by Rafaël Newman

Fatherhood and motherhood are always a compromise between a form of Nazi eugenics and a compulsion for repetition. —Paul B. Preciado

If it were up to certain contemporary authors, the title of arch-villain—or rather, Worst Person Ever—might go collectively to a particular category of human normally held up as a model of nurturance and care: viz, to anyone who has willingly and consciously engaged in the act of procreation, whether by “traditional” means, or with scientific assistance. Sally Rooney and Ottessa Moshfegh have written very different, equally angry indictments of parents, while those who appear in the works of Jenny Erpenbeck and Deborah Feldman give the Grimm Brothers a run for their money. And Paul B. Preciado, the gender theorist of my epigraph, is joined in his radically downbeat appraisal of human reproduction by Junot Diaz, who has accused dating apps like Tinder of propagating a species of selective racist breeding.

The convention of decrying rather than celebrating parenthood, of course, did not first arise with the Millennials, or even Generation X. In 1818, Mary Shelley chose as the epigraph to Frankenstein Adam’s surly question to God in Paradise Lost (1667):

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me man? Did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?

—a complaint that places culpability for the travails of life squarely on the shoulders of progenitors, who carelessly indulge their arbitrary, self-centered whims (or allow free rein to their rampant libidos) at the expense of hapless future generations.

Italo Calvino, in a searing response to a colleague of anti-abortion convictions, puts the case succinctly, at least when it comes to the more thoughtless of breeders:

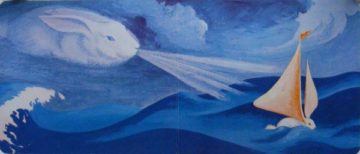

Bringing a child into the world makes sense only if this child is wanted consciously and freely by its two parents. If it is not, then it is simply animal and criminal behavior. A human being becomes human not through the casual convergence of certain biological conditions, but through an act of will and love on the part of other people. If this is not the case, then humanity becomes—as it is already to a large extent—no more than a rabbit-warren.1

Quentin Crisp is more ornate, if no less condemnatory, in the horror scenario he conjures up, David Lynch-like, of the underworld festering beneath the standard nuclear utopia:

If Mr. Vincent Price were to be co-starred with Miss Bette Davis in a story by Mr. Edgar Allan Poe directed by Mr. Roger Corman, it could not fully express the pent-up violence and depravity of a single day in the life of the average family.2

Miscreant parents, meanwhile, when accused of having been motivated by egocentrism, or even sadism, in their family planning, have resorted in turn to accusing their “hideous progeny” (Shelley’s own words, albeit referring to her novel) of ingratitude and disobedience. Or, like Victor Frankenstein, as well as his air-brushed counterpart, the indefatigable mother in Margaret Wise Brown’s Runaway Bunny, they pursue the luckless, shape-shifting creatures of their own invention, in eternal guilt-tripping vengeance for the crime of growing up. But who could blame these monsters, and these bunny rabbits, so many guinea pigs, for fleeing the laboratory?

For an infant human, after all, is the product of a DIY home science experiment for which absolutely no training or authorization is required (indeed, forces are at work in various parts of the world, including “the greatest nation on earth”, to curtail or even abolish basic sex education and birth control). That infant, once born, is in the best case subject to the commandment to repay its makers with love, or at least obedience (AKA “respect,” which, as George Carlin memorably noted, must in fact be earned, and cannot be ordained); in the worst case, said infant may suffer neglect or abuse, in a variety of forms, at the hands of those makers. If the former case obtains, and the infant responds to the affection and support shown it with obedience, respect, or indeed love, it will eventually, when matured to adulthood, be faced with the dwindling and death of its parents, and corresponding pangs of loss, perhaps even guilt; and, if the worst case obtains…well, it’s the worst case. Repeat billions of times, and you get “the universe reproducing itself through us”. Repeat billions of times, and you get quasi-psychopathic, serial abjection on a mass scale. Repeat billions of times, and you get billions of Worst People Ever, people who have failed to heed Philip Larkin’s Sophoclean advice, in his most infamous poem:

This Be The Verse

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

*

The occasion for these morose reflections was my recent return from a holiday spent confronting my own dual role in the cycle of generation, as the middle-aged son of aging parents, and as the middle-aged father of a young adult daughter, all of us bound on our inexorable trajectories, growing up and moving on—to a variety of destinations, some more interim than others. Within the space of two weeks, I had been movingly occupied at either end of the parent-child spectrum: I had visited my 86-year-old, ailing, quasi-eremite father in the viager flat he now “shares”, more or less willingly, in a Montreal low-rise tenement with a procession of care workers; and I had installed my 20-year-old second-born in the all-mod-cons 15th-floor apartment she will be occupying during her third—but first “physical” —year studying at the University of Toronto.

The latter process, which was all about IKEA deliveries and cell phone plans and was attended by boisterous encounters with other members of my generation and of my daughter’s, as well as with my still quite hardy, socially well-integrated mother, was a decidedly cheerier affair than the former, overshadowed as that had been by plans for my father’s increasingly intrusive support, and his understandable resistance to incursions on his autarky. While my daughter was gradually imbibing ever headier draughts of liberty, in other words, my father was witnessing the steady diminishment of his own supply. And I, between them, was experiencing various forms of bereavement, both figurative and literal; both current and proleptic; both vicarious and on my own behalf. I also found myself athwart the fault line that runs directly through my identity: as child and parent in one, I am heir to the same lugubrious burden of inevitable loss (and potential, if unintended, psychological abuse) that I am passing on to my own heirs, a burden whose weight and gravitational pull I am currently and keenly feeling in both directions.

