Christian Lorentzen in Bookforum:

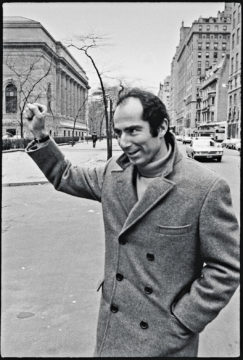

When Roth died at age eighty-five in 2018, Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times that it was the end of a cultural era. Roth was “the last front-rank survivor of a generation of fecund and authoritative and, yes, white and male novelists.” Never mind that at least four other major American novelists born in the 1930s—DeLillo, McCarthy, Morrison, Pynchon—were still alive. Forget about pigeonholing as white and male an author who at the beginning of his career was invited to sit beside Ralph Ellison on panels about “minority writing”—because Jews were still at the margins. No matter that the modes that sustained Roth—autobiography with comic exaggeration, autobiographical metafiction, historical fiction of the recent past—are the modes that define the current moment. Roth was not an end point but the beginning of the present. There had been fluke golden boys before him, like Fitzgerald and Mailer, but Roth, twenty-six when he won the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus in 1960, reset the template for the prodigy author in the age of television, going at it with Mike Wallace in prime time. The morning before he spoke to Wallace he gave an interview to a young reporter for the New York Post, who asked him about a critic who’d called his book “an exhibition of Jewish self-hate.” A few weeks later the piece turned up in the mail Roth received from his clipping service while he was staying in Rome. He was quoted as saying the critic ought to “write a book about why he hates me. It might give insights into me and him, too.” “I decided then and there,” his biographer Blake Bailey quotes him saying at the time, “to give up a public career.”

When Roth died at age eighty-five in 2018, Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times that it was the end of a cultural era. Roth was “the last front-rank survivor of a generation of fecund and authoritative and, yes, white and male novelists.” Never mind that at least four other major American novelists born in the 1930s—DeLillo, McCarthy, Morrison, Pynchon—were still alive. Forget about pigeonholing as white and male an author who at the beginning of his career was invited to sit beside Ralph Ellison on panels about “minority writing”—because Jews were still at the margins. No matter that the modes that sustained Roth—autobiography with comic exaggeration, autobiographical metafiction, historical fiction of the recent past—are the modes that define the current moment. Roth was not an end point but the beginning of the present. There had been fluke golden boys before him, like Fitzgerald and Mailer, but Roth, twenty-six when he won the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus in 1960, reset the template for the prodigy author in the age of television, going at it with Mike Wallace in prime time. The morning before he spoke to Wallace he gave an interview to a young reporter for the New York Post, who asked him about a critic who’d called his book “an exhibition of Jewish self-hate.” A few weeks later the piece turned up in the mail Roth received from his clipping service while he was staying in Rome. He was quoted as saying the critic ought to “write a book about why he hates me. It might give insights into me and him, too.” “I decided then and there,” his biographer Blake Bailey quotes him saying at the time, “to give up a public career.”

At the time the remark might have been wishful thinking. In retrospect it’s laughably disingenuous. Far from retreating from public view, Roth embarked on a decades-long campaign of public-image control. He always hated critics, but reserved his vitriol for lengthy letters to the editor (one to the New York Review of Books in 1974 suggested that Times staff critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt be sacked and his job be filled by an annual contest among undergraduates) or fictionalized rebukes where he and his alter-egos had the last word.

More here.