Adam Kirsch in The New Yorker:

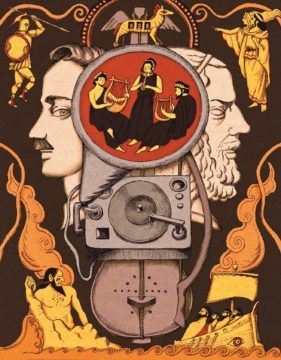

The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in Rembrandt’s 1653 painting “Aristotle with a Bust of Homer.” Whether you stand in front of it at the Metropolitan Museum or look at it online, the painting turns you into a link in a chain that goes back three thousand years. Here you are in the twenty-first century, contemplating a painting made in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century, which portrays a philosopher who lived in Athens in the fourth century B.C., looking at a poet thought to have lived in the eighth century B.C. Tradition abolishes time, making us all contemporaries. Yet the painting hints that Homer doesn’t quite belong in the same dimension of reality occupied by you, Aristotle, and Rembrandt.

The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in Rembrandt’s 1653 painting “Aristotle with a Bust of Homer.” Whether you stand in front of it at the Metropolitan Museum or look at it online, the painting turns you into a link in a chain that goes back three thousand years. Here you are in the twenty-first century, contemplating a painting made in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century, which portrays a philosopher who lived in Athens in the fourth century B.C., looking at a poet thought to have lived in the eighth century B.C. Tradition abolishes time, making us all contemporaries. Yet the painting hints that Homer doesn’t quite belong in the same dimension of reality occupied by you, Aristotle, and Rembrandt.

Aristotle is portrayed realistically in the dress of Rembrandt’s time—sumptuous white shirt, simple black apron, and broad-brimmed hat. (It wasn’t until the twentieth century that art historians determined that the figure was Aristotle; earlier identifications included a contemporary of Rembrandt’s, the writer Pieter Cornelisz Hooft.) In other words, Aristotle is a human being like us, albeit an extraordinary one. Homer, however, is a white marble bust—a work of art within a work of art.

It’s a reminder that, even for Aristotle, Homer was more a legend than a man. In his Poetics, the philosopher credits the poet with inventing epic, drama, and comedy. “It is Homer who has chiefly taught other poets the art of telling lies skillfully,” he writes with evident ambivalence. Herodotus, known as the first historian, saw Homer, along with the poet Hesiod, as having invented Greek mythology, calling them the first to “give the gods their epithets, to allot them their several offices and occupations, and describe their forms.” When it comes to things like when and where Homer lived, however, the earliest sources are already unreliable. According to tradition, the poet was blind and was born on the island of Chios, where a guild of rhapsodes—reciters of epic poetry—later became known as the Homeridae, “children of Homer,” and claimed to be his direct descendants. But there is no evidence for any of these assertions, and some ancient biographies of Homer are obviously fanciful.

Herodotus writes that Homer lived “four hundred years before my time,” which would put him in the ninth century B.C., but adds that this is “my own opinion,” with no real proof behind it.

More here.