Matt Davenport in Science:

For decades, scientists suspected that bacteria known as Geobacter could clean up radioactive uranium waste, but it wasn’t clear how the microbes did it.

For decades, scientists suspected that bacteria known as Geobacter could clean up radioactive uranium waste, but it wasn’t clear how the microbes did it.

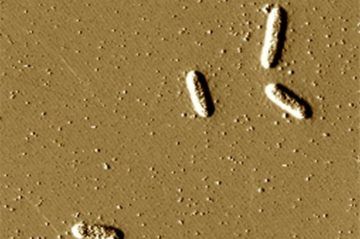

“The biological mechanism of how they were doing this remained elusive for 20 years,” said Gemma Reguera, the Spartan microbiologist whose team solved that mystery 10 years ago. Well, three-quarters of the mystery. She’s now cracked the rest of the case. What Reguera discovered in 2011 was that, on one side of their cells, the Geobacter make protein filaments that act like little wires to literally zap uranium. This does two things. For one, the jolt triggers chemical reactions that give the bacteria energy. Secondly, that chemistry traps the uranium in a mineral form, preventing the radioactive material from spreading through the environment. But those protein wires accounted for just about 75% of the uranium that the Geobacter were cleaning up.

“We always knew we were missing something,” said Reguera, a professor of microbiology and molecular genetics in the College of Natural Science. “What we didn’t know was what was happening at the cell surface, particularly on the side of the cell that had no wires to immobilize the uranium.”

Now, Reguera’s team has the answer. Molecules called lipopolysaccharides coat the cell surface and soak up the uranium like a sponge.

More here.