Now, as my father is fond of saying, in a wry inversion of the platitude: “God gave us shoulders—but he also gave us burdens.” (A fatalistic version of the principle that “The work expands to fill the space available.”) It’s a habit, and an attitude, he may have absorbed from his mother, whose first language was not English and who was thus given to a species of idiomatic malapropism: when faced with a reversal of fortune, for instance, she would sigh stoically and remark, “You have to take the good with the bad,” as if life were essentially a bleak darkness into which a weak ray of sunlight had on occasion to be grudgingly admitted (an echo of Yeats’s Irishman, seeing himself through good times with memories of tragedy). But that is very likely how my Bubbi had in fact experienced her life: born in a shtetl in the Czarist Pale, she had been subject to Cossack pogroms and a view of the encroaching Great War from the roof of her family home before being displaced to Canada and a series of harrowing personal and economic challenges. My father remembers her with a fondness, indeed adulation, that increases as her death in 1991 recedes; long ago, however, before her posthumous beatification, my father confided in me that this same mother, who was by her own account depressed during his childhood, would refer to him as a “little Hitler” when he misbehaved, and that this application of a Godwin’s law for parenting had understandably preoccupied him ever since: as had the virtual impossibility of getting a word of love or even praise from his father, who had been cast out of his own immigrant family home as a very young man, to fend for himself in Depression-era Montreal.

Alan Kaufman, whose French-Jewish mother survived the camps and raised him in working-class New York, has written about her episodes of violent rage, and of his own subsequent confusion, in puberty and beyond, of sex and death. My father’s experience of the transmission of pain has certainly been less dramatic; but he has been similarly consumed by thoughts of the Shoah, and by his attempts to escape them in the realm of romantic fantasy; and this radical division in his filial affect has similarly colored his development, as a man and as a writer.

This last is what my father has passed on to me, alongside the standard burden, with the enthusiastic support of my literarily minded mother: a desire to write poetry that repairs and restores, while remaining perilously close to the rift that separates joy from despair, love from abandonment, and truth from death. Like the single aleph that distinguishes the Hebrew word emeth, “truth”, from the word meth, “dead”, and whose inscription, and erasure, on the forehead of the legendary Golem, among the likely forebears of Mary Shelley’s monster, stands for the presence of mortality amid vitality.

My father and I share a recourse to poetry that celebrates the sensuous pleasures of animation even as it recognizes the proximity, and inevitability, of annihilation. During the last of our four hour-long meetings at his home in Montreal last month, meticulously apportioned to allow him the space and time he requires to recover from human interaction, he cited a poem of his, a hallucination or perhaps apocalyptic vision, from Sudden Proclamations, a collection published nearly thirty years ago.

Intimations

A shiver of something quick

goes through us now and then,

as if

the misaligned heart

were about to fracture under bone

or a silent planet

thinned itself

against the dark, unknown.

My father was delighted when I cited along with him from memory, but suggested that the final word, “unknown”, although pathos-drenched enough, yet presupposed the presence of potential knowers, and thus situated the titular visionary in possible company; while replacing it with the similarly rhymed word “alone” would convey a more profound solitude. It was as if we had returned for a moment to the collegial repartee we had once enjoyed, when I was an aspiring poet and he was an active professor of creative writing, producing seasoned verse of his own; and although his poem had long since been published, he indicated on this most recent occasion that he was quite willing to consider a revision.

In return, he recalled one of my own early efforts, a poem I had written when a lovestruck, very young adult; one which he had always admired, and which I had since published in a collection of my own.

Aubade

It was a savage night

Under your duvet:

I think the original principal

Of our convexity

Hunted coelacanth

In the Olduvai Gorge;

I know your body

Was on the loose in mine.

He was reminding me, it seemed, of my own enthusiastic discovery of sodality, and of the pleasures, promises, and comforts of company beyond the family unit. He then asked me whether I was writing anything now, and when I told him that I had not composed much poetry lately, apart from occasional verse, he told me, in the manner of a sudden proclamation, that he expected I would now write something, derived from or inspired by our visit that day, and that I would then present it to him to read. I was grateful that he did not remark, as he had been given to on the occasion of recent partings, that this visit might well be our last; and I resolved to do as he requested: or rather, as he had predicted.

A Noble Jargon

For CJ

A noble jargon joins us to this day,

Which generates our speech: a period

Composed of all the things we always say,

And those we never, which are myriad.

Yours is the root, inflected in the case

Each predicate requires; mine is the verb,

Selected from a matrix whose embrace,

Though I decline, our discourse may disturb.

You gifted me this grammar: but in truth,

It was not yours, or only yours on loan,

Provided in your time you grant my youth

A usufruct as bounded as your own.

Thus are we fluent still in our old tongue,

Which, though we age, we keep forever young.

I was thinking, of course, about the language, and the love of language, that unites us, as well as of the oracular quality of his poem, with its location of a cosmos within the individual self, and the archeological trope of my poem, with its ontogenetic recapitulation of phylogenesis. But I was also hoping to acknowledge his gifts to me, and implicitly express the hope that I have been able to pass them on to my own children, in some form. For alas, I am afraid that my own experience of being parented has been the best case—the inspiration of a filial love, and the inculcation of a respect, for both parents, that will leave me ultimately bereft; but I am also hopeful that I may do the same lachrymose duty by my own offspring, and thus repay forward those heavy, joyful gifts.

______________________________________________

1 Italo Calvino, Letters, 1941-1985, tr. Martin McLaughlin (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013). I am indebted to the excellent Joan Harvey for this reference.

2 Quentin Crisp, Manners from Heaven (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1984).