by Varun Gauri

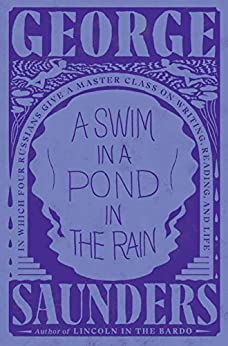

In his recent book A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, George Saunders offers insights into writing good short stories. I may consider his craft advice in another context; here, I want to explore the book’s implications for bad stories and, specifically, the bad stories we call public narratives.

Saunders contends that “we might think of the story as a system for the transfer of energy.” This comes in a discussion of Chekhov’s “In the Cart,” in which a description of Marya, an unhappy, lonely school teacher, creates an expectation for the reader that Marya must necessarily endeavor to become less unhappy, less lonely, as the story unfolds. That’s the energy transfer — an observation at one point in time creates heightened attention, and specific expectations that are the springboard for action, later on.

Public narratives are similar. When we say America is “the land of free,” we not only evoke, implicitly or explicitly, the stories of the American Revolution and the liberation of people under the Axis powers, but create specific expectations that America will later fulfill or fail. Robert Shiller, in Narrative Economics, makes a similar point: “If we want to understand people’s actions . . . we need to study the “terms and images that energize” (Shiller is quoting the historian Ramsay MacMullen). Authoritarian societies provide many examples of the energetic function of public narratives; for example, a statement that the Aryans were the master race was not only an historical claim but an exhortation to make it true, by dominating and destroying other races.

Edward Luce argues that public narratives connect a population’s greatest fears with its highest hopes:

The secret to any nation’s diplomatic character is embedded in its popular imagination. If asked which historic events made them proudest, most British would choose the darkest days of the Second World War, when Britain faced Nazi Germany alone. Many would also mention the defeat of the Spanish Armada in the reign of Elizabeth I, or victory over Napoleon. Britain’s worst fears, and deepest triumphs, have always coincided with Europe’s unification under one power. The past is never really dead. It is not even past. The 2016 Brexit vote was today’s version of Henry VIII’s break with Rome.

Luce further notes that primary Chinese narratives connect national self-respect and dignity to the fear of succumbing to foreign powers: Celebrated moments in the Chinese popular imagination are the detonation of the hydrogen bomb in 1964, and Britain’s transfer of Hong Kong in 1997, ending a century of humiliation. Regarding India, Susan and Lloyd Rudolph argue that Gandhi’s efforts to recast Hindu vegetarianism and asceticism in masculine terms, through fasts and strong-willed campaigns of non-violence, repaired “wounds in self-esteem and potency, recruiting and mobilizing new constituencies and leaders, helping India to acquire national coherence.”

In these examples, public narratives marshal energies, and set specific expectations, in order to spur action to overcome national anxieties, whether the threats from a unified Europe in Britain’s case, humiliation at the hands of foreign powers in China, or personal and national disorder in India. I want to claim that a function of public narratives, generally, is to keep fears at bay; that is what makes them bad stories.

In the Chekhov story, Marya’s wagon passes a rich, handsome landowner who, for a moment, we think will be the answer to her loneliness. No such luck. A simple resolution like that to Marya’s loneliness would, Saunders says, amount to “ritual banality,” or a “crappo” story. Chekhov instead takes Marya into a peasant teahouse, where we learn she is nearly a peasant herself; then, in the climax, a train platform evokes a glorious memory of Marya’s mother and father, their lovely Moscow apartment, her aquarium with little fishes, the piano playing. It is the first time in thirteen years Marya has thought of her previous, happy life, and her dead family members; it seems this woman’s loneliness can be relieved only in memory, which is to say never at all, or only in a way that deepens it. Good short stories lean in; they explore the characters’ fears, rather than resolving them too soon.

A married woman, upset with domesticity and her husband’s family’s casual aggressions, stops eating and starts losing weight. Sad, right? If we met her in life, we might tell her to be kind to herself; maybe she should try yoga or go into therapy. What is incredible about Han Kang’s The Vegetarian is that the story refuses, doesn’t even glance at, the ritually banal answers. Instead, we watch as the woman’s revulsion at human aggression passes into vegetarianism, self-harm, nudity, plant-like passivity, and institutionalization; her anger, directed inward, encompasses the discontents of civilization. Good stories gaze directly; they avoid the most common real-life responses — averting the eyes, avoiding the anxieties, banality and the crappo impulses.

In contrast, public narratives depend, for the power, on looking away. They typically refuse to name the fears they are concerned with, though of course the lurking presence of the fears creates the expectations that energize: America has universal values (never mind the slaves); Britain enjoys splendid isolation (leaving so few men, so happy few. supposedly); China is an ancient, unified civilization (forget the Opium Wars).

As Reed Berkowtiz notes, QAnon gamifies public narratives. Players solve riddles, put together clues, and come to conclusions about esoteric, strange phenomena that the mainstream media are allegedly too lame or corrupted to examine. This is storytelling and story creating: “the purpose of Q is not to divulge actual information, but to create fiction.” QAnon fictions enact energy transfers from fears regarding the soundness or integrity of public institutions to swarm-like social action. QAnon is extreme, relying not just on fear but outright paranoia, but it bears a relationship to public narratives more generally.

The economic narratives Shiller discusses also draw on fears. Consider his examples of bank runs and panics, the automation of jobs and the coming of the robots, and real estate bubbles — savings account holders fear being left holding the bag, investors don’t want to miss out on a big bull market, and workers fear looming unemployment and meaninglessness. Whereas the fear of domination drives political narratives, these economic narratives tend to involve the fear of being left out, or missing out from, pecuniary returns (financial FOMO).

Shiller believes “economists can best advance their science by developing and incorporating into it the art of narrative economics.” In other words, understanding public narratives could help economists make better predictions about business cycles, wage negotiations, asset prices, and other economic variables. Maybe so. But Shiller’s understanding of narrative economics is wide, encompassing not only narratives in the sense I’m discussing (representations of event sequences transferring emotional energy over time) but also more or less formal economic models, social norms, causal arguments, zombie ideas, motivated reasoning, framing, and processes that select for emotionally charged memories.

The essay I’m writing is an exercise in hypothesis generation. If the claim is correct — if public narratives are bad stories about fears — then it might be possible, if one were pursuing Shiller’s goals, to use text scraping techniques to measure levels of, and changes in, fear in the narratives of relevant actors, and use those results in the right hand side of economic models.

In addition, if the claim isn’t completely off base, it raises the question of whether public narratives are necessarily bad stories, or if it’s possible for them to be made more subtle, or refined, in ways that encourage the use of their energies in more self-consciously constructive and creative ways. I really don’t know, but I suspect that group identities may be strongly connected to fears and security concerns. Maybe the best we can hope for is to become better readers of good stories, so that we are able to resist bad stories more effectively, as Saunders notes:

The part of the mind that reads a story is also the part that reads the world; it can deceive us, but it can also be trained to accuracy; it can fall into disuse and make us more susceptible to lazy, violent, materialistic forces, but it can also be urged back to life, transforming us into more active, curious, alert readers of reality.