Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver is no doubt in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “Wynona’s Big Brown Beaver” (1995), that entirely explains this animal’s peculiar symbolic scent. The crude term for a woman’s genitals, “beaver”, itself builds on a long history in which the figure of the animal is held up as a mirror and a speculum of human venery, and also of the transcendence of this condition through virtue.

Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver is no doubt in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “Wynona’s Big Brown Beaver” (1995), that entirely explains this animal’s peculiar symbolic scent. The crude term for a woman’s genitals, “beaver”, itself builds on a long history in which the figure of the animal is held up as a mirror and a speculum of human venery, and also of the transcendence of this condition through virtue.

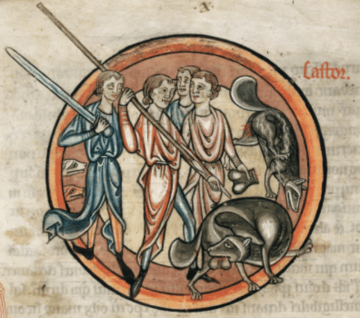

For most of its history the beaver, hunted for its medicinal castoreum, was sooner associated with male testicles, and with the horrible yet paradoxically emboldening prospect of their loss. Later, it was taken up as the very model of the social animal, living in imagined New World dam communities constructed through the ingenious collaborative labor of these hominoid rodents. Beavers, the “busy” American animals, embodied the work ethic so many thought necessary for the transformation of that wild continent.

It is worth considering the extent to which these two images of the beaver —the one focused on its hind parts and their perceived virtues and vices, the other on its industry— are but two chapters of a single continuous history.