Stuart Newman in Counterpunch:

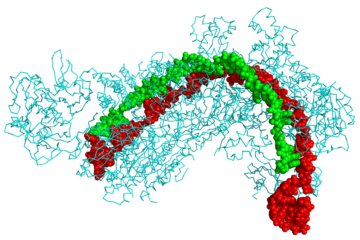

The Nobel prize in chemistry awarded last year to the biochemists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for the genetic modification technique called CRISPR cemented the popular idea that a new era of precision manipulation of hereditary material had arrived. The award came on the heels of the unauthorized use of the technique by the scientist He Jiankui in 2018 in China in an effort to produce individuals (twin girls in this case) resistant to HIV, and a flurry of studies in early 2020 showing that accuracy in altering DNA in a test tube or bacteria in a culture dish, did not hold up when applied to animal embryos. Attempts to modify single genes in human embryos (not intended to be brought to full-term) in fact led to “large-scale, unintended DNA deletions and rearrangements in the areas surrounding the targeted sequence,” aka “genetic chaos.”

The Nobel prize in chemistry awarded last year to the biochemists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for the genetic modification technique called CRISPR cemented the popular idea that a new era of precision manipulation of hereditary material had arrived. The award came on the heels of the unauthorized use of the technique by the scientist He Jiankui in 2018 in China in an effort to produce individuals (twin girls in this case) resistant to HIV, and a flurry of studies in early 2020 showing that accuracy in altering DNA in a test tube or bacteria in a culture dish, did not hold up when applied to animal embryos. Attempts to modify single genes in human embryos (not intended to be brought to full-term) in fact led to “large-scale, unintended DNA deletions and rearrangements in the areas surrounding the targeted sequence,” aka “genetic chaos.”

Dr. He was imprisoned, fined, and fired from his academic position in China for his actions, although it is still not clear to what extent the higher-ups at his institute were aware of it. At a small meeting that I attended in Berkeley in early 2017 where He spoke, he unambiguously stated that “these things are thought of differently in China than in the U.S.” The U.S. scientific establishment uniformly condemned He’s experiments, but when questioned, most scientists, including Doudna herself, and bioethicists (a profession dedicated, with a few exceptions, to getting the public used to what the scientists and bioentrepreneurs have is store for them), left the door open to future manipulation of humans.

In a recent review in the New York Review of Books of four books on the prospects of using CRISPR and related gene modification technologies for the improvement of human biology (“Editing Humanity’s Future”; April 29), including Walter Isaacson’s paean to Jennifer Doudna, the biotechnology editor and writer Natalie de Souza addresses the safety of such manipulations as a fundamental requirement for moving forward with human applications. But de Souza, in common with the authors of all the books under review, downplays the fact that “safety” means entirely different things when therapeutic alterations of the tissues of a mature body are considered, in contrast to those that are administered at early embryonic stages. The engineering of retinal cells to relieve blindness, for example, a promising, although still uncertain, application of the technique, is not comparable to ridding embryos of genes associated with cystic fibrosis, HIV susceptibility, or sickle cell disease.

More here.