be glossed over by their hagiographers. Among Wilde’s modern biographers, faced with a subject whose life has been flattened out for exemplary purposes by various communities (gay, Irish, Catholic, socialist), it’s axiomatic to acknowledge his multidimensionality, his slipperiness. “Oscar Wilde lived more lives than one, and no single biography can ever compass his rich and extraordinary life,” Neil McKenna tells us at the beginning of “The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde” (2005), before choosing just one of those lives to tell—Wilde’s sexual and emotional history. Biographers who do aim to “compass” the whole story, as Hesketh Pearson (1946), H. Montgomery Hyde (1975), Richard Ellmann (1988), and now Matthew Sturgis have sought to do, are obliged not only to recognize the many Wildes but to do something about them.

More here.