by Chris Horner

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.

This year marks the 200th anniversary of Napoleon Bonaparte’s death in exile on the island of St Helena. And it was 206 years ago last June that his career came to a bloody end at Waterloo, with defeat at the hands of an allied army led by Britain’s Wellington and Prussia’s Blucher. But while the Emperor himself is dead and gone, the Napoleon Myth marches on, and is celebrated in some unlikely quarters.

The Guardian’s Martin Kettle is a big fan of the Emperor, as is the historian Andrew Roberts. Both have written admiringly on the man, the former in the pages of his newspaper, the latter in a big biography that verges on hagiography. On the face of it this is odd – Kettle is a liberal and Roberts is a conservative. What could they both find in the life of the ‘Disturber of the Peace of Europe’ to admire? They are not first to mourn the fall of Napoleon and sympathise with those who saw him as a great bulwark against reaction, but just the latest in a long line of Bonaparte fans. I’m not inclined share their adoration of the Corsican Adventurer.

It is certainly true that an appalling set of Crowned Heads did well out of the fall of the Emperor: after 1815 they imposed reactionary regimes across the content of Europe, which lasted until at least 1848. And in Britain the period fallowing the wars was one of great suffering and repression, a veritable ‘Thanatocracy’ in which armed force and the noose secured the rule of the rich. It is understandable that any radicals of the day tended to see Napoleon as a great alternative to the tyranny of the Monarchs who fought him: the essayist Hazlitt kept a bust of Napoleon on his desk, Byron publicly regretted the result at Waterloo, and later Victor Hugo devoted a large section of Les Miserables to mourning the fall of the Emperor in 1815. They saw him as carrying the spirit of the great Revolution of 1789 forward, and wished he had prevailed on the field of battle.

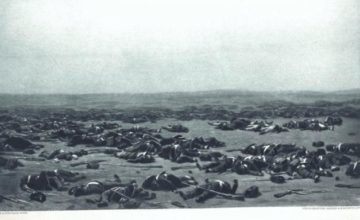

Yet despite their sensible abhorrence of the post 1815 reaction the truth is that Napoleon, too, was a ruthless despot. It is true that some of the advances of the Revolution survived, perhaps thanks to him, but we should not sympathise with a man who sent many hundreds of thousands of soldiers to their doom and caused the deaths of many more civilians in order to secure and extend his reign. We should also remember that he crushed the last embers of democracy in France underfoot in his rise to power. The fact that some good things flowed from him (e.g. the Code Napoleon etc) doesn’t alter that. Millions died, thanks to his activity at the slaughter-bench of history.

Yet despite their sensible abhorrence of the post 1815 reaction the truth is that Napoleon, too, was a ruthless despot. It is true that some of the advances of the Revolution survived, perhaps thanks to him, but we should not sympathise with a man who sent many hundreds of thousands of soldiers to their doom and caused the deaths of many more civilians in order to secure and extend his reign. We should also remember that he crushed the last embers of democracy in France underfoot in his rise to power. The fact that some good things flowed from him (e.g. the Code Napoleon etc) doesn’t alter that. Millions died, thanks to his activity at the slaughter-bench of history.

Some people, like Martin Kettle, may like him because, as right of centre liberals, they see him as a bridge from the ancien regime to modernity, a modern market economy. So Bonaparte is admirable in a way that Robespierre isn’t, although the former eradicated democracy, tried to re-enslave Haitians, eliminated opponents and launched wars of conquest. Still, he didn’t guillotine aristocrats, so that’s alright. As for conservatives like Andrew Roberts, they may have some of the same reasons as types like Kettle (since so much modern conservatism is really just a version of liberalism). There is, though, another reason for this celebration of the Great Man of History.

It is power worship. ‘Strong leaders’ who win a lot are aphrodisiacal to many intellectuals and scribes. This is not confined to the political right or centre: George Orwell commented on the way in which leftish intellectuals in the 1930s and 40s worshipped Stalin – from a safe distance. There is something about the Great Leader who Conquers that attracts some people like flies to jam. And we can surely think of contemporary examples of this kind of thing. While Great Leaders are successful they seem quite marvellous, although sometimes less so a bit later on. Napoleon, though, is a special case, as even after defeat he still earns the obeisance of some historically minded writers.

Napoleon was certainly in a class of his own when it came to winning battles, whether as a general of the Directory, as First Consul or Emperor. But all the battles he won didn’t bring the peace he kept promising his people, in no small part thanks to his hubris. He didn’t know when to stop, and in the end others put a stop to him. The unpleasant nature of his opponents shouldn’t blind us to the fact that he was a monster. It is true that he had ugly, reactionary enemies, but he also killed democrats and genuine revolutionaries in the promotion of his own ‘glory’. It ought to be possible to grasp both facts: my enemy’s enemy is not my friend.

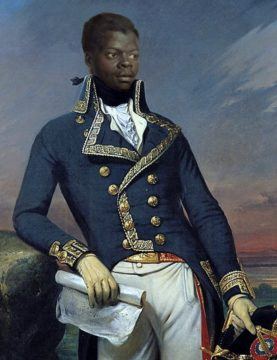

If we must have heroes, let me propose an alternative: Toussaint l’Ouverture, leader of the Haitian revolution, whose betrayal and imprisonment by Napoleon couldn’t reverse the victory of the first great, successful slave rebellion – or rather revolution -in history. He fought not for his own self aggrandisement, but for the freedom of his people. Thanks to people like him, history is more than a mere catalogue of folly and crime.