George Scialabba in The Baffler:

George Scialabba in The Baffler:

AT THE END OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, the United States, with 6 percent of the world’s population, accounted for 50 percent of the world’s production. Militarily, it was invulnerable: it controlled both oceans and had sole possession of the most fearsome weapon ever invented. Culturally, American movies and popular music were all-conquering. Perhaps most important was America’s moral standing. Woodrow Wilson’s (not entirely deserved) reputation as an apostle of self-determination; the United States’ apparent lack of territorial ambition; and the awful fate from which the U.S. and the USSR had saved Europe—all aroused hopes for America’s moral leadership. Those hopes seemed to find fulfillment in the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as wise and generous a scheme for international order as any yet devised. But the UN, along with America’s moral prestige, fell victim to the superpower rivalry that extended from 1945 to 1991 and is known as the Cold War.

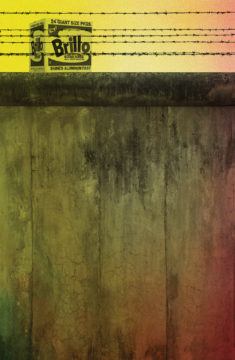

That is not the story Louis Menand aims to tell in his teeming and colorful history of “art and thought in the Cold War.” Helpfully, Menand explains that this is “not a book about the ‘cultural Cold War’ (the use of cultural diplomacy as an instrument of foreign policy).” Nor is it a book about “‘Cold War culture’ (art and ideas as reflections of Cold War ideology and conditions).” (A good example of the former is Frances Stonor Saunders’s The Cultural Cold War; of the latter, Duncan White’s Cold Warriors.) The Free World is intellectual history, primarily a narrative of ideas talking to ideas and works of art talking to works of art, while also trying to take into account “the underlying social forces—economic, geopolitical, demographic, technological—that created the conditions for the possibility of certain kinds of art and ideas.”

More here